Rail tickets: A ridiculous state of fares?

The gentleman on the other side of the aisle on the 7.55pm from Manchester to London last Thursday paid up quietly; he had been correctly and politely surcharged by the train manager for failing to show his railcard.

But once the diligent Virgin Trains official moved on, the unhappy passenger launched into a tirade about rail fares.

“It’s the thing that annoys me the most about the UK,” he grumbled to his companion. “Trains should be a public service. German train fares are so much more reasonable.”

To interject with a contrary view might not be wise, I judged, given the long line of empty lager cans in front of him. So instead I listened in to his rage against the machinery of rail fares.

“When I have a morning meeting in Manchester it costs a fortune. Why is it £160 for a one-way ticket? Why does it have to be that much?”

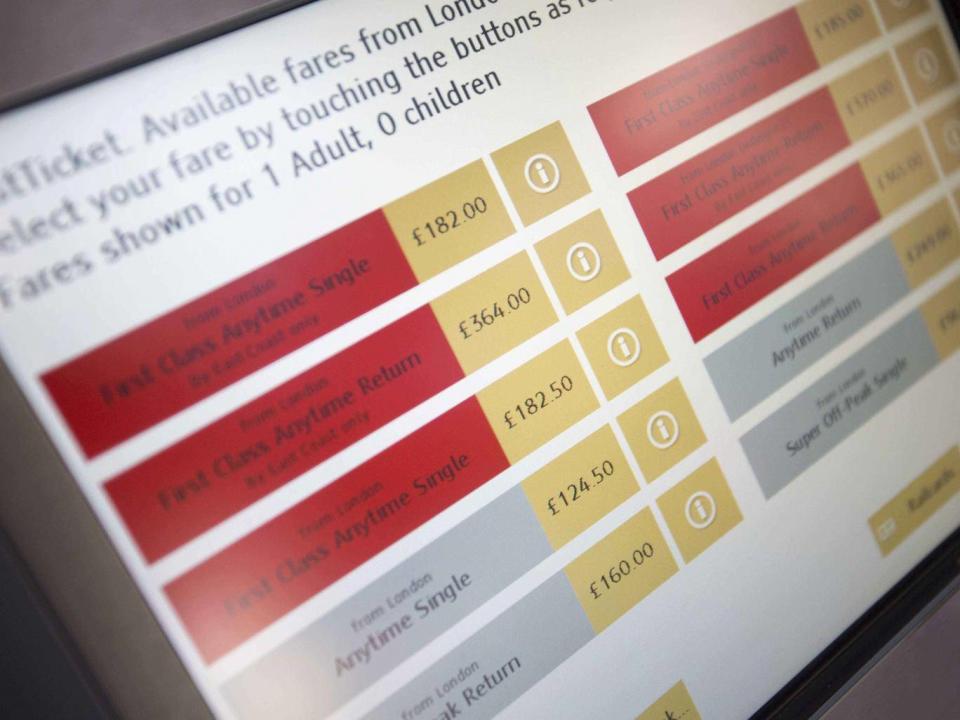

In fact, he had understated the cost of an Anytime single from London Euston to Manchester. Anyone with the temerity to leave the capital before 9.30am and who buys a “walk-up” ticket will pay £169. And from the first working day of 2019, it could rise to £175 – approaching £1 per mile, and feeling more like an on-the-spot fine than a rail ticket for a two-hour journey.

Every year, the rail industry gets a triple kicking over train fares.

In August, the retail price index for the previous month is announced. While this measure of inflation has long been discredited for exaggerating price rises, successive governments have doggedly locked rail tickets to RPI. “Regulated” rail fares – season tickets in the London area, Anytime tickets around major cities and many off-peak return tickets on long distance journeys – will rise by 3.2 per cent, except in Scotland where increases are capped at RPI minus 1 per cent. Other “walk-up” prices, such as that ferocious London-Manchester fare, typically rise by the same amount.

Kicking 2 happens shortly before Christmas, when train operators reveal the exact new fares. Constituents of the transport secretary, Chris Grayling, who commute from Epsom to London, are likely to see their annual season ticket rise by £65 to £2,105. The travelling public traditionally responds with fury.

And on the day when the new fares take effect early in January, the seasonal news vacuum is effortlessly filled with collective commuter anger. It spreads across the nation just as the Christmas and new year engineering closures abate. Kicking 3: how can the train companies charge so much for rubbish service?

Train performance in two areas of Britain – the Thameslink corridor through London and northwest England – has indeed been lamentable this summer, due to horribly botched new timetables. The operational shortcomings in rail services could fill several long reads. But first some truths about train fares need to be told.

Britain has the most commercially aggressive fares in Europe, with the highest fares designed to get maximum revenue from business travel, and some of the lowest fares designed to get more revenue by filling more seats

Mark Smith, international rail guru

You may be reading this while standing on a commuter train to or from Britain’s busiest terminus, London Waterloo, for which you have paid what feels like a small fortune. If so, please forgive me as I state an uncomfortable fact. It is a widely held view that our trains are simultaneously too expensive and too crowded. But those two complaints are mutually exclusive.

The supply of seats on rush hour trains on Southwestern Railway is at a maximum, at least until double-deck trains or digital signals are introduced. Demand for those seats outstrips supply, as everyone on those “full and standing” trains will testify. In other industries, prices for peak services would rise to deflect demand on to quieter departures, and everyone would get a seat. But prices are artificially capped.

There are plenty of reasons to keep commuter fares down. Affordable rail travel expands the pool of labour available for London, which anchors the UK economy. It reduces traffic congestion, and the environmental impact of commuting.

On a more personal level, suppressing the natural inclinations of the market facilitates more attractive lifestyles – such as a home in a pretty Surrey village with a decent local school, along with a good job in the City – even if the commuters don’t enjoy the actual journey.

Crucially, a very small but highly significant group of people believe that keeping a lid on fares will keep them in work. When ticket prices rise, MPs traditionally lead the howls of protest.

Since the railways were born, so far as I know no elected representative has ever ventured that if some peak fares were put up a bit, and others were cut, everyone could have a more comfortable journey.

On occasion, I have suggested that radical price reforms such as “super-peak” fares for London arrivals between 8am and 9am and commensurate fare cuts at the edges should at least be considered. The heckling – from MPs as well as normal people – is ferocious.

The Rail Delivery Group (RDG) is currently evaluating nearly 20,000 responses to a fares consultation this summer: “The first to give stakeholders, employees and the public across the length and breadth of the country the chance to have their say about what a future fares system should look like.”

The RDG and Transport Focus, the passenger watchdog, have stressed that the resulting proposals it will put to government will be “revenue neutral”.

You don’t need my help to translate that phrase as meaning some fares will fall, and others rise. History shows that those who are penalised by change shout 100 times louder than the beneficiaries.

Fear of the travelling public explains why, a generation after rail privatisation, many other absurdities remain.

3138%

Expected increase in cost of annual season ticket from Epsom to London

Since the first privatised trains ran in 1995, UK rail fares have become progressively more complicated, with a vast array of new ticket variations but no cull of the fare types that were “baked in” when British Rail was broken up.

Every train operator is hamstrung by the Ticketing and Settlement Agreement of 1995. This 415-page document stipulates that each of the 2,500 stations in Britain must have a fare to all of the others – an obligation akin to forcing easyJet and Ryanair to offer through-tickets to airports worldwide, while giving one-third off fares to a random bunch of passengers holding specific cards, and providing a cardboard ticket to anyone who demands one.

Over the same timespan, the budget airlines have transformed public attitudes to ticketing – starting with the reasonable principle that a return journey should be priced at the sum of its two parts.

On long-distance journeys on the railways, in contrast, off-peak returns cost exactly £1 more than off-peak singles. Is that because train operators want to reward us by offering twice as much travel for a tiny extra cost? No. It’s because the return fare is capped by government at a level that is below what the market would allow. In a bid to try to win back some of the lost revenue, the off-peak single is priced disproportionately high.

Airline passengers are now attuned to the reality that the fare for their chosen departure is determined by how much others are prepared to pay. Don’t blame British Airways, easyJet or Ryanair for driving up the price of a half-term trip to the Canaries: they are simply allocating the scarce asset of a seat from Gatwick to Tenerife to the highest bidder.

