Polk water partnership is obtaining land rights for 61-mile pipeline, sometimes by court

The course of a future water supply in Polk County flows through the courthouse in Bartow.

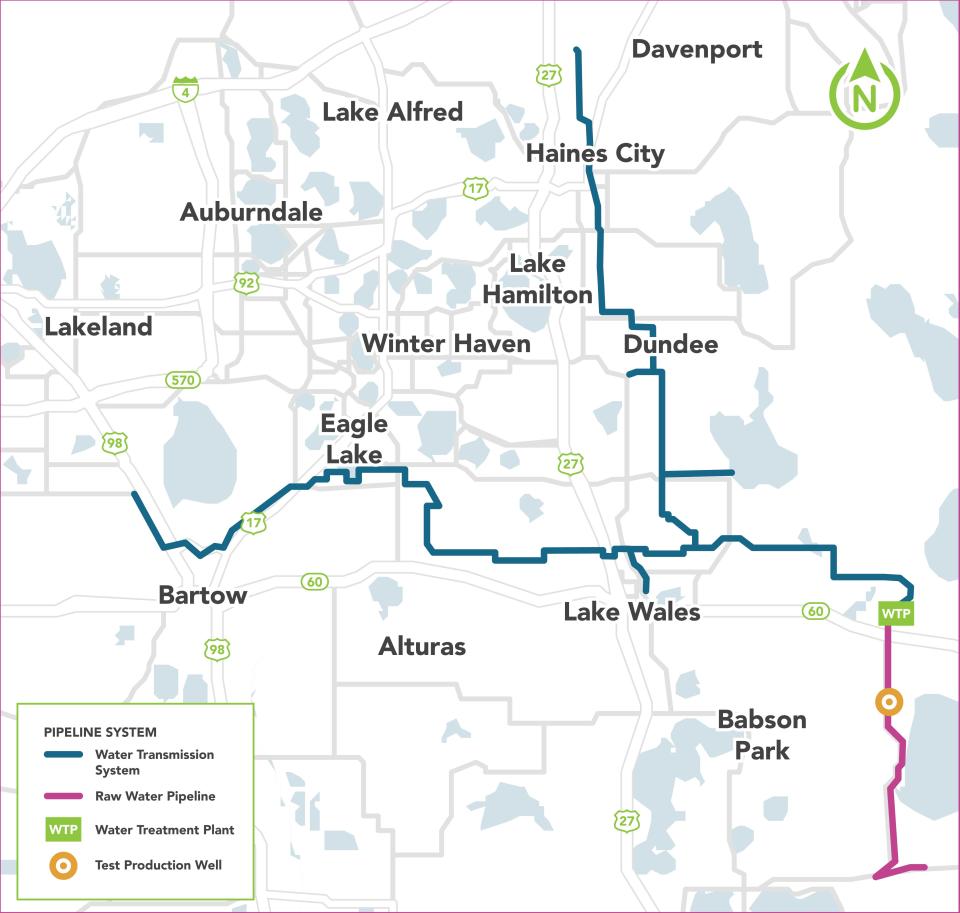

The Polk Regional Water Cooperative, a consortium of the county and local cities, has undertaken an ambitious project intended to ensure that residents will have sufficient water for the next few decades. The plan involves drilling wells into the lower Floridan Aquifer, much deeper than traditional wells, treating the briny liquid and then piping it over a 61-mile network to connect with existing utilities.

The drilling of two wells near Frostproof, the first phase of the Southeast Wellfield project, began in late 2022. The cooperative will oversee construction of a water treatment plant east of Lake Wales, and sustained work on the underground transmission lines could begin by early next year.

In the meantime, the cooperative is pursuing the necessary step of securing access to the land that the pipeline will cross. The project requires digging trenches to bury the pipes under some 300 privately owned parcels on the network’s course toward Lake Wales, where it will split into two lines headed to Bartow and the Davenport area.

American Acquisition Group, part of the cooperative’s consultant team, began contacting landowners last spring and making financial offers to cover the inconvenience of having the pipeline extended through their properties. Most of the time, the two sides reach agreements on the compensation and the property owners sign agreements, PRWC Executive Director Eric DeHaven said.

In some cases, though, landowners either disagree on the amount of money offered or refuse access to their land. When that happens, the cooperative turns to the courts, exercising its power of eminent domain, a legal concept that allows a government entity to take private property for public use and compensate the owners.

If a judge approves the cooperative’s eminent domain request, the two sides negotiate over the price for the easement. If they can’t agree on an amount, the case goes to a jury trial.

The Polk Regional Water Cooperative is not seeking ownership of the tracts in the planned path of the pipeline but instead seeks right-of-way easements, giving the cooperative access and permission to dig trenches and bury pipes.

The cooperative set aside $21 million for compensation to property owners for right-of-way easements needed to construct the pipeline, DeHaven said. The entire project has an estimated cost of $460 million.

Full-scale construction on the first segment of the pipeline could begin early next year, DeHaven said.

