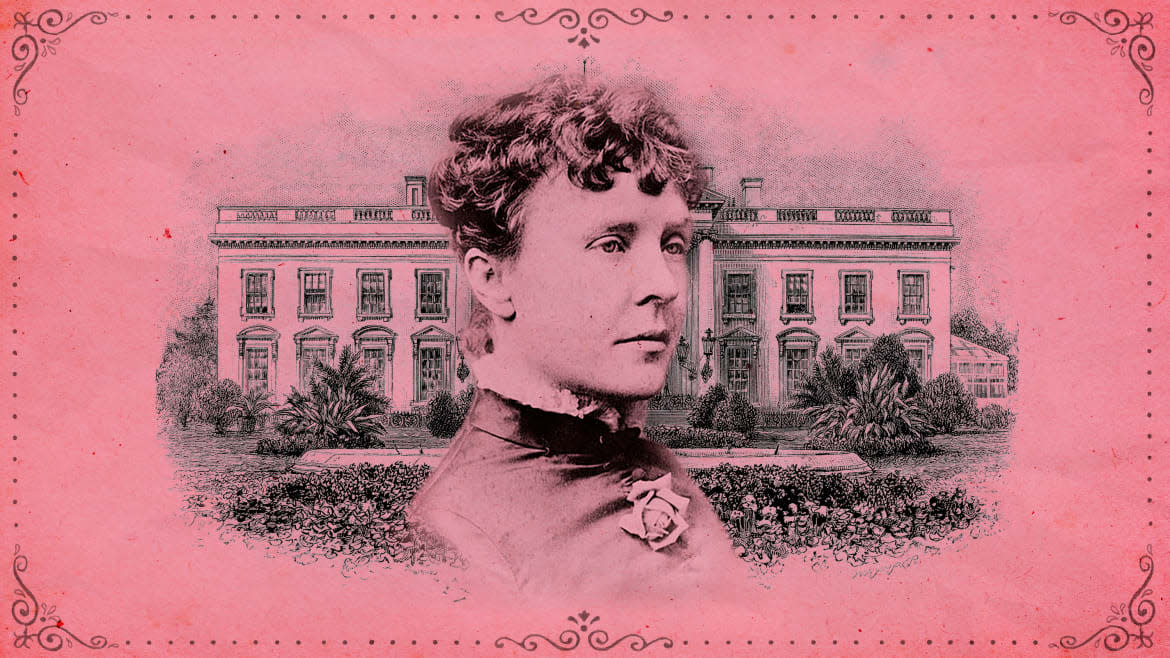

The Private Passions of Rose Cleveland, The Lesbian First Lady of The White House

If Pete Buttigieg is elected president he would become the first out-gay president, the first not-out gay president being, in all probability, James Buchanan (1857-1861).

Chasten Buttigieg, Mayor Pete’s husband and ace social media practitioner, would become America's first out-gay First Gentleman.

The White House has already housed at least two First Ladies who loved women. Eleanor Roosevelt's long relationship with journalist Lorena Hickock was the subject of Susan Quinn’s 2016 book, Eleanor and Hick: The Love Affair That Shaped a First Lady.

And then there was Rose Cleveland.

Rose Cleveland was Grover Cleveland’s youngest sister, and when Cleveland was elected president in 1884, he became America’s second bachelor president, after Buchanan.

Cleveland—whose biography I researched and wrote—required a White House hostess, and he named Rose to the position. Rose was thirty-eight and unmarried. Rose moved into a bedroom on the second floor of the White House. Washington got its first real look at her on the night of the inaugural ball.

As First Lady, she should have been the center of social attention, but in reporting on the evening’s activities the Washington Post awarded fashion accolades to the wife of the Vice President, following by the wife of the commanding general of the United States, followed by President Cleveland’s three nieces, his sister, Mary, and finally First Lady Rose, whose white silk gown was depicted without editorial comment.

Four days later, Rose held an official reception. She stood in the East Room greeting a throng of high-society ladies.

The rumor mills started churning. Rose wore her coiled hair short and sensible, although the Washington Post was quick to point out that “there is nothing mannish” about her.

Rose invited a delegation from the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union to tea. This was bold of her: The Prohibition Party had fielded a candidate against her brother in the election of 1884.

Rose drank only water at dinner. She also let it be known to the president that in her opinion he was appointing too many Catholics to high-level positions in the administration—a position Cleveland found “annoying.”

In mid-March, Rose had company at the White House. A woman she knew from Albany, Miss Annie Van Vechten, arrived for an extended stay. Annie was a forty-year-old brunette from a distinguished Dutch-American family.

She assisted Rose in hosting an afternoon tea and attended Sunday services with Rose at the First Presbyterian Church. No one really knew what to make of Annie. Was she Rose’s companion? Or was this a cover and was President Cleveland courting her?

When Annie finally departed the White House in mid-April, Rose apparently sank into a state of melancholia. Some of the formal activities required of her as First Lady were, in her estimation, nonsensical. Conversely, some of the upper-crust ladies she came in contact with found Rose “rather terrifying.”

Like her brother, Rose had an extraordinary capacity for near total recall. It was said that she could conjugate ancient Greek verbs in her head—a skill that was to come in handy in Washington when she found herself passing time on tedious reception lines.

Only two months into her time at the White House, Rose scaled back her First Lady duties and cancelled all White House receptions for the remainder of the social season. She left Washington for New York, for rest and recuperation. In a letter to another sister, Mary, President Cleveland wrote of Rose: “She’d had a pretty hard time here.”

Rose’s days as First Lady came to an end on the evening of June 2, 1886, when President Cleveland married Frances Folsom in the Blue Room of the White House.

Frances was twenty-seven years younger than the bachelor president. Cleveland had known Frances since she was a baby. Her father, Oscar Folsom—Cleveland’s best friend—had lost his life in a buggy accident when Frances was nine, and Cleveland became Frances’ de facto legal guardian who was consulted on all important aspects of her upbringing. Imagine the uproar if such a White House marriage were to take place today.

Rose moved out of the White House. Her time as First Lady had lasted fourteen months. She departed Washington as she had arrived—an enigma.

Rose returned to the humble Cleveland family cottage in Holland Patent, New York, wrote a novel (the rich and “haughty” protagonist was said to be modeled on Frances Folsom), and taught history at an all-girls school in Manhattan.

In 1889, Rose met the love of her life. She was vacationing in Naples, Florida, when another guest checked into the hotel. Evangeline Marrs Simpson was the beguiling young widow of a millionaire merchant from Boston. The private correspondence between the women lays bare one of the great forbidden romances of the Victorian Age.

Ah, Eve, Eve, surely you cannot realize what you are to me…

Oh, Eve, Eve, this is love itself…I love you, love you beyond belief—you are the world to me.

You are mine, and I am yours, and we are one.

Gazing at Evangeline’s photograph one day, Rose wrote that she could not take her eyes away—“the look of it making me wild.”

Rose lived to the age of seventy-two. She and Evangeline were living in Tuscany when the great flu epidemic of 1918 swept through the village of Bagni di Lucca on its way to killing 55 million people worldwide. Rose and Evangeline organized the village’s medical response. Rose also cabled her friends in America to send money and medicine.

Rose died six days after she was stricken with fever. By edict of the village mayor, all shops and places of business were closed and flags flown at half-mast in Rose’s honor. When Evangeline died in 1930, she was buried in a grave next to Rose, in a cemetery on the banks of the Lima River.

Rose’s letters to Evangeline remained sealed for fifty years, as stipulated In Evangeline’s will. They can be found today in the archives of the Minnesota Historical Society.