Private Equity’s Massive UK Debt Binge Sparks Warnings of Danger

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- For an idea of what private equity ownership can mean for ordinary people, UK grocers are a good place to start. Both Wm Morrison Supermarkets Ltd. and Asda have been laboring lately under giant debt burdens put on their shoulders by the financiers who bought them in 2021.

Most Read from Bloomberg

One Dead After Singapore Air Flight Hit By Severe Turbulence

ASML, TSMC Can Disable Chip Machines If China Invades Taiwan

Hims Debuts $199 Weight-Loss Shots at 85% Discount to Wegovy

‘It Felt Like We Had Crashed,’ a Singapore Air Passenger Recalls

Tesla Shareholder Group Slams Elon Musk’s $56 Billion Pay Package

With the cost of servicing all that debt beginning to spiral, it’s not only the owners who have cause to worry. British lawmakers have hauled in Asda’s backers, including one of the tycoon Issa brothers and PE firm TDR Capital, at various points to grill them on everything from not passing lower petrol prices on to shoppers to the complexities of its corporate structure.

Uppermost — for Morrisons, Asda and the host of UK companies now in private hands — are questions about coping with higher interest rates. The Bank of England has become worried enough about potential economic threats that it’s started probing PE giants and their businesses to assess their resilience.

Corporate Britain’s increased dependency on debt over the past few years creates “big new risks to systemically important employers, not only for jobs but for taxpayers,” says Liam Byrne, a former Labour Treasury minister who chairs Parliament’s business and trade committee. “There are four to five highly leveraged general retailers like Morrisons and Asda, companies employing hundreds of thousands of people, owned by private equity firms that are taking risks in the dark. That’s a dangerous place for UK capitalism to be.”

Morrisons and Asda counter that they’ve spent heavily on their businesses and are cutting “leverage” (indebtedness), the former by selling assets. Morrisons also plans to buy back up to £1 billion of bonds and loans as part of a debt-reduction plan. Asda has just refinanced billions of pounds of loans, showing “confidence in the underlying strength of the business,” according to finance director Michael Gleeson. But its interest rate has doubled on some debt.

“Since the shareholder group acquired the business in June 2021, they’ve invested more than £3.5bn,” an Asda spokesperson says. “As a highly cash generative business, it will comfortably be able to meet its financing costs.”

Hungry Times

While grocers have become something of a rallying point for British policymakers disturbed by what PE ownership means for UK Plc, they’re far from alone. US buyout groups especially have flocked to the country in recent years in the hunt for “Brexit bargains,” so called because targets suddenly became much cheaper after the pound plummeted against the dollar.

From pubs and gyms to Madame Tussauds, every kind of consumer business was fair game. The bet was that while these were often low-margin companies, they tended to own lots of buildings, and knockdown prices and near-zero interest rates made them look like surefire winners. Many were piled up with debt to pay for the splurge, pushing the amount of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds issued by UK companies to a record £200 billion plus, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

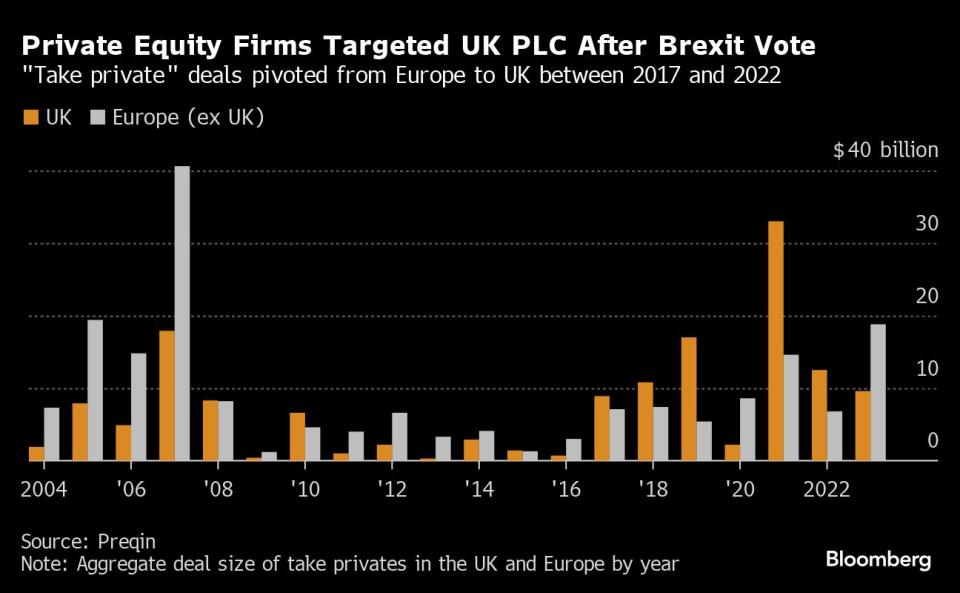

The PE industry has “eaten up” British companies, says Mark Remington, a portfolio manager at EFG Asset Management, in comments that bring to mind a German politician’s famous description of buyout firms as “locusts” back in the 2000s. In the five years after the Brexit vote, the number of UK “take private” deals outstripped the whole of the rest of Europe, barring Covid-hit 2020. That feasting has helped load more debt than ever onto the nation’s businesses.

Now the UK is dealing with the hangover. “There’s nothing wrong with a bit of private equity investment,” Remington says. “But it’s wrong when they lever businesses to the hilt with no path forward.”

The forthcoming general election, which must take place before January, will be another battleground for a buyout industry that’s trying gamely to protect its gains and argue for its utility. The opposition Labour Party, strong favorite to win power, is promising to jack up taxes on “carry,” the profit share that incentivizes buyout financiers to make outsized bets.

