Pure Heart

IN A WAY, THEY WERE LIKE SO MANY OTHER COUPLES VISITING NEW YORK CITY AS NEWLYWEDS. With no kids to keep an eye on, they could stroll the city streets hand in hand, go for a run in Central Park, drop into glitzy stores and shop without worrying about the family budget. But Ryan and Alicia Shay traveled to New York last fall with more than sight-seeing and idle fun in mind. Ryan had a race to run.

It was the U.S. Men’s Olympic Marathon Trials, the quadrennial event that would produce America’s team for this summer’s Olympics in Beijing. And at 4:30 a.m. on Saturday, November 3, 2007, the morning of the Trials, Ryan and Alicia slid out of their Manhattan hotel bed for a race that wouldn’t begin until 7:35. Ryan had to grab a quick breakfast, though, and then catch the 5:20 bus to the start at Rockefeller Center. This was no time to be late.

Ryan had prepared most of his 28 years for this day. He was not yet 10 when he began racing blustery cross-country meets in northern Michigan. In high school, college, and beyond, few could match him. The longer the distances, the greater his success. The marathon seemed his perfect event, demanding, as it did, precise attention to detail and endless 140-mile training weeks. Tougher than the rest? That was Shay. More dedicated. More single-minded. More solitary.

For many runners, the sport provides a social outlet. At Shay’s level, though, there is little company, not when you’re aiming for a 2:11 marathon and a spot on an Olympic team. For the most part you have to go it alone. But that was okay. Ryan embraced everything about his sport, his event, and the quest for a life-changing Trials performance. He knew what it demanded: one day, one race, one man against the distance.

Alicia Shay didn’t go to Rockefeller Center with her husband of not-quite-four months. Ryan said it wasn’t important; he’d rather see her in Central Park, where the marathoners would run five loops. They said their goodbyes at the 5:20 bus.

A few days later Alicia recalled the moment. “I thought of all the things I could tell him for encouragement,” she says, “but in the end, I decided to just say, ‘I love you.’”

“I know,” he replied with a kiss. “And I love you, too.”

WITH ITS POPULATION OF 990, Central Lake, Michigan, located about 225 miles northwest of Detroit, is the kind of hamlet where the “Welcome To” sign says: “Home of the 1980 Class D Girls Softball State Champions.” Downtown measures two blocks by two blocks and is anchored by Rocket Rob’s Village Pizza and Crossings Bait Shop. “I tell people it’s the Mayberry of the North,” says Quinn Barry, a Central Lake high school teacher and coach. “It’s a town full of hard-working people who feel a strong connection to each other.”

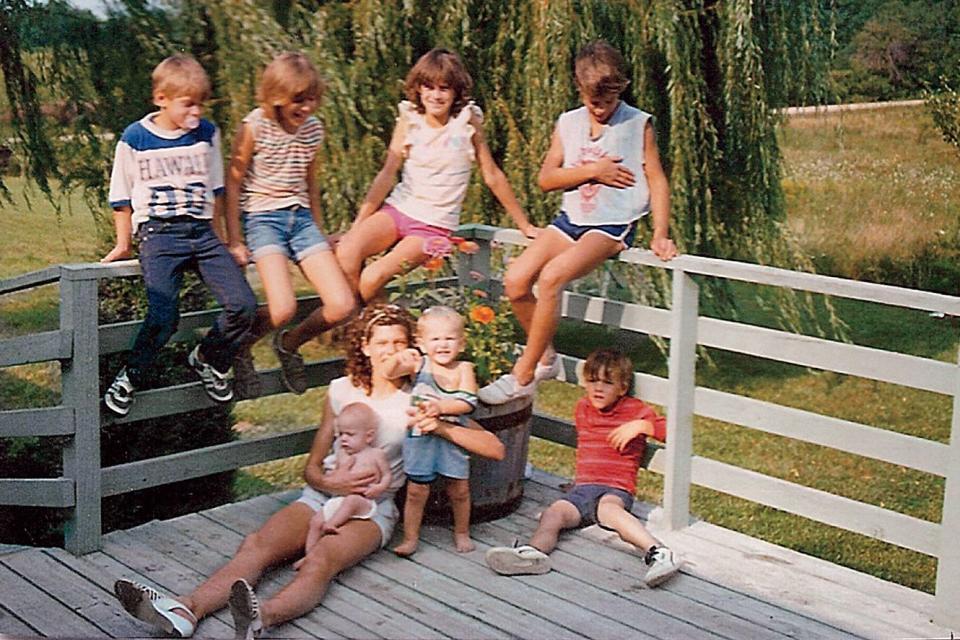

The Shay family moved to Central Lake from Nashville, Michigan, when Ryan was nine. Ryan was a scrappy kid from birth. He didn’t have any choice. Not when he was the fifth child in a family that would grow to eight. Not when his only older brother, Case, five years his senior, was fast, tough, and unbridled. “I was just a punk kid back then, and no great brother,” says Case, now a teacher in South Korea. “Ryan and I had a sibling rivalry. He wanted to do everything I did, and I beat the crap out of him plenty. He couldn’t keep up with me at first, but he liked challenges and had a high tolerance for pain.”

While Ryan couldn’t match Case for many years, he never stopped trying. He mimicked everything Case did-high-jumping, guitar-playing, schoolwork-always aiming to surpass his older brother. “He finally started beating me in running when he was about 20, a sophomore in college,” Case admits.

Ryan seemed to have only one gear, full-speed, which he applied to everything. Barry was one of the first to witness Ryan’s raw competitiveness, recalling it with a mix of smiles and horror. In eighth grade, Ryan played on the Central Lake basketball team. In one game, he scored nearly half the Trojans’ points, but the team still lost. In the postgame handshake lineup, Ryan blasted each opponent with a curse word. Barry, the school’s athletic director, yanked him aside and explained the error of his behavior. “But I really wanted to win tonight,” the young athlete protested. Then he made his apologies.

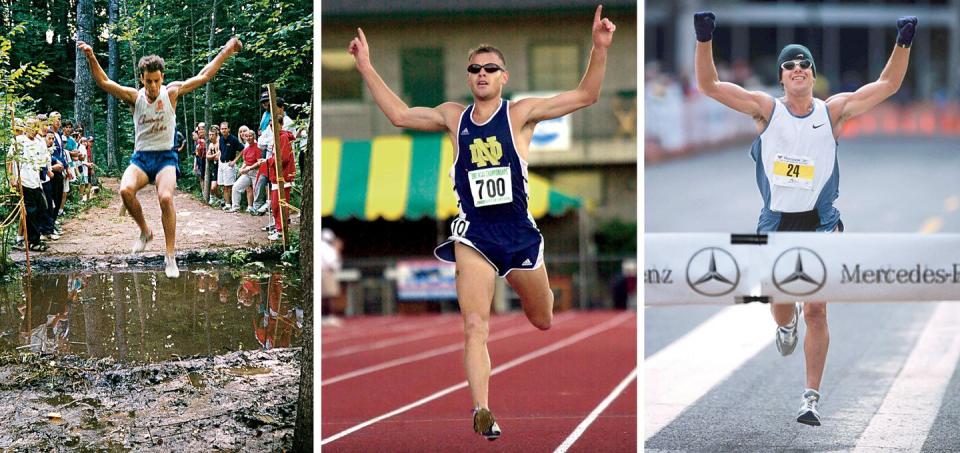

It was as a runner, though, that Ryan left his mark at Central Lake High, whose cross-country and track teams have been coached by his parents, Joe and Susan Shay, for two decades. Joe, 58, is a former quarter-miler grown portly. He moves and speaks slowly, suffers from diabetes, and doesn’t look the part of a driven track coach. He has more the philosopher’s approach to the sport, with a library exceeding 100 track and running books. He has examined each carefully, looking for new wisdom to inform his coaching. Susan, 56, is the Central Lake school librarian, more angular, quiet, and private than her husband. All eight of their children ran for Central Lake, most with distinction. But Ryan far outshone the rest. He won 11 state titles, including four straight Michigan state championships in cross-country, a mark that’s never been matched. His final one was perhaps the most memorable. He not only won the small-school title, but his winning time was faster than every Michigan high schooler’s, including the kids from the well-heeled suburban towns down south.

The titles aside, Ryan’s self-confidence proved he had big-time ambitions beyond his small-town roots. Once, when a classmate expressed admiration for a medal Ryan brought home from a regional meet, he told her, “Someday this is going to be a gold medal from the Olympics.”

Yet, for all his victories, Ryan felt few understood his passion for excellence or his attraction to distance running. The locals couldn’t fathom why a teenager would bull his way through 10-mile training runs in blizzards and sub-zero temperatures. Ryan was 15 when his father gave him a copy of Pre, the biography of American distance legend Steve Prefontaine. Before he died in a car crash at 24, Pre was known for seizing control of races like no American before him. He’d run boldly from the front and might have won an Olympic medal if he had been willing to settle for silver or bronze. He wasn’t. He went for the gold, and came close, fading to fourth in the final meters of the 1972 Olympic 5,000. It took Ryan just a few days to read Pre cover to cover.

“What did you think?” Joe asked his son later.

“At last, someone who understands me.”

Soon the walls of Ryan’s bedroom were covered with Pre stories and posters, and he began training even harder. He stuck to an unwavering schedule: Run in the morning, go to school, run at practice, and come home and complete all his homework before eating. He’d never allow himself to touch dinner until his studies were completed. It wasn’t a family rule; it was his own self-imposed discipline. In 1997, he graduated from Central Lake with a 4.0 GPA. He was also class president and covaledictorian. “He had such a sense of purpose and so much discipline,” says Joe, a touch of wonder in his voice. “He simply wouldn’t allow himself to be distracted by outside influences.”

MIDTOWN MANHATTAN WAS STILL DARK WHEN THE BUSES ARRIVED AT ROCKEFELLER CENTER. The 131 men running the Trials filed out and trudged down to the concourse level, beside the famed skating rink. Meb Keflezighi. Alan Culpepper. Ryan Hall. Dathan Ritzenhein. Abdi Abdirahman. Brian Sell. They were all here and they represented the greatest assemblage of American distance talent ever gathered for one marathon. Some folded themselves into chairs, some sat against a wall, some sprawled full-length on the floor, looking bedraggled and groggy, conserving every kilojoule of their energy supply. In fact, they had never been more focused or adrenaline-charged. Four years had passed since the last Marathon Trials. It would be another four years until the next. Carpe diem. Seize the day. Carpe viam. Seize the road. It was time.

Stretching guru Phil Wharton assisted several runners through easy leg exercises. Ryan Shay was one of the last he worked on, just enough to get the blood flowing. They were friends, both living in Flagstaff, Arizona, and Ryan had received regular treatments as he increased his Olympic Trials training. Before sending Ryan off, Wharton said, “Run patient today.”

“That’s the plan,” Ryan offered back.

Ryan’s coach, Joe Vigil, was more emphatic. He had coached Deena Kastor to an Olympic medal in 2004. He is a master in the art of starting-line advice. While he expected Ryan to know what he needed to do by now, Vigil left nothing to chance. He had trained Ryan to run a 2:11 marathon, and thought he was ready to do just that. “Stay away from the front, but stay in the hunt,” he told his runner. “It’s a breezy morning, a good day for following.”

Vigil’s final words: “Run with confidence. Run with emotional control.”

FOR A KID FROM A SMALL, REMOTE TOWN, RYAN SHAY DREW PLENTY OF ATTENTION FROM BIG-TIME COLLEGES. He made recruiting visits to three-Tulane, Arizona, and Notre Dame. Ryan’s weight-as much as 170 pounds in high school-and muscular upper-body build drew attention from the runners he met. On his trip to Arizona in 1997, he met Abdi Abdirahman for the first time. Abdi initially assumed that Ryan was a football linebacker. Ultimately, he chose Notre Dame. “He liked that it was a top-25 academic school and a top-10 running school,” says Nate Shay, who later followed his older brother to South Bend. “Those two things were both really important to Ryan.”

Still, not everything came easily when he got to college. In high school Ryan often ran alone and won races by huge margins. Notre Dame was different. Before Ryan’s first race in a Fighting Irish singlet, his coach, Joe Piane, instructed his runners to stick together for three miles. After that, they were free to run as hard as they wanted. “He must have misunderstood me,” recalls Piane with a knowing twinkle in his eye. “He stayed with everyone else for about three strides before taking off. Afterward, I asked him about it. He said, ‘Coach, I came to Notre Dame to run fast.’”

He showed a similar bluntness in the classroom. Early in his freshman year he submitted a 10-page paper for an English class. In it he explored his running dreams and the ways to achieve them. He titled the paper, “American Distance Running: Getting Lapped in the Fast Lane.” The paper began, “My goal in life is to become an elite distance runner. I want to indulge in victory and be able to tell myself that I am the best at what I do.” It went on to excoriate high school runners for not training hard enough-”The youth of today are basically lazy, and distance running is a lot of hard work”-and postcollegiate runners for not believing they could beat the East Africans. He concluded the paper by invoking Steve Prefontaine, who ran “to see who has the most guts,” and by saying that he and others must follow Pre’s example. “This is what will make Americans great runners,” he wrote. “This is what will make them heroes for eternity.”

Ryan was 18 when he handed in the paper, and he lived by its precepts. At Notre Dame he gained All-American honors nine times across three seasons: cross-country, indoor track, and outdoor track. There was no time of the year when Ryan wasn’t training and racing hard. Among his Notre Dame teammates, the stories of his effort are legion. Ryan never ran a mile slower than six-minute pace. No one could stay with Ryan on his cooldowns-or wanted to. He once helped lift Notre Dame to a conference title with a bum leg that had tormented him for two months. “He was the most tenacious runner I ever had,” says Piane, Notre Dame’s coach for the past 33 years.

The favorite tale is one that still stirs disbelief. During one of his infamous blizzard runs-he never let weather of any kind interfere with a workout-Ryan had completed just three miles of his scheduled 16-miler when a car knocked him down at an intersection and ran over his shinbones. Bouncing up, he checked himself out and felt fine. He still had 13 miles to go, and damned if his training log wasn’t going to report that he had finished every one of those 16 miles.

When he later returned to his apartment, he told his teammate, Sean Zanderson, what had happened. Zanderson searched Ryan’s face for a telltale grin. None. He looked at Ryan’s shins. Bruised and bleeding. He told Ryan he’d better get himself over to the hospital for X-rays. “Yeah, I guess you’re right,” Ryan said. But first he insisted on doing his extensive postrun stretching routine.

Appropriately, Ryan’s best college track race came at the University of Oregon’s Hayward Field, the track made famous by Prefontaine’s many beat-me-if-you-dare efforts. Ryan was the fourth seed in the 10,000 meters of the 2001 NCAA Track & Field Championships. The first lap unfolded at a pace so pedestrian that he found it sacrilegious. Would Pre ever run this cautiously? No way. So he surged to the front and stayed there for the next 24 laps, winning by a wide margin. “If I was ever going to win a big race,” Ryan said afterward, “that was the place I wanted to do it.”

A LITTLE BEFORE 7 A.M. THE RUNNERS BEGAN SHUFFLING UP THE ROCKEFELLER CENTER STAIRS TO THE STREET LEVEL TO BEGIN THEIR WARMUPS. Like all marathoners, they checked the weather first. It wasn’t nearly as bad as most had feared 24 hours earlier, when forecasters were predicting that remnants of Hurricane Noel would strike Manhattan with heavy rains and wind gusts to 40 or 50 miles per hour. Vigil was right: It was breezy. But just breezy. No rain.

Ryan warmed up in part with Abdirahman, a race favorite and an occasional training partner in Flagstaff. They did strides on 50th Street, between Fifth and Sixth avenues, then wished each other well before removing their sweats and taking their places at the start. “He was in good spirits. There was nothing wrong with him,” says Abdirahman. “He told me: ‘Abdi, you’re the class of the field. Just believe in yourself, and run your race.’ I actually thought he had a good chance to make the team. He had a great strategy: He was going to stick with Brian Sell.”

Moments before the start, Ryan Hall, another favorite, appeared out of nowhere. Hall had been delayed in his final preparations. Now he was looking for a spot on the front line. He saw Shay, whom he knew, and figured his friend would open up a space for him. Shay did. “Good luck,” Shay told him. “Go get ‘em.” Hall was wearing mostly blue, with a number two attached to the side of his shorts. He was the second seed in the field, based on his qualifying time. Shay wore a white singlet and black shorts, with the number 13 pinned on them.

Behind the small but elite field, the Gothic-style towers of St. Patrick’s Cathedral reached upward.

RYAN SHAY HAD HEADED OFF TO COLLEGE WITH ONE PRIMARY GOAL-TO BECOME THE BEST RUNNER POSSIBLE. And he would let few things distract his focus. As in high school, he had little time for girlfriends while at Notre Dame. He dated and had relationships, but none that endured. Dating wasn’t his big concern. Training harder, getting faster, making it to the Olympics-now those were worthy aspirations. “Ryan was always so disciplined about everything he did, especially his running,” says his sister Sarah. “He was too serious to be the playboy type.”

After graduating from Notre Dame in 2002, Ryan needed a new way to nurture his running. At the time, veteran U.S. coaches Bob Larsen and Joe Vigil had just launched a small group called Team Running USA. They wanted to help talented postcollegiate runners stay with the sport and climb the rungs of international success. Among the first to sign on were Deena Kastor and Meb Keflezighi, both of whom would go on to medal at the 2004 Olympics. Larsen and Vigil subjected prospective team members to a battery of physiological tests at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, California, but also conducted in-depth interviews. They considered character just as important as VO2 max. They wanted team members to have the drive, purpose, and vision of a Deena or a Meb.

Ryan met several times with Vigil to discuss joining the group. Vigil has a Ph.D. in exercise physiology and doesn’t jump to hasty conclusions. He interrogated Ryan to judge if he had the right stuff, wondering, in particular, about a proposal that Ryan made: He said he wanted to go straight from the 10,000 meters to the marathon. No top-tier American distance runner had done this in 20 years-not since Alberto Salazar in the early 1980s. “Okay, but first sleep on it,” Vigil told the ambitious 22-year-old. “When you have, get back to me, and we’ll talk some more.”

Ryan didn’t need more time to think about his marathon dream, but he let several weeks pass before he called Vigil back. He didn’t want to appear rash, a quality Vigil disdained. When the timing seemed right, Ryan picked up the phone and dialed the man who would coach him for the next five years, becoming a second father of sorts. “I want to focus on the marathon,” he said.

Vigil didn’t actually care about Ryan’s choice of events. He only cared about commitment. “I was a little surprised by Ryan’s decision,” Vigil admits. “But he was so determined. I’m a very hard-driving coach, but he always did the work. He had a tremendous appetite for hard work.”

Ryan moved from South Bend to Mammoth Lakes, California, the high-altitude community where Team Running USA members do much of their training. One day Vigil assigned a 15-miler and sent his new runner out on some unfamiliar trails. Ninety minutes later, Shay hadn’t returned. Vigil got into his four-wheel-drive pickup truck and began scouring every dirt road in the area. He drove for hours and never located Shay, who eventually staggered into town in the late afternoon. Vigil figured that Ryan had run 15 miles and walked 31.

The next day was a “hard day” of interval training, 10 x 1000 meters. Vigil suggested that Ryan skip the interval repeats, given the calamity of his previous day. “Ryan wouldn’t even consider it,” says Vigil. “He figured if it was an interval day, you did your intervals. You didn’t make excuses.”

The work paid off. Ryan ran his first marathon in October 2002, finishing 15th at Chicago in an impressive 2:14:30. Four months later, he made headlines when he won the 2003 USA Marathon Championships in Birmingham, Alabama, in 2:14:29. He was the youngest national marathon winner in 30 years. “Ryan was one of the first to get the ball rolling for American marathoners,” says fellow Michigan native Greg Meyer, who won the Boston Marathon in 1983, the last American to do so. “He showed the way for the young guys who have followed him, like Ryan Hall and Dathan Ritzenhein.”

More importantly, Birmingham would be hosting the Olympic Marathon Trials a year later. Shay’s course tour and victory gave him a leg up on the competition. Suddenly, he was being mentioned as a possible Olympian. The dream unraveled when he sustained a hamstring injury in the final weeks of his training for the Trials. Then he aggravated the hamstring midway through the race and limped to the finish in 22nd place (2:19:20).

Shay was just 24. At the time of the next Trials, he’d be 28, a marathoner’s peak age. He’d have four more years of Vigil’s inspiration and another 20,000 miles of high-altitude training. He’d tinker with other aspects of his program. Perhaps he would drop the upper-body weight work; it only seemed to bulk him up. He could improve his diet to get leaner and meaner. He’d return to the track to lower his 10,000-meter PR. He’d keep looking for the best place to train-in California, Colorado, Arizona, wherever. He was a ramblin’ guy, single and unattached. No commitments. Except for the one he had made to himself a decade earlier: to work harder than anyone else.

The four years would pass quickly. When the 2008 Marathon Trials rolled around, he’d be ready for the race of his life. He was sure of that.