Yet every now and again, a story emerges of an individual who flew some absurd route via continental Europe to get from London to Edinburgh, and still saved money compared with the rail fare.

Since the railways were born, so far as I know no elected representative has ever ventured that if some peak fares were put up a bit, and others were cut, everyone could have a more comfortable journey

Invariably, such tales do not bear scrutiny: the flights are all booked in advance, and compared with “walk-up” tickets for the trains. A fair comparison would involve buying an on-the-spot flight from Gatwick to Berlin and another to the Scottish capital, running into many hundreds of pounds.

On the subject of Germany: back to my angry fellow traveller. “German train fares are so much more reasonable,” he insisted.

As a very frequent rail traveller, I envy the Germans for some of the innovations they enjoy. Anyone can spend €62 on a card that buys 25 per cent off fares; there is no requirement to be young/old/a parent/in a relationship. And €4,270 buys an “access all areas” pass allowing unlimited travel for a year. That is barely £10 per day for some of the finest trains in Europe.

The long-suffering taxpayer who never goes near a train yet who helps pour tens of billions of pounds into the UK rail industry might baulk at such deals in Britain.

Yet as the international rail guru Mark Smith demonstrates, the average rail passenger in Germany and many other European countries envies us.

Mr Smith, who runs the Seat61.com website, looked at fares on four journeys of near-identical length: London to Sheffield, Kassel to Nuremberg, Rome to Florence and Paris to Dijon.

He first priced them up for booking an off-peak train a month ahead, which the UK won hands-down; half the price of the Italian and French equivalents, and 40 per cent of the lowest German fare.

Looking just 24 hours ahead, the British advantage over Germany is even stronger, while the UK is still well ahead of the cheapest Italian and French fares.

€4,270

Cost of unlimited travel for a year in Germany

For walk-up peak-time fares, it all turns round. London-Sheffield is vastly more expensive than continental tickets: 70 per cent higher than Germany, 153 per cent more expensive than France and almost three times pricier than Italy.

Mr Smith’s conclusion: “Britain has the most commercially aggressive fares in Europe, with the highest fares designed to get maximum revenue from business travel, and some of the lowest fares designed to get more revenue by filling more seats.”

Anyone constrained to buy on the day and travel at peak times may still be feeling miffed. But if you don’t like the fare, choose a cheaper one.

Many travellers – and taxpayers – say they are in favour of renationalisation of the railways. With train operators typically taking a 3 per cent margin, that is certainly an important part of the debate. But the notion that government-run trains are automatically less expensive than privatised services is overturned on the east coast main line; for the cheapest “walk-up” deals between London and Yorkshire, the open access operators Hull Trains and Grand Central are significantly cheaper.

Most lines do not have such options. Happily, there is almost always a way to save. The post-privatisation policy was intended to protect the travelling public against excessive fares rises or disadvantageous changes to conditions. But the result is a system riddled with inconsistencies, which are ripe for exploitation.

As successive governments fail to grasp the nettle of fares reform, it is easy to identify absurdities in the fares “system” which cut costs.

I believe the most expensive inter-city train journey in Britain is between Rugby and Watford Junction, at 96p per mile. But choose a Virgin Trains service that pauses at Milton Keynes and buy two separate tickets, and the price almost halves.

Split-ticketing, as the technique is known, is so well-established that on the GWR line from London Paddington to Bath and Bristol it even has a name: the “Didcot Dodge”, after the station where shrewd peak-time passengers break their journey, at least on paper.

Technology has come to the aid of the novice ticket-splitter, with a range of apps that explain how to cut the cost of many journeys.

“Can’t you quieten down about split tickets?” an executive at one of the big train operators whispered after I wrote about the benefits of breaking a London-Newcastle journey at Doncaster. Certainly not. Suppose more rail passengers latch on to these perfectly legitimate hacks, as well as absurdities such as an Edinburgh-Lancaster off-peak ticket costing £5 more than one to Preston, miles further. If rail revenue falls significantly, it may at last precipitate the “root and branch” reform of fares that everyone says is necessary, but no one seems willing to achieve. And my fellow passenger from Manchester may feel less hard done by.