But politicians are in a quandary: Crack down too sharply and they could deter desperately needed UK investment at a time when the country’s public markets are moribund. Go too easy and the government may end up having to cover salary and redundancy costs if a company gets into trouble.

Defenders of the buyout firms argue that borrowed money is often earmarked for spending and acquisitions, as at Morrisons, which has snapped up convenience shops, and Asda, which has expanded to 1,200 sites from 633 stores nearly three years ago. And corporate bosses do sometimes welcome the smack of harder-edged financial owners. John Colley, a professor at Warwick Business School, says PE is “quite unlike” publicly listed companies, where “half the non-executives know nothing about the industry.”

Nonetheless, the financial environment for many PE-owned companies is getting tougher. Asda has refinanced some of the borrowing used to fuel its purchase by TDR and the Issas, who first made their fortunes in gas stations. The new debt priced at yields well above 7% this month, compared to existing coupons of 3.25% and 4.5%. Fitch reckons that will take Asda’s interest bill up to £390 million in 2025, about a third of this year’s projected earnings.

The situation for Morrisons is worse. It was purchased by Clayton Dubilier & Rice in 2021 in a deal where the firm piled billions of pounds of debt onto the business. Morrisons posted a £1.1 billion pretax loss in the year to Oct. 29 2023, according to a Companies House filing by its parent Market Topco. That included £735 million of finance costs such as interest payments.

Gunjan Dixit, a senior credit officer at Moody’s Ratings, is expecting Morrisons to cut its debt using cash from a recent £2.5 billion sale of petrol forecourts. But the retail backdrop isn’t getting easier. Competition among UK grocers remains fierce and consumer confidence weak, she adds.

Creaky Business

As well as supermarkets, buyout firms have snapped up consumer-serving assets that include anything from Britain’s biggest pub chain Stonegate to fitness centers PureGym and David Lloyd; and from the London Eye to posh baker Gail’s and the owner of urban coffee shops Notes.

Some businesses such as Gail’s are doing well, but a few are creaking. Debenhams, a department store chain that suffered for years after it was loaded with debt, before ultimately going bust, remains a cautionary tale.

A particular problem is that many loans used to finance more recent buyouts were done at a floating rate, meaning companies are paying interest rates they’d never have dreamed of. The owner of Notes, backed by CD&R, has a loan maturing in March 2026 that was priced at 500 basis points over sterling Libor in 2019, translating to about 5.8%. That interest is above 10% today because of the move in the underlying rate. The company recently refinanced at an even wider spread of 550 bps, pushing the yield to 11%.

The floating-rate issue may partly explain the jump in “default rates on leveraged loans” noted in the record of the BoE financial policy committee’s March meeting — and why the central bank sees evidence of some company valuations coming “under pressure.”

TDR-owned Stonegate is also going through difficult creditor talks as a £2 billion-plus debt wall looms in 2025. Asda and Morrisons have debt maturities further down the line, giving them breathing space.

One concern for politicians is that taxpayers can end up on the hook if a company goes bust. In a recent example, The Body Shop’s new private equity owner put the UK stalwart into administration mere months after buying it. German firm Aurelius hadn’t saddled the company with debt, but the move did prompt British lawmakers to write to the Insolvency Service to ask how much the redundancies were costing the state.

For some firms that did leverage acquisitions to the max, higher base rates have been a nasty surprise. As Covid eased, consumer companies and especially supermarkets were seen as slam-dunk investments that shoppers would always need. “They were boring businesses with low margins but the idea was that they’d be able to withstand a lot of debt,” says Hugo Squire, high-yield portfolio manager at Schroders. “Higher for longer destroyed that trade,” he adds, referring to central bankers’ caution about changing monetary course.

Cutthroat competition and runaway inflation have stung as well.

In fairness, private equity does bring needed investment into the UK. And its practitioners argue that it’s wrong to get too hung up on even extended periods of trouble when the real benefit of private markets is that investors can take a longer-term view than for volatile publicly traded assets.

“In the last four years, we've had a recession, inflation, supply chain issues, the war in Ukraine and generally a shocking amount of disruption, including rate hikes,” says Nigel Walder, a partner at Bain Capital, owner of PizzaExpress and Gail’s, adding that pulling though the turmoil will be “testament to the enduring resilience of private equity, and the value that comes from being able to choose when to realize your asset."

In addition, there have been no major initial public offerings on the London Stock Exchange this year so far, despite a revival elsewhere on the continent. Private money’s often the only show in town when hunting corporate finance.

“Private capital has been an important contributor to UK economic growth for more than 40 years,” says Michael Moore, chief executive of the British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association. When being grilled by Byrne’s committee, TDR highlighted its own record as an “incredibly long term” investor.

Still, how firms reward themselves and what good they do to UK Plc will be argued over furiously this year as an avowedly pro-business Labour Party readies for power. Workers at supermarkets such as Asda and Morrisons have voted to strike at some stores recently, as union bosses complain of increased stress, pension changes and shabbier stores.

If rate cuts are delayed or don’t happen quickly, scrutiny will deepen. “There are big incentives in private equity to gear up these businesses to the hilt, both at a corporate and personal level,” says Byrne. “The downside risk is covered by the taxpayer.”

--With assistance from Sabah Meddings.

(Updates with Morrisons buyback in fifth paragraph.)

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

A Hidden Variable in the Presidential Race: Fears of ‘Trump Forever’

Millennium Covets Citadel-Size Commodities Gains, Just Not the Risk

Netflix Had a Password-Sharing Problem. Greg Peters Fixed It

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.