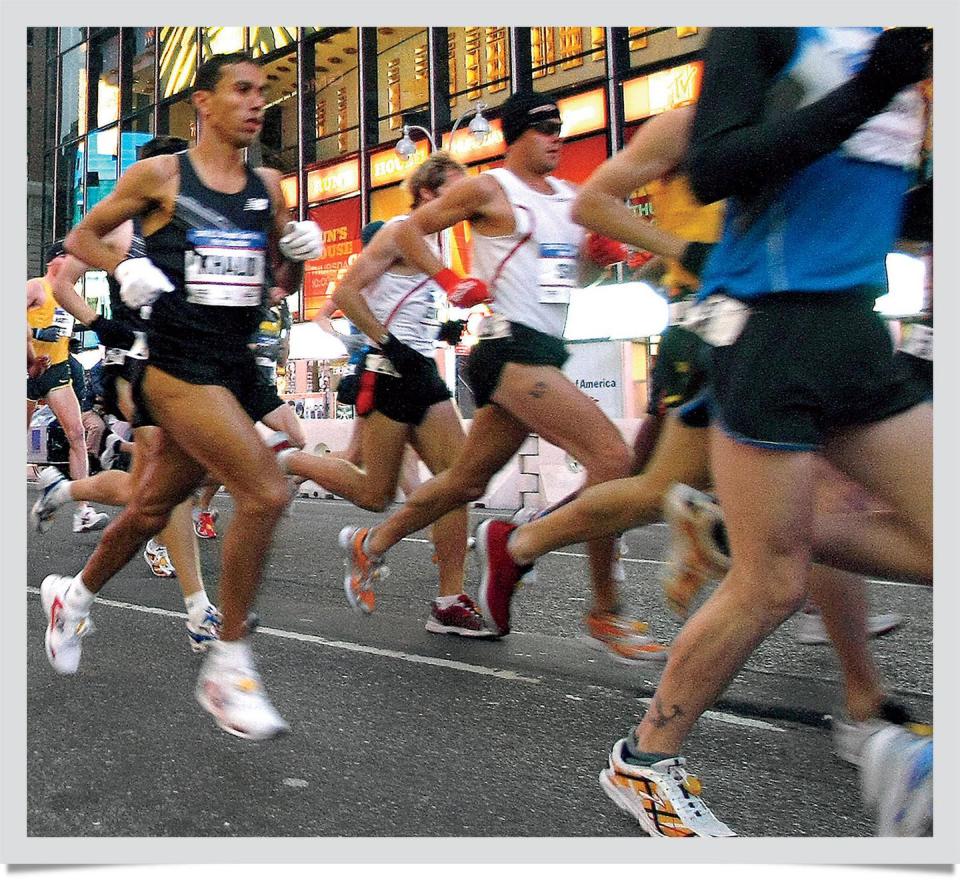

FROM ROCKEFELLER CENTER, THE MARATHON COURSE TURNED SOUTH FOR A QUICK SPIN AROUND TIMES SQUARE, as glittery as the rest of New York was dark on this gray morning. The race favorites ran cautiously, worried about the dim light, the 90-degree turns, and the pockmarked streets. They had but one goal: to stay on their feet until they reached the smoother roads of Central Park. That’s where the race would begin.

No one paid much attention when a couple of little-known runners spurted to the lead in midtown. The big guns ran in a large, slow-moving cluster. They covered the first two miles at 5:30 pace-practically a walk. That changed abruptly when the group reached the park at its extreme southern end and turned left for the first of five clockwise laps. Brian Sell dropped the pace to an honest five minutes per mile. Everyone had expected this of Sell, a bulldog runner like Ryan Shay, unwilling to accept a piddling marathon pace. Now it was official-the race was on.

Alicia Shay had positioned herself near the five-mile mark on the east side of the park, just south of the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir. It was a great vantage point. From here, the east roadway and west roadway are separated by just 500 yards. This meant that Alicia could sprint across the gap in less than two minutes. She is herself a champion distance runner who had recently won the USA 20K title, and she was wearing her racing flats. She figured she’d see Ryan at five miles, seven miles, and every two to three miles after that.

At 8:00 a.m. Alicia stood on the inside of the park roadway and craned her neck leftward, to the north. The runners would be appearing any moment now. Hundreds of other marathon fans had stationed themselves in the same vicinity. She didn’t recognize the first two runners to flash past-Michael Wardian and Michael Cox-but suspected they would soon drop back. She lifted herself up on tippy toes, and held her breath, waiting for the big group of prime contenders. That’s where she hoped to see her husband. In the lead pack, near its rear. Running as relaxed and economically as he could. His strength was his strength, and the longer he could conserve it, the better his chances.

Here they came. Sell and Abdi and Hall and Meb and a couple of dozen more. Yes, and her Ryan. He was running exactly where he was supposed to be, at exactly the right speed, five minutes per mile. That was the pace he had trained for, the pace he and Vigil had agreed upon. “Ryan looked great at five miles, smooth and controlled,” Alicia remembers. “He was at the back of the pack, right where he wanted to be.” She dashed across the park to the seven-mile mark, with high hopes and expectations.

RYAN SHAY BOUNCED BACK NICELY FROM HIS DISAPPOINTMENT AT THE 2004 TRIALS. In March 2005, he won the Gate River Run 15K in Jacksonville, Florida. It earned him his fifth USA national road championship in 26 months. Eight months later, he had a rare bad race in the ING New York City Marathon, when he strained several ligaments in his foot and finished 18th. But he knew what had happened; he could fix it.

The evening following that race he joined friends at Rosie O’Grady’s, an Irish bar in midtown Manhattan. Among those gathered was a recent Stanford grad and, like him, an NCAA 10,000-meter champion-someone, though, whom he had never before met. Her name was Alicia Craig.

A willowy, freckle-faced beauty and self-described “Wyoming girl,” Craig had grown up among cowboys and rodeo riders in Gillette, Wyoming, and at her family’s 14,000-acre Wyoming cattle ranch. Result: She’s not one to be easily impressed by macho posturing. She had heard about Ryan’s tough-guy veneer. That night, in a long conversation, she detected no trace of it. “He was so gentle and transparent and easy to talk to,” she says. “We had so much in common, it was almost crazy. I found that he was one of those people who, after you spend time with them, you feel better about yourself.”

