The Push For Christine Blasey Ford to Testify Plays Into A Damaging Myth About A Survivor's 'Duty'

Politicians criticizing Christine Blasey Ford for not wanting to testify Monday in a Supreme Court confirmation hearing on Brett Kavanaugh are inadvertently holding her solely responsible for policing her alleged attacker, say experts on sexual assault.

Research on the motivations of sexual assault survivors reveals that those who cooperate with law enforcement investigations are often spurred on by the hope that they can help prevent another person from being victimized ― if not by stopping their own attacker, then by sharing a story that could help others avoid or survive the trauma of an assault.

The California psychology professor, who goes by Christine Blasey professionally, has hinted at this motivation, but those who study the behavior of sexual assault survivors find that it can be used by others to coerce cooperation a victim isn’t comfortable with or ready for. It can compound the guilt that survivors might already feel for not being able to prevent or stop their own attack.

In the few public statements she has made, Blasey has been frank about the tremendous internal struggle she had in coming forward with her allegation that, when they were teens at a party, Kavanaugh pushed her into a bedroom, turned up music to drown her out and tried to take her clothes off while holding his hand over her mouth.

In her July 30 letter to Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), which was read aloud to CNN, Blasey wrote, “It is upsetting to discuss sexual assault and its repercussions, yet I felt guilty and compelled as a citizen about the idea of not saying anything.”

“I feel like my civic responsibility is outweighing my anguish and terror about retaliation,” Blasey later told The Washington Post’s Emma Brown for an article about why she came forward.

Blasey is trying to stop Kavanaugh from being confirmed to a lifetime Supreme Court seat, not trying to prevent other women from being personally victimized by him. Still, her statements reveal the struggle that countless sexual assault survivors grapple with: a sense of responsibility for stopping an assailant, and guilt if they fail to do so.

Rebecca Campbell, a professor of psychology at Michigan State University who has studied sexual assault survivors for 25 years, said that preventing someone else from being victimized is one of the most commonly cited reasons survivors cooperate with the criminal justice system.

“It’s a very, very gut-wrenching equation for them,” Campbell said. “Wanting to protect others, wanting to protect public safety, making sure that it doesn’t happen to anyone else and feeling that responsibility.”

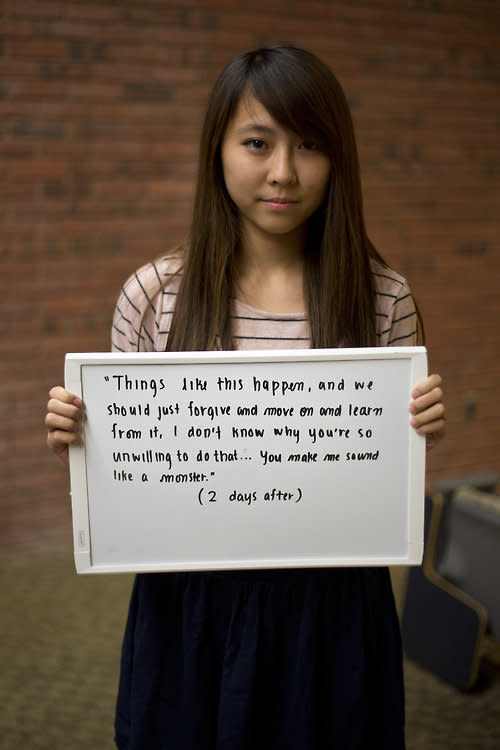

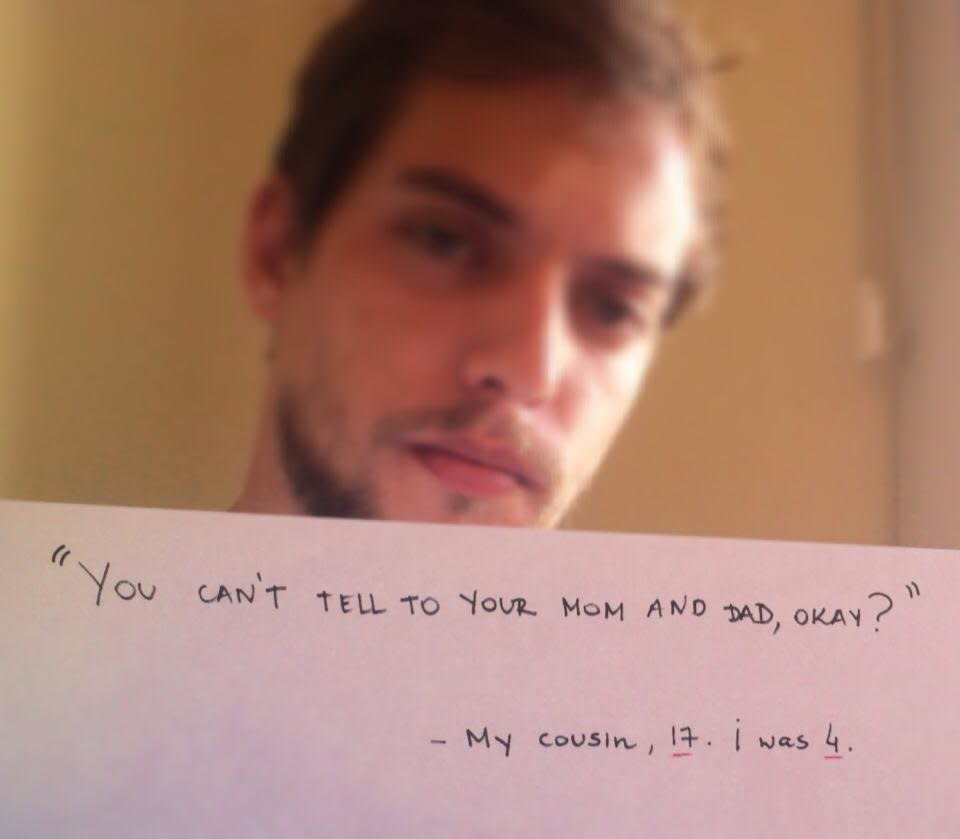

But if that pressure comes from the outside ― say, law enforcement pressuring a survivor to report or testify against her attacker ― this altruistic motivation to spare others from pain and terror can be transformed into something more insidious that can make survivors feel blamed.

