The Real History of the Ballista, Game of Thrones' Anti-Dragon Weapon

Warning: Spoilers!

Cersei Lannister needs some anti-dragon air defenses, so the twisted mind of Qyburn has dreamed up a double-bowed monstrosity. In season 7, he tests it on an ancient dragon skull (which would be like firing an AR-15 through King Tut's sarcophagus), and in season 8-it appears he's made even more.

But Cersei's high powered anti-dragon weapon is much more than just fantasy. In human history, this old-school Godzilla-sized crossbow goes by a different name-a ballista.

This kind of catapult uses a pair of bent bow springs to store and release energy. Sure, it works well enough to put a big hole in a dragon, but there's no getting around the fact that it's 2,500-year-old technology. In fact, Qyburn's engineering solution closely resembles the very first pieces of artillery ever made on Earth.

This kind of ballista dates back to 399 BCE, when King Dionysius of Syracuse besieged a walled town called Motya located on the island of Sicily. It was a long and bitter siege, and the Syracuseans brought their ships very close to the town walls, drawing them up on the beaches outside the town. According to the Greek historian Diodorus, the Motyans counterattacked, but something kept them at bay.

"[The Motyans] were held back by a great quantity of flying missiles. The Syracuseans slew many of the enemy by using from the land the catapults which shot sharp pointed missiles. Indeed, this weapon caused great dismay, because it was a new invention at the time."

Dionysius' original machines were pretty much oversized bows and arrows, using a really big bow fabricated from wood and animal parts like horns and cartilage, very similar to Qyburn's catapult.

The Syracusean devices worked reasonably well, but they had a lot of problems. First, they were not particularly powerful. Wooden bows can only get so powerful before they get too big to move. It's asking a lot of bow-powered machines to shoot through anything really thick. Second, they are heavy. Ballistae take a lot of manpower to wrestle them into firing position. If the target is moving, you're pretty much screwed. But the biggest problem with these early ballistae was that they were excruciatingly slow to use. Loading a dart, winching back the bows, and taking aim means a lousy rate of fire.

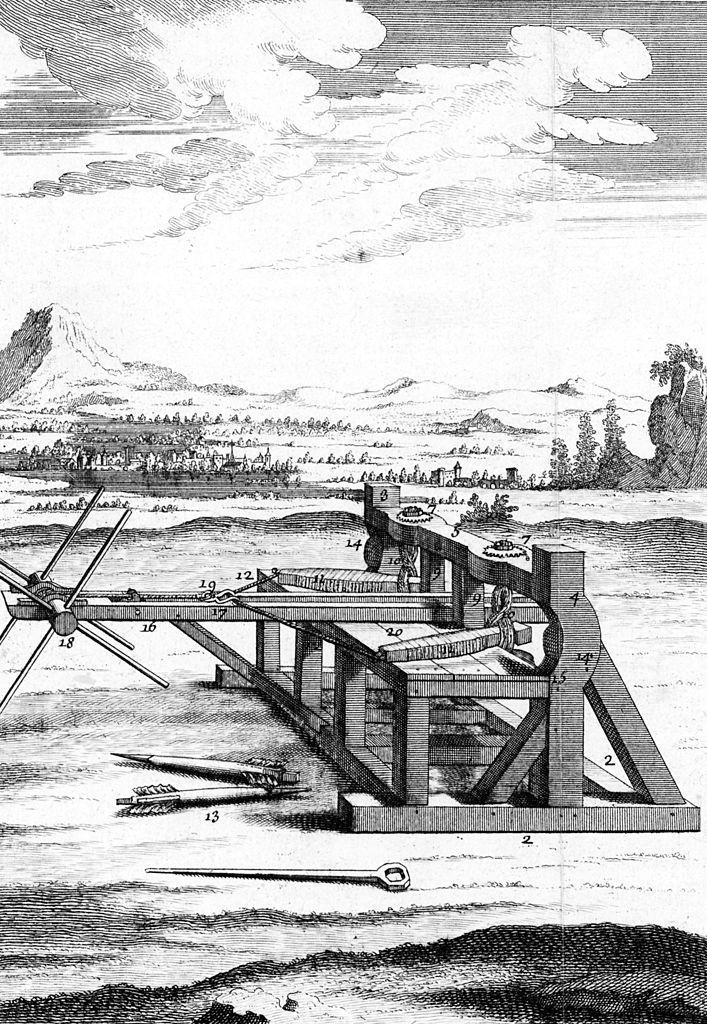

It wouldn't be until 332 BCE, in the hands of Alexander the Great's catapult engineers, that the ballista would be perfected. Realizing that these big-ass bows had reached their limit in both distance and power, they came up with a new idea. Instead of a bent bow, why not use springs made from tightly strung coils of rope? When you fix the ends of a rope loop and then twist it, the coiling rope resists the rotation and pushes back in the opposite direction. So, if you made a bundle of big, strong, tightly strung rope coils, they could store and then release a lot of energy. The tighter the coil, the bigger the projectile.

Once completed, these engineers named their new creation a "ballista." They used two vertical bundles of rope made from hair or animal tendons that were strung tight like the strings on a tennis racket. Wooden throwing arms were inserted between the two rope bundles that made up the catapult spring. When it was used on the battlefield, the artillery men working the machines winched back the arms, inserted a stone or metal-tipped dart, and released the trigger. With a great snap, the rope spring uncoiled, releasing its deadly energy.

The weapon eventually became of mainstay of the Roman Empire, but after its collapse, many resulting kingdoms lacked the means for its upkeep. However, it still found its way into decisive battles with the possibility of changing the course of human history. Ballistae were usually fired against stationary items such as castle walls or gates-not exactly something as mobile as a flying dragon the size of airliner. But on rare occasion, they were used as antipersonnel weapons.

In 885, for example, a Viking horde under the leadership of Rollo sailed up the river Seine and attempted to invade Paris. As the story goes, a mere 200 French soldiers withstood the siege of 30,000 Danes for nearly a year, forcing the attackers to give up and bypass the city. Notably in that siege is the eyewitness account of the French monk, Abbo Cernuusdescribing the use of ballistae by the French leader, King Odo, in his poem Wars of the City of Paris.

Arrows flew here, there through the air; blood gushed and flowed; Darts, stones, and javelins were hurled by ballistae and slingshots. Nothing was seen, between heaven and earth but these projectiles.

Abbo's account, originally written in Latin, goes on to describe how one particularly skilled ballista user named Ebolus used his machine successfully against the attacking Vikings, and then makes a colorful joke about the incident:

With a single spear, he skewered seven Danes all at once; And in jest he said to his men to take them to the kitchen.

With the advent of other medieval siege weapons, like the smaller ballista called a Springald, the more precise crossbow, and mostnotably the trebuchet, ballistae eventually fell into obscurity, but it never disappeared completely. In our real world you'll likely only find these ancient weapons faithfully recreated in a museum, maybe a few time-worn parts if you're lucky, but Game of Thrones and other fantasy fiction (whether 100 percent accurate or not) appears dedicated to preserving the memory of this deadly weapon's 1,700-year reign.

This post was originally published in 2017, it's been updated for Games of Thrones Season 8.

('You Might Also Like',)