My race may have played a factor in my college rejections, but I support affirmative action

Former Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust once stated that Harvard could fill its entire class twice over with valedictorians.

And while I certainly wasn’t in the running to be a valedictorian at any point in my K-12 education, I like to think I had a reasonable shot at an Ivy League school when I was a high school senior.

I had a perfect SAT math score, 34 on the ACT and 1,000-plus volunteer hours; was debate team president, class president, editor-in-chief of a school publication and principal cellist of a local orchestra; and took some double-digit number of AP classes at my elite, private college preparatory school.

In short, I was just like many others vying for the Ivy League – and probably very similar to the anonymous Asian American students who are having their failures exploited by Edward Blum through his lawsuits against Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

I got rejected from those two colleges – and actually from every college I applied to except for one: the University of Florida, a school that does not factor race into its admission decisions.

So-called 140 SAT point 'penalty'

Internalized pressure to make my parents and high school proud fueled my grief and anger. I searched for a cause to blame, and it was also impossible for me not to wonder to what extent race played a factor in my numerous rejections.

When looking for a scapegoat, the outdated, oft-cited, often misrepresented data from two Princeton sociologists who found that Asians in the college admissions process had a so-called 140 SAT point “penalty” felt a lot more solid than the possibility that my grades and essays weren’t received favorably.

The fact that the only school I was accepted to couldn’t factor race into its admissions … that sold it to me: My race might have played a factor in my rejections.

I printed out the dozen or so college rejections letters and taped them to the wall of my bedroom, to remind me of my failure (and because I am a person partially powered by spite).

The University of Florida, which some students in my class jokingly (and endearingly) called “the Harvard of the South,” treated me well. I got an excellent education that could easily rival those in the Ivy League, and I made special effort to successfully best Ivy League teams whenever I’d compete against them in extracurricular activities.

One noncompetitive extracurricular activity I did partake in was reading admissions essays for UF’s honors program.

It was in that position that I really started to understand the other side of the college admissions process. After reading thousands of essays about involvement, I also started to understand how unextraordinary of a high school senior I actually was. (Disclaimer: Student readers are blind to the race and test scores of applicants.)

Serving as an admissions reader and my overall time in college helped cement my beliefs about affirmative actions: I support it.

“Crusaders” against affirmative action dream of a race-blind world where all people do is tweet that one quote from Martin Luther King Jr. about judging people about the content of their character.

The reality is that without affirmative action, colleges will still play favorites and that will have an impact on the diversity of their classes.

For those unfamiliar, legacy admissions is the practice of giving people preference in the college admissions process because they share a familial relationship with an alumnus. It sounds a little more racist if you think of it as some people getting into a college because they share DNA with someone who graduated from there.

It is hard not to think of John F. Kennedy’s Harvard admissions essay when discussing legacy admissions. A mere five sentences long, the essay’s strongest line is “I would like to go to the same college as my father.”

Close to a hundred years later, we see that 43% of white students at Harvard are legacy, athletes or related to donors or staff. The numbers do not hold the same for minorities, including Asian Americans.

Using Asians as a racial mascot

At the end of the day, affirmative action helps Asian Americans – especially underrepresented subgroups – and a supermajority of us support it.

And to those who don’t support it, I get it.

It hurts because the American dream tell us that if you work hard enough, you can do anything. But that’s just not the way it is in reality. Expecting to get into a particular college just because you worked hard is called entitlement. Almost everyone who applies to selective colleges has worked hard in some way. Everyone has merit to some degree.

It hurts because when we read the lawsuit’s (contested) claim that Asian American applicants to Harvard scored lower on personality traits, it reminds us the implicit bias we face every day in our classrooms and workplace. Yes, admissions offices can be more diverse and admissions officers can be better trained to overcome their biases. However, I can’t see this one claim as good enough reason to end affirmative action across our country.

What really hurts is seeing Asian Americans being used by white people like Edward Blum to attack a system that benefits ourselves and other minorities. The playbook is so old, there are numerous ways to describe what is going on: Asian Americans are being used as a racial mascot, used as a racial wedge and are being racially triangulated against other minorities by white people in their fight against affirmative action. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

I learned and grew from my failures. I live a somewhat happy life (given what’s going on in the world these days) and contribute to society, making it a better place.

Maybe my race played a role in my rejection. Maybe it didn’t. Life goes on if you don’t get into the college of your dreams.

Affirmative action, as a principle, serves to help all underrepresented groups of people, including those from rural areas or lower socioeconomic status. Race really is just one of the many, many factors college admissions officers look at through their holistic review processes.

To scapegoat race for an admissions rejection would be, well, unfair.

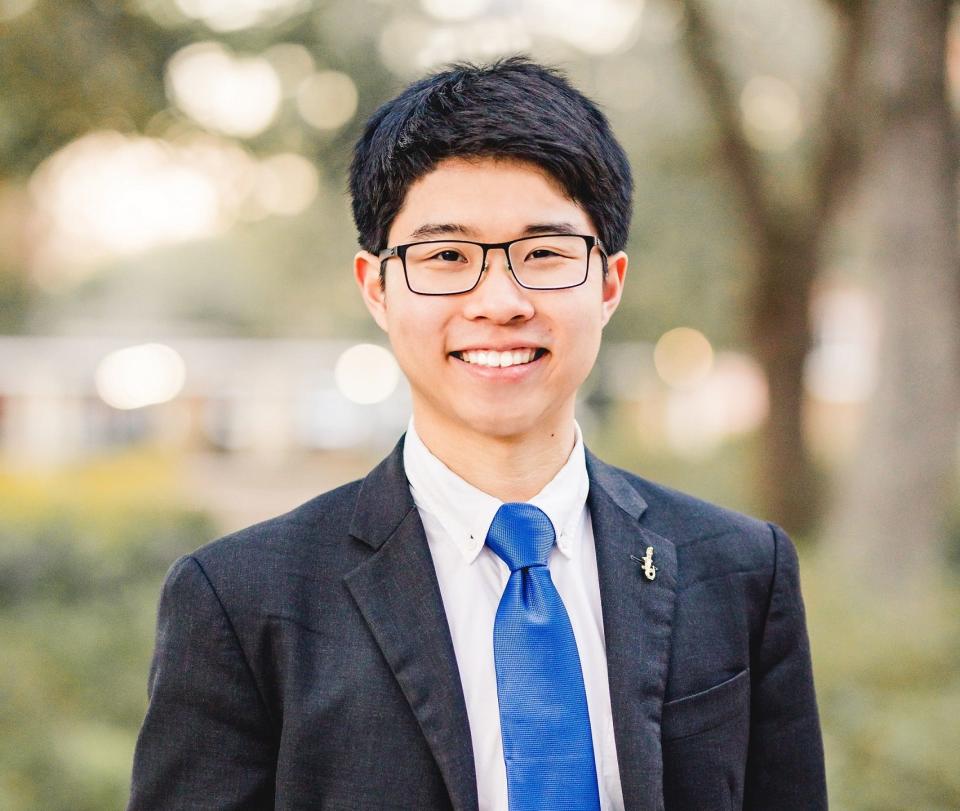

Zachariah Chou is an opinions coordinator for the USA TODAY Network.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Affirmative action kept me, an Asian student, out of my dream college