The cooperative also plans to drill a West Polk Wellfield and Water Supply Facility in the Lakeland area. The schedule for that project runs about 18 months behind that of the Southeast Wellfield.

Collaborative projects

The PRWC formed in 2017 in response to indications from the Southwest Florida Water Management District (known as Swiftmud) that it would begin limiting most withdrawals from the Upper Floridan Aquifer, the state’s main source of drinking water, to the levels needed to meet projected demands for 2025.

The cooperative arose from the Central Florida Water Initiative, a consortium of three water management districts, including Swiftmud, intended to promote regional water supplies. The districts warned that the region was nearing the limit for water that could be withdrawn from the Upper Floridan Aquifer without causing hydrological damage.

The PRWC comprises Polk County and 15 local cities. While most cities have committed to helping fund the deep well projects and will receive water, Fort Meade, Mulberry and Lake Wales are uncommitted project associates and Frostproof has no involvement. Swiftmud is the permitting authority and a funding partner.

Municipalities will make incrementally rising payments for participation in the Southeast Wellfield project. Polk County is expected to pay annual fees ranging from about $440,000 this year to $2.9 million in 2032, for a total of about $23.9 million.

Swiftmud has committed to reimbursing the member governments nearly $111 million for the Southeast Wellfield and about $76 million for the transmission system. Last year, the cooperative received confirmation of a $305 million federal loan, which will cover more than half of the anticipated costs of two deep-well projects.

The Florida Legislature is contributing funds through the Heartland Headwaters Protection and Sustainability Act, and the PRWC will draw money from Florida’s State Revolving Fund program and short-term commercial loans.

The Southeast Wellfield project will eventually include five wells and will ultimately generate as much as 12.5 million gallons of water a day, DeHaven said.

The transmission network will use steel pipes ranging in diameter from eight inches to 42 inches. The cooperative typically seeks an easement extending 40 feet from the edge of a property, incorporating the municipal right of way adjacent to a road, DeHaven said. The agreements often include an additional 10 feet for a temporary construction easement, he said.

The acquisition process begins with a notice to the property owner that the PRWC seeks an easement. An independent appraiser determines the value of the taking and any damages that might result from the construction, and the cooperative makes an offer to the owner.

As an example of a settlement made outside of court, DeHaven said the cooperative reached an agreement with Mountain Lake Corporation to run pipes along roads in Mountain Lake, a prestigious, private community in Lake Wales.

If no settlement is reached, the PRWC publishes public notices of its planned action before filing an eminent domain petition, something it began doing last May, starting with parcels nearest the well site, along Camp Mack Road and Mammoth Grove Road, east of Lake Wales. In legal terms, the cooperative sues the land owners for condemnation of the property. The first petition named four defendants, among them Duke Energy Florida and Pacific Life Insurance.

The cooperative also files a notice of “lis pendins,” or pending lawsuit, and a declaration of taking, which states the amounts it is offering to compensate property owners, based on an independent appraisal. The initial filing listed eight parcels, with compensation ranging from $3,750 to $48,700, based on the length of the needed easement.

Peterson & Myers, a Lakeland law firm, and Policastro Law Group, based in Clearwater, are handling negotiations for the cooperative.

In all the eminent domain hearings held so far, judges have ruled that the PRWC has the right to the parcels under Florida’s eminent domain law. Property owners rarely contest that, DeHaven said.

Property owner files appeal

For the first stretch of the pipeline, the affected properties have such corporate owners as Met Life Real Estate Lending and Hunt Bros. Inc., a citrus company, as well as owners of residential parcels.

The owners of Rolling Meadow Ranch Groves, owner of multiple parcels on Camp Mack Road, filed an appeal last month of the order of taking with Florida’s Sixth District Court of Appeal. The company asked the court to vacate Circuit Judge Ellen S. Masters’ order of taking for four parcels.

In an amended motion filed Feb. 26, the property owners wrote that they had “vehemently” objected to the taking, disputed that it was necessary for the project and said the cooperative had not considered an adjacent property owned by the Boy Scouts of America that was “more suitable, already cleared and approved for linear underground facilities.”

The Rolling Meadows motion claimed that doing so would yield potential savings to taxpayers of more than $1 million. The company's owner could not be reached.

The PWRC determined that rerouting the pipeline to the Boy Scouts property was not feasible. The tract serves as a federal mitigation site for the sand skink, a threatened species, and the cooperative would need to obtain permits from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Land owners often ask for the pipeline route to be moved to an adjacent property, DeHaven said.

“When you construct a pipeline like this, when you're looking at these road corridors, you look at the full road corridor as to which side of the road is going to be cheaper and easier to construct upon,” he said.

The motion also argues that hearings should have been delayed because Rolling Meadows’ lawyer was seriously ill and charged that the PWRC’s lawyer did not send an order of taking as directed by Masters.

Walesbilt Lake Wales gains victory in lawsuit, may regain ownership of historic Hotel

The appