Portraying journalists onscreen in the age of Trump

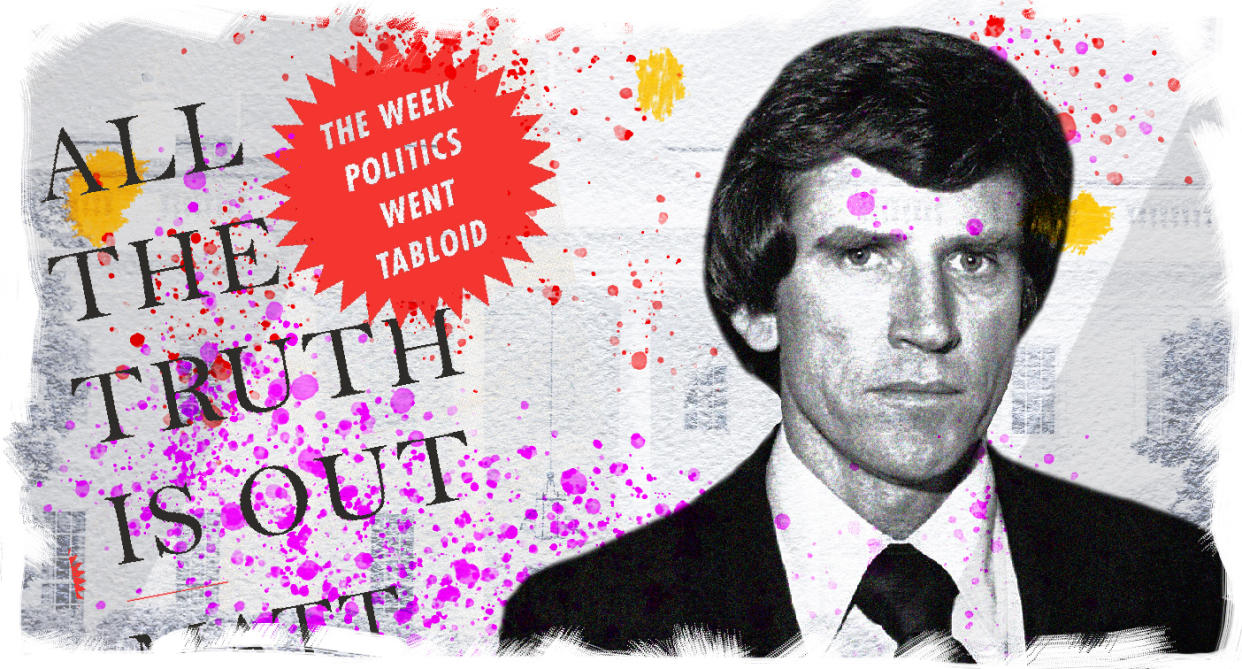

This weekend, a film called “The Front Runner” will open in about a dozen American cities. I helped write the movie, which is directed by Jason Reitman and stars the brilliant Hugh Jackman (in a non-singing, non-clawing role). It’s based on my 2014 book, originally titled “All the Truth Is Out.”

Readers of this column over the years will be at least passingly familiar with the storyline. “The Front Runner” tells the story of Gary Hart, whose promising presidential bid in 1987 was undone by a fast-moving, all-consuming sex scandal — the first of the satellite age.

Reporters from the Miami Herald questioned Hart in the alley behind his Washington, D.C., townhouse and wrote an exposé about a woman they’d seen inside it. Then a Washington Post reporter asked Hart on national television if he had ever cheated on his wife.

(I realize it might seem self-absorbed to write about your own film, but stay with me here, because I have something larger in mind than enticing you to see a movie. Although that would be fine.)

“The Front Runner” is, by design, morally complex and as messy as real life; it sets out not to exalt or blame anyone, or to impart some neatly distilled lesson, but rather to illuminate a moment that has reverberated for decades. That moment was brought on by a confluence of forces churning in the society, from the legacy of Watergate, to the rise of feminism, to the advent of the 24-hour news cycle and the evolution of tabloid TV.

This is a story told not just from Hart and his family’s perspective, but from the points of view of myriad characters caught up in the scandal — reporters, aides and, importantly, the woman whose reputation was destroyed, as well as other women degraded by the machinery of scandal. It’s a movie about well-intentioned people who found themselves faced with unfamiliar dilemmas and made the best decisions they could.

