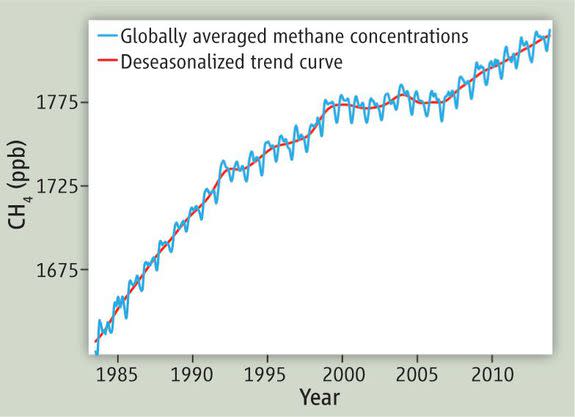

This powerful greenhouse gas has been rising sharply for a decade. Now we know why

Just over a decade ago, scientists found that methane — a potent greenhouse gas — had begun to rapidly increase in our atmosphere. The amounts of gas leaking into the sky has risen each year since, and there are two obvious candidates for this surge: Either the release of methane from the oil and gas industry, or naturally released methane from the world’s tropical swamps and marshes.

But when researchers did the math, things didn’t add up.

SEE ALSO: We are creating a new class of extreme weather events, with dire results

The amount of methane in the Earth’s atmosphere has been increasing by around 25 teragrams each year since 2006 — which, NASA notes, is about the weight of a whopping 425,000 elephants (seriously). Yet, when scientists calculated the likely estimates of both methane from the gas industry or marshes, their numbers were way overblown, vastly exceeding the 25 teragrams being added each year. So for ten years, there’s been a bonafide methane mystery.

Now, however, the mystery has likely been solved, and it turns out the methane comes from another source.

A group of atmospheric scientists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and other research institutions looked at satellite data showing that the amount of land burned globally by fires had been dropping during this period.

Their research, published this week in the journal Nature Communications, illustrates that this decrease in burned vegetation resulted in a notable drop in methane being released — enough to make the global methane numbers sink down to the measurement of 25 teragrams in Earth's atmosphere.

“There is agreement there is a puzzle and this likely solves this particular puzzle,” said NASA atmospheric scientist John Worden in an interview. Worden is also the study’s lead author.

“What we show is that there has been a larger than expected decline in methane from fires,” said Worden.

Specifically, this decrease in fire-born methane emissions was twice as much than researchers anticipated. Worden and his team measured the distinct fingerprint of methane from burning vegetation using NASA’s Terra and Aura satellites.

Image: LA Times via Getty Images

For a decade, scientists not involved with this NASA-led study were equally puzzled by the sources of this greenhouse gas surge.

"Yes, this was a significant puzzle and conundrum that had emerged in atmospheric data," said Penn State University atmospheric scientist Ken Davis in an interview.

"There's been a ping-pong game of explanations going back and forth about what might explain this," he said, referencing the earlier studies that suggested tropical marshes and rice paddies could be contributing more methane, while other studies pointed to the oil and gas industry.

But this decline in global wildfires seems to settle matters, for now. "It's a complicated puzzle with a lot of parts," said Davis, "but [the study's conclusions] do seem plausible and likely."

There are still regions in the world that experience heavy fire activity, specifically areas like central Africa. Here, farmers deliberately set blazes to kill off unwanted plants and to enrich the soil with the nutrients from burned vegetation.

But on a global scale, fire activity — and the associated methane releases from this burning — has been dropping.

Image: noaa

Although methane from fires has dropped off, the study suggests that just the opposite is occurring for methane released from swamps and human fossil fuel activity. "This argues that both of [these sources] have increased significantly between 2008 and 2014," said Davis.

Methane, like the carbon dioxide released from coal power plants and gas-powered cars, traps incoming and outgoing solar radiation and warms the planet. Methane is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, though it remains in the atmosphere for a far shorter period, on the order of several decades.

“Methane is an important greenhouse gas because per molecule it is 20 to 30 times more potent than a molecule of carbon dioxide for absorbing infrared radiation," Worden said. This means there's greater potential for increased trapping of radiation on Earth, and accordingly, more warming. The consequences of a warmer Earth are known and already being experienced today — such as extreme weather events — but at least this research clarifies where this potent greenhouse gas is coming from — and where it isn't.

"We care about what the cause is because we want to understand what's driving the climate system," said Davis.

WATCH: Californians band together to save horses from wildfires