Still, she left the restaurant and returned to her California training base with no thoughts that a relationship might blossom. She figured that she and Ryan would simply see each other on the national distance-running circuit. He had a bolder vision. A few months later, he moved to the Woodside, California, house where Craig was living with a handful of Team Running USA members. Ryan had heard that these guys were logging some long, gnarly workouts, and wanted in on the action.

Ryan Hall, a recent Stanford grad, lived nearby with his wife, Sara, and was one of the team members. Hall had never met Shay before but vividly recalls their first runs together. “We did a fast, hard 10-mile tempo run on a Saturday,” he says. “The next day was a long run, and Ian Dobson and I were taking it easier. But Ryan was out there hammering again. Ian and I looked at each other like, ‘Is that guy crazy or what?’ I soon learned that he was simply the hardest-working runner I’ve ever met.”

The team house didn’t afford much privacy, not with a half-dozen other runners in residence, but there were fleeting moments. One night, after everyone else had gone to bed, Ryan got out his guitar and began singing for Alicia. “He was obviously trying to impress me, because he was nervous and jittery and sweating so much,” she says. “I wanted to tell him it was okay to stop, for his own sake. But he stuck it out in typical Ryan fashion. He played and sang for two hours, and many of the songs-George Strait and other country-western tunes-were among my favorites, even though he couldn’t have known that. It was just the sweetest thing.”

The two hadn’t even had a date yet, but their friends could see the growing attraction. Alicia’s teammates began teasing her, warning her to be wary of that Shay fellow. His brothers, receiving e-mail photos of Ryan and Alicia, noted that the smirk was gone from his face, replaced by a look they had never seen before. “You could only call it a glow,” says Nate. “It was obvious that he had met the right woman, and he knew it. His life until then had been one long suffer-fest, what with all the moving around and the hard training every day. I think he was so relieved to finally meet someone he could open up to.”

Soon there was an official first date, but only after Ryan polished his burgundy Ford F-150 pickup truck for hours. And a second date. And the night when Ryan held Alicia’s hands, looked in her hazel eyes, and told her why she was the most amazing person he had ever met. “A lot of people thought Ryan was quiet and guarded,” she says. “But he was the exact opposite with me. He was so open and soft. He prided himself on always giving 100 percent, and that’s the way he loved me, 100 percent. I’ve never felt anything like it.”

Alicia’s family noticed the difference. Her sister Lisa Renee Tumminello, 38, was worried about Alicia’s health at the time. In her last year at Stanford, Alicia had fallen hard in a freak dorm accident, and suffered two years of head and neck pain and frequent waves of nausea. Her running had plummeted to an all-time low. Suddenly, that didn’t seem to matter so much. “As she grew closer to Ryan, Alicia developed a giggle I had never heard before,” says Tumminello. “She was filled with a childlike joy. She and Ryan were so playful with each other.”

At Thanksgiving 2006, Alicia took Ryan home to Wyoming for “the Ranch Test”-the scrutiny of her parents, siblings, uncles, and aunts, almost 20 in number. She didn’t realize that Ryan planned to ask their permission to marry her. At an opportune time, Alicia was dispatched on an errand with her young nieces and nephews. Ryan faced the adults of the Craig family in the kitchen, his hands folded stiffly in front. “He didn’t have anything planned or scripted,” says Tumminello. “But you could see that his face was so full of love, and he didn’t hold back anything. He said he wanted to care and provide for Alicia for the rest of his life. About halfway through, he realized he still had his baseball cap on his head, so he pulled it off and apologized. That was funny because no one in my family would care about that kind of thing. He was just so adorable.”

That night Ryan scoured the Internet and ordered a diamond engagement ring. He planned to propose at Christmas. But having passed the Ranch Test, he couldn’t contain his excitement. Two nights later, in a Colorado cabin, he dropped to one knee, popped the question, and slipped his honking Notre Dame ring onto Alicia’s slender ring finger. “It was the cutest thing,” she says. “Of course I said yes.” Then Ryan reached for his guitar, and this time, as he sang their favorite songs, there was no tension in the room, just tenderness.

They were married on July 7 in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, with Mount Moran towering over them in the brilliant, sunset sky. When Alicia picked the date, she had been merely trying to arrange her wedding around a cousin’s wedding the previous week. She didn’t realize that 7-7-07 had become a popular date for many young couples. Ryan detected another pattern in the numerals. The Beijing Olympic Games would begin on 8-8-08. He thought this a good omen.

Over the next three months, as he intensified his training for the Olympic Marathon Trials, she detected nothing unusual. Sure, he had some aches and pains as you would expect from running 140 miles a week, but nothing more. His last blood test before the Trials was his best ever. Competitive to the end, he couldn’t resist lining up his results against Alicia’s, and pointing out all the areas where he “beat” her.

On November 2, the day before the Trials, Ryan and Alicia joined Ryan and Sara Hall for an easy jog in Central Park. Sara and Alicia had been Stanford teammates, and Sara was one of Alicia’s bridesmaids. The men chitchatted about nothing of great import and stopped after four miles. “Sadly, I don’t remember much about that run,” Hall says. “He seemed the same old Ryan.”

The women logged an additional four miles, entertaining each other with stories of their husband’s prerace idiosyncrasies. Sara said her Ryan refused to eat in a restaurant before big races; she had to travel with a hotplate to cook spaghetti in their hotel room. Alicia said her Ryan could turn downright goofy before his races, the last thing you’d expect from such a straight-laced, routine-craving guy.

