Possible dissent hangs over Fed's first rate cut in a decade

By Ann Saphir and Trevor Hunnicutt

WASHINGTON/NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. Federal Reserve policymakers will not surprise markets if they deliver on expectations and cut U.S. interest rates for the first time in a decade on Wednesday.

Less clear is how Fed Chairman Jerome Powell will manage debate at the central bank about whether the stimulus is necessary. The Fed chief faces a strong possibility that the move will draw at least one dissent.

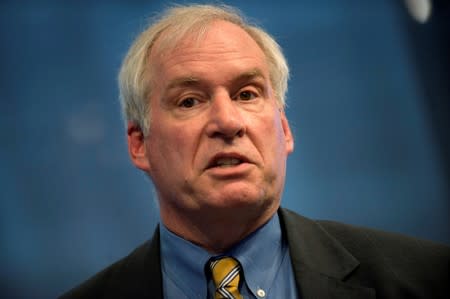

Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren, one of two current policymakers who was present when the Fed last initiated a rate-cutting cycle nearly 12 years ago, earlier this month said he does not want to ease policy "if the economy is doing perfectly well without that easing," adding in a CNBC interview that the state of the U.S. economy is "quite reasonable."

Rosengren, along with Chicago Fed President Charles Evans, voted in favor of a half-percentage-point rate cut in September 2007, which proved to be the first of 10 cuts that would eventually take the federal funds rate to near zero.

If Rosengren objects this time, though, he may not be alone. Kansas City Fed President Esther George may also vote against a rate cut. In recent remarks, she said monetary policy is "in a good range," though she is "prepared to adjust those views" should downside risks materialize.

Rosengren and George are among the 10 people with a vote on rates on Wednesday, and they could shake up the Fed's normally consensus-driven approach. If both policymakers dissent, that would make the onset of this rate-cutting cycle more controversial than any of the Fed's last four.

In three of them - 2007, 2001 and 1998 - the votes to lower rates for the first time in a cycle were unanimous. In 1995, George's predecessor at the Kansas City Fed, Thomas Hoenig, was the sole one to dissent.

With Powell already under attack by U.S. President Donald Trump for not doing enough to boost the economy, he could find his job even more difficult if either or both vote no. The Fed is due to release its policy statement at 2 p.m. EDT (1800 GMT) on Wednesday, and Powell will hold a press conference shortly after.

Powell may want to nod to dissenters' concerns and signal that this may not be the first in a long series of cuts, or he may want to counteract the dissents and strongly reinforce a "dovish" Fed outlook, meaning one more biased to cutting rates than a "hawkish" stance.

"We believe that Fed Chair Powell will want to counter the hawkish message sent from dissents," Bank of America economists wrote in a note on Friday. "We therefore think it will leave Powell to be even more dovish in the press conference."

Neither dissent is a sure thing. Fed policymakers often express reservations ahead of meetings without following through with a dissent, sometimes finding themselves convinced by colleagues over two days of talks. Powell stoked expectations of a rate cut in recent weeks, citing the U.S.-China trade war, a global economic slowdown and tame inflation as growing risks.

The fact that there is even any question about a dissent from George, once among the Fed's most hawkish members, is a sign of how much the economy has changed in recent years.

'MORE DOVISH'

George is not shy about speaking up. In 2013, she dissented seven times because of worries the Fed's "aggressive" bond-buying would fuel unwanted inflation. Only at the year's last policy meeting, when the Fed announced it would reduce the pace of its stimulative bond purchases, did she join the majority, despite misgivings over a new promise to keep rates low and her personal preference for a sharper tapering of that bond-buying.

The year ended with the unemployment rate at 6.7%; it is now 3.7%, while inflation by the Fed's preferred measure is still, at 1.8%, below the U.S. central bank's 2% annual target. Unemployment is near a 50-year low, consumer spending is surging, and the economy, despite a second-quarter slowdown, is still growing at a rate many economists regard as faster than sustainable.

The fact that such a situation does not trigger a number of dissents suggests the entire Fed has shifted, according to Crosby Kemper III, the executive director of the Kansas City Public Library and a former banker who touted George’s inflation-fighting credentials in a wide-ranging public interview with her in February.

"I would be a little surprised if she didn't resist a lower rate," said Kemper, whose great-grandfather helped convince the Fed to put one of its 12 outposts in Kansas City, Missouri, more than a century ago. But, he added, he can't be sure: "Everybody has gone squishy, not just Esther."

A dissent would go a long way to convincing investors the Fed hasn't forgotten about the threat posed by inflation, said University of Rochester economics professor Narayana Kocherlakota, who dissented several times when he was Minneapolis Fed president.

"I do hope that there is a dissent next week that goes on record as opposing the (Fed's expected) 25-basis-point cut," said Kocherlakota. "The Fed has become more 'dovish' - it seems more willing to court higher inflation in 2019 than in 2015, even though it's clearly doing better on the employment mandate."

(Reporting by Ann Saphir in Washington and Trevor Hunnicutt in New York; Editing by Dan Burns and Paul Simao)