Silence is complicity, as the saying goes, and, in the public narrative, the victim is transformed into victimizer if he or she doesn’t say something.

“It can feel very pressuring, and many survivors have used the word ‘manipulative,’” Campbell said. “They’re being manipulated to do something that they don’t feel ready for.”

Sarah Layden, a public policy expert at the sexual violence survivors organization Resilience in Chicago, noted that some survivors feel this motivation naturally, but it doesn’t mean that it should be used to pressure them to report.

“Survivors should be encouraged to come forward through empowerment, support and being believed, not via the pressure to prevent others from being harmed,” Layden wrote in an email. “I just caution communities putting this type of pressure on survivors due to the internal pressure they already feel around this, compounded by feelings of self-blame, guilt, fear of not being believed or of retaliation, the stigma of sexual assault and so much more!”

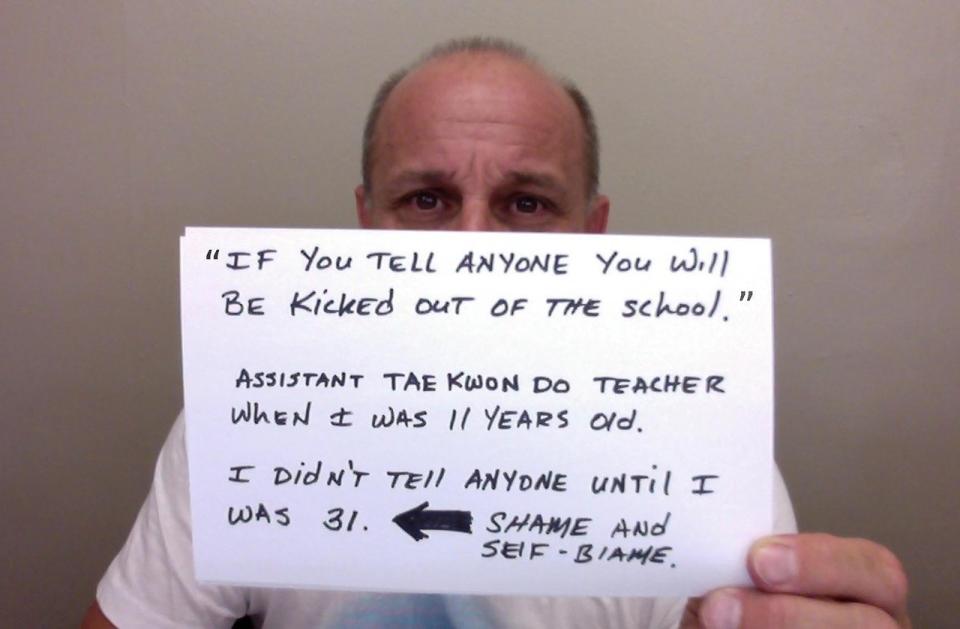

Casey Gwinn, CEO of Alliance for HOPE International in San Diego, knows this on a personal level. When he was 11, a stranger molested him in a supermarket while his mother was somewhere else in the store. After it happened, he thought often about what he could have done at the time.

“I should have yelled. I should have screamed. I should have done something,” Gwinn said. “But I didn’t. I froze. I didn’t know what to do.”

He never told anyone about it until eight months ago ― 46 years later. He began talking about it first among his family, then at events to promote his new book. And the questions he encountered insinuated that Gwinn, at 11 years old, didn’t do enough to stop a man who probably went on to hurt other people.

“Just the very voicing of it felt like it was my fault,” Gwinn said. “That if there were other victims, it was my fault, when, in fact, it’s his fault.”

“He’s the one who did it,” he continued. “And it’s his responsibility to be held accountable for his conduct.”

This idea that assault victims are responsible for the future predation of their abusers is an old one, and it has disturbing legal ramifications, according to advocates for assault survivors. Prosecutors who want to put rapists and predators behind bars have the ability to detain and jail assault survivors if they believe the victims do not want to willingly testify against their abuser. In the most infamous cases, the survivors suffer further abuse in jail from other inmates or guards. Critics of this practice say that there is other evidence beyond the testimony of the victim that can land a conviction for prosecutors.

Gwinn, whose organization works with municipalities to create centers where victims of sexual assault can find the services they need in one place, says that Alliance for HOPE never takes the position that the victim is responsible for coming forward in order to prevent more violence.

“What we try to say is, we as a society are responsible for holding the perpetrator accountable,” he said. “The focus isn’t on trying to hold the victim accountable.”

Blasey has already taken the most difficult step, which is to come forward about her experience, Gwinn said. Instead of attacking her and her statement, it’s time to turn the spotlight on Kavanaugh, he said.

Also on HuffPost

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.