We’ve been showing the film at festivals for a few months now, and the responses have been mostly gratifying. Among some of my colleagues in journalism, though, there’s an almost reflexive irritation.

I guess there’s some concern that at a moment when all of us in the media are under unrelenting assault from a president who brands us as national traitors, a film presenting journalists as anything less than heroic strikes a discordant note.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Joe Morgenstern, a venerable critic whose work I’ve often admired, argued that both the book and the movie have “been overtaken by ominous events” in the country, and since the film doesn’t celebrate good journalism, it “may be enjoyable, but it isn’t helpful.”

As a filmmaker, of course, you’d always prefer to focus more on the art — you know, acting and directing and sound and costumes — than on how it might affect a national debate. Your job isn’t really to be helpful to anyone. It’s to grab the attention of an audience and make them think.

And in a movie where virtually all the characters live in a gray zone of morality, why should the journalists be somehow exempt? I count at least eight reporters and editors in the film who represent a range of perspectives on the scandal; it’s curious that some of my colleagues seem to identify only with the ones in the alleyway.

But look, as someone who’s covered five presidential campaigns, I understand as well as anyone the unease we feel right now, and the outrage at a president who berates and blacklists serious journalists. I, too, lose sleep over reckless rhetoric hurled from the White House podium and worry about what it portends.

And it seems to me this whole vein of criticism leads to some important questions for our industry right now, which are larger than any one movie.

If we’re not going to be branded as “enemies of the state,” then is it necessary to hold ourselves out as flawless guardians of democracy instead? Do we have to choose between defending ourselves from a demagogue, on one hand, and reckoning with our own role in having created him on the other?

Is it not possible to do both at the same time?

Because I’d argue that far from having been overtaken by events, both the film and the book from which it grew have been validated by them. And the issues they raise are more relevant than we’d probably like them to be.

“The Front Runner” depicts a time when the worlds of politics and entertainment suddenly collided. From that time on, our candidates would be treated like celebrities, with every facet of their inner lives — from the state of their marriages to the brands of their underwear — considered within the bounds of reasonable scrutiny.

And here’s the thing: When your process treats politicians like entertainers, you will inevitably get entertainers as candidates. It’s a process that attracts emotive performers and repels nuanced thinkers, that rewards shamelessness and discourages candor. It’s a process that takes you exactly to where we are today.

I and my co-writers (Reitman and Jay Carson, a political operative turned screenwriter) certainly didn’t set out to do anything quite that timely; we’d actually finished our script by the time Donald Trump was elected in 2016. But recent events have given the film an unsettling poignancy.

I can’t say if that’s a helpful thing right now. Of all the characters in the movie, I sympathize most with A.J. Parker, a reporter played by the young actor Mamoudou Athie, who’s trying to navigate a path between his ideals and his competitive instinct. We’re all walking that line all the time, as carefully as we can, and the last thing I’d want to do is make it easier for any politician — let alone a president — to portray us as callow or deceptive.

As a writer, though, I was taught I had a responsibility to reflect on the truth, rather than to calculate its impact on a cause. Even my own.

Journalists didn’t create the modern, entertainment-driven political process all by ourselves. As the film makes clear, there’s plenty of responsibility to go around — starting with candidates and extending to operatives and even to you, the voter. But we ask everyone else to be accountable for the consequences of their decisions, and I’ve never thought we had a right to ask less of ourselves.

Does having that conversation undermine the journalism establishment at a moment of crisis? I really don’t think so, and I’ll tell you why.

If Trump’s assault on the press resonates with some sizable plurality of the electorate, it’s because we’ve sometimes been careless with the public trust. We obsessed on trivialities and ratings, and spoke too glibly on cable TV, and generally treated politics like another form of “American Idol.”

And if we’re going to win back that trust, then we’re not going to get there by pretending we’ve always been the saintly figures portrayed in movies like “The Post.” We’re going to get there by having the courage to ask hard questions about our own role in creating the circus of contemporary politics.

There’s nothing treacherous about that.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

The CIA’s communications suffered a catastrophic compromise. It started in Iran.

Ending the Qatar blockade might be the price Saudi Arabia pays for Khashoggi’s murder

How Robert Mercer’s hedge fund profits from Trump’s hard-line immigration stance

Trump’s target audience for migrant caravan scare tactics: Women

Photos: Heartbreak in Northern and Southern California areas ravaged by wildfires