That evening proved a case in point. After a dinner out with Alicia’s parents and a brief stop so Ryan could buy Alicia her favorite chocolates, the couple retired to their hotel room. Ryan couldn’t resist a playful game with Alicia. He grabbed her hand and wouldn’t let go. She had to visit the bathroom? Too bad, he wouldn’t release her-not at first anyway. When she returned, he locked onto her again. “One of his missions in life was to make me laugh,” she says. “We had such a wonderful, light-hearted evening. I thought it meant he’d run well the next day.”

ALICIA DIDN’T SPOT RYAN AT THE SEVEN-MILE POINT, BUT WAS UNTROUBLED. The pack remained large and tightly bunched. No question, Ryan had burrowed himself into the midpack, content to let the others drag him along. When you did that, the running became effortless, and you preserved something for mile 20 and beyond. Ryan was in the perfect place. Alicia hurried back across the park, to about the nine-mile mark, to give him a big cheer there.

Her cell phone rang. It was Phil Wharton. He had ominous news. A friend had just phoned to say that Ryan had fallen. It appeared that he hit his head. Wharton was racing to the location just north of the Central Park Boathouse. “I’ll call you right back,” he said.

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

After several weeks, no one know why Ryan Shay died.

When Ryan Shay collapsed at 8:06 a.m. on November 3, at the 5.5-mile mark of the Olympic Marathon Trials, fast-acting spectators and volunteers quickly went to his aid. “Ryan was lying on the ground, and there were three or four people with him,” says Mark Weaver of Goshen, Indiana, who served as a course marshal in Central Park. “As I walked up, I heard one of them say they couldn’t get a pulse.”

With Shay’s heart apparently stopped, Weaver, a former emergency medical technician, and two others performed CPR. Paramedics responding to a 911 call arrived approximately six minutes later, according to a spokesman for the New York Fire Department, which receives such calls. (Eight ambulances were in or near the park for the race.) The paramedics tried to revive Shay with a defibrillator and by pumping oxygen into his lungs. After about seven minutes, Shay was taken to Lenox Hill Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 8:46 a.m.

Leading up to the Trials, the 28-year-old runner had shown no apparent signs of distress. His wife, Alicia, says blood tests taken weeks prior indicated his physical condition was normal. Joe Shay, Ryan’s father, says his son recently had complained of fatigue and dizziness and had lost weight (from 155 pounds down to 147), but his training was unaffected.

Then why would a supremely fit athlete suffer an apparent cardiac arrest at the peak of his career? An autopsy report released one day after Shay’s death proved inconclusive. Subsequent tests, including a toxicology screen, were incomplete at press time.

Shortly after Ryan’s death, Joe Shay said his son had an enlarged heart, which doctors had first observed when he was 14. But Barry Maron, a cardiologist who has studied sudden death among athletes, says a modestly enlarged heart can simply be the product of conditioning and not a sign of impending medical danger.

Joe Shay also requested the toxicology screen, wanting to quell any possible suspicion that his son had used performance-enhancing drugs. “I can’t even fathom that he would have taken anything at all,” Shay says. “He was so against using drugs.”

For her part, Alicia Shay looks forward to one day knowing the cause of Ryan’s death, but says, “It wouldn’t change my life. It wouldn’t give me my husband back.”-Susan Rinkunas

Wharton arrived just as EMTs and paramedics were pushing Ryan’s stretcher into an ambulance and closing the doors behind him. He spotted a woman visibly upset. “She said she was a physician but not associated with the race,” Wharton recalls. “She had tears in her eyes. She said she had been giving him CPR for eight minutes, but couldn’t revive him.”

As the ambulance pulled away, Wharton called Alicia. “They’re taking Ryan to Lenox Hill Hospital,” he said. “I’ll meet you there.”

Alicia asked a policeman for directions, and now she was truly glad to be wearing those racing flats. She tore across a small greensward, exited the park just north of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and flew across Fifth Avenue after a quick traffic check. She turned south on Park Avenue and converged with Wharton on opposite sides of 77th Street, just a block from the hospital. It probably took her just six or seven minutes to get there from Central Park. At the main desk, she asked where Ryan was, and just kept moving.

She got to the room, but something seemed amiss. There was too much commotion. “It was chaos,” she recalls. Doctors flitted about frantically. She couldn’t see Ryan, and figured she must be in the wrong place. To be sure, she pushed through to sneak a look. It was Ryan. Someone was working over his chest.

A doctor led her from the room and explained that Ryan’s heart had stopped beating. They couldn’t get it restarted. The words didn’t sink in. They made no sense. No heart beat? How could that be? Ryan had a head injury. Even if it were true, she had heard so many stories and seen so many TV shows. Those defibrillator paddles, they always got the job done. “I didn’t believe the doctor,” she says. “I figured he was one of those people who always assumes the worst. I knew Ryan was going to be okay.”

She waited for the good news. It never came. A few minutes later, one of the doctors said, “I’m sorry, there’s nothing more we can do.”

The room slowly emptied. Alicia had Ryan to herself. For an hour, maybe more, she held his hand the way he had held hers the night before. She expected him to open his eyes any minute. She hugged him and waited for him to start breathing again. “I was convinced he would,” she says. “I knew he would. He felt so alive. He was so warm. It was as if we were lying in bed holding on to each other.”

AT THE END OF NOVEMBER, ALICIA SHAY RETURNED TO THE HOME IN FLAGSTAFF SHE HAD SHARED WITH RYAN. Friends and family members had warned her not to. She admitted to being “so scared” the first time back. Then she realized that she felt more comfortable in Flagstaff than anywhere else, with all their mutual friends and the places they frequented and the reminders of Ryan throughout the house.

