Postage Stamps Overlook Earth's Tiny Creatures

What can postage stamps tell us about biodiversity conservation?

When Andr? Nem?sio isn't studying biology, he collects stamps. Andr? and his colleagues Diana Seixas and Heraldo Vasconcelos recently cataloged the animals represented on hundreds of thousands of postage stamps for sale on Delcampe and eBay. They found that 60% of stamps feature birds or mammals, even though birds and mammals represent less than 1% of all known animals. If someone studied the diversity of life through stamps," Andr? told me, "he or she would reach the conclusion that birds and mammals are the dominant species on earth, that elephants are perhaps the most abundant creatures on this planet, and that insects are a small fraction of nature, mainly represented by butterflies."

Why does it matter which animals make it onto our Valentine's Day envelopes? Andr? and his co-authors argue that conservationists could use stamps to teach others about the diversity of life. "If people only know birds and mammals, they will only care about them," Andr? explains. "Just telling people that there are 'hundreds of thousands' of beneficial insects in nature is not enough. Numbers will not catch people. We must show them this huge diversity of life."

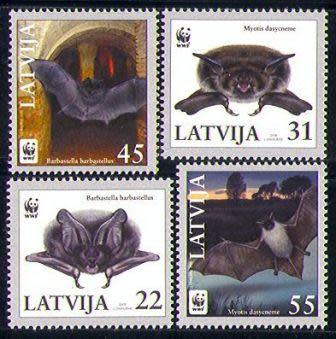

Apparently invertebrates make for rare stamps, as do reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Among mammals, perissodactyls (like horses, rhinoceroses) and proboscideans (like elephants) are 57 and 79 times more frequently represented than would be expected by their actual occurrence, whereas rodents and bats are 13 and 22 times less represented than expected.

For years conservation biologists have debated whether "flagship species" like tigers, pandas, and dolphins help or hinder conservation efforts. Some believe that flagship species raise environmental awareness, and that protection of a flagship species is cost effective because, by protecting that species' habitat, other species will also benefit. Others argue that an emphasis on flagship species is disingenuous in a world of approximately 8.7 million species, and that a focus on the few leaves little resources for other species.

Many small species do important things. Pollinators, for example, make it possible for us to eat. And weird, lumpy, ugly species are cool. I, for one, would like to continue to live in a world with Andean cock-of-the-rocks and glass frogs and myxogastrids and flanged bombardier beetles. (They'd make killer stamps, too.)

Conservationists have said for the past 20 years, "ecosystem services are vital to human well-being" and "biodiversity promotes ecological resilience" and "management practices should account for ecological and social processes." But there's another way to pitch conservation: Species are wondrous, beautiful, astonishing. Species have stories worth hearing. Do we really have the right to write off species as creepy or slimy? We're pretty creepy and slimy, too.

Other species are similar to us and different than us at the same time. They are here, for now. Let us celebrate them. Let us put them on stamps.

Images: Bat stamps: eBay; Glass frog: Heidi and Hans-Jurgen Koch.

Follow Scientific American on Twitter @SciAm and @SciamBlogs. Visit ScientificAmerican.com for the latest in science, health and technology news.

© 2013 ScientificAmerican.com. All rights reserved.