Lauren Fleshman, her former teammate at Stanford, was coming for the month of December. Sara and Ryan Hall, who ended up winning the Olympic Trials, planned to visit in January. And there would be others after them. “It’s going to be a very full house,” she says with a hint of laughter. “I don’t have enough beds for everyone.”

There’s a brief pause. It has been nearly one month since the morning that her husband died. Then she continues. “I’m doing okay,” she says. “Nothing can take away the pain I feel over Ryan’s loss, and I know someone else might be filled with anger, but I’m 100 percent amazed every day by the Lord’s grace, power, and love. And I’m so thankful for my amazing family and all my friends.”

Alicia then talks about her own running and her future. She says she gives Ryan credit for her comeback and strong performances in 2007. “He knew how much I loved running, and he wouldn’t let me quit, even when I was very down,” she says. “He was my best friend and my number-one fan.”

She wants to keep running, and to pursue her dream, the same as Ryan’s: to make the U.S. Olympic team that will compete in Beijing this August. “That’s what he would have expected. I can’t expect anything less of myself. I won’t expect anything less.”

Alicia will race the 10,000 meters at the U.S. Olympic Track Trials in Eugene, Oregon, on Friday evening, June 27. She’ll be running on Pre’s track, the one where Ryan scored his biggest track victory in 2001. The symmetry is too perfect. But it’s a brutal system, the Trials: one day, one race, one woman against the distance. Nothing is guaranteed. Nothing. In last summer’s national championships, Alicia finished fourth. She’ll have to move up at least one position. And because of what happened to Ryan at the Marathon Trials, the whole world will be watching. That’s a lot of pressure.

“After what I’ve just been through, pressure is nothing,” she says. “Other peoples’ expectations mean nothing to me. I have my resolve-that’s the important thing. And I have Ryan’s passion. He believed racing should be joyful, and so do I. The only hard thing will be running my race without having Ryan there.”

She sounds resolute, if a bit shaken, much like the last time many people saw her. That was at Ryan’s funeral, two weeks earlier in Central Lake. In the evenings leading up to the funeral, Quinn Barry and several others had organized a series of memorial runs around the Central Lake High track, which was ringed with flickering luminarias. You didn’t have to run. You could walk. You could just show up and bow your head. “I knew that people would want a place where they could come to remember Ryan,” said Barry.

For four nights, they came. Friends. Family. Old classmates. Current Central Lake students. Coaches who knew and admired Joe and Susan Shay and their years of devotion to youth track. Townsfolk who didn’t know Ryan or any of the Shays, but had heard the stories and understood the loss, not just to the immediate family, but to every small town where big dreams are too easily punctured.

On Thursday night, the night of the final run, a thick rain and mid-30s temperatures couldn’t keep nearly 200 people from paying their respects. Roger Send and his daughter Amanda, 17, drove from Traverse City, 40 miles to the south. They had met Ryan at a cross-country race the previous year. “He told me how to use energy gels to improve my endurance,” said Amanda. “And he said I should never let anyone discourage me about my running. I should always stay positive and focused.” The Sends knew that Ryan had fallen at the 5.5-mile mark in Central Park, and they had decided to finish his marathon for him by logging 20.7 miles on the Central Lake track. It took them nearly four hours, but they reached their goal.

On Sunday, eight days after the Olympic Trials, Ryan Shay was laid to rest after a packed memorial service at the Harvest Barn Church. Ryan and Alicia had been there several times and enjoyed its rousing, 10-person instrumental-and-vocal praise band. The service lasted almost three hours, and included eulogies from three important Joes in Ryan’s life: Joe Piane, his Notre Dame coach; Joe Vigil, his professional coach; and Joe Shay. Speaking in a soft, tremulous voice, Joe Shay told the congregation that his son was a tough, determined man, “but I prefer to think of him in words such as tender, loving, sincere, caring, and loyal.”

As the service was about to end, the church band prepared to play a final song, “Blessed Be Your Name.” The minister looked down at Alicia to ask if she wanted the original, upbeat version. Or, given the somber circumstances, would she prefer a “calmer” version?

Alicia didn’t hesitate. She made the only choice possible. Up tempo.

Story Update · October 27, 2016

“The reason I think Ryan Shay’s memory lives on is that he wasn’t the most talented runner out there; he wasn’t Meb or Abdi or Dathan or Ryan Hall,” says Amby Burfoot. “But he worked at it so hard and so assiduously and loved the sport so much.” Shay's legacy lives on in his home state of Michigan. A year after their son's death, Shay’s parents established a memorial scholarship in his name at Central Lake High School. The Ryan Shay Midsummer Night’s Run has raised money for the fund over the last eight years and has become a Fourth of July tradition in his hometown. His high school also puts on the Ryan Shay Memorial cross-country invitational, and the town of Charlevoix, Michigan, has hosted a Ryan Shay Mile since 2008. In tribute to his brother, Stephan Shay ran the 2014 NYC Marathon at age 28, the same age Ryan was when he died; he finished in 2:19:47. After her husband’s death, a series of injuries kept Alicia Shay away from racing until 2012, when she won the TransRockies three-day trail race. She still lives in Flagstaff and continues to compete in trail and mountain racing while operating an online coaching business. Earlier this year, she married Chris Vargo, whom she met through the local running scene. “It’s been over eight years, but it’s still very fresh for me,” she says. “I struggle with it every day, but I’m really grateful to be where I am in Flagstaff, to have this community, and that I met Chris and found something special with him. When you lose someone, it doesn’t get better with time, you just have to choose to fill your life with other great things.” –Nick Weldon

('You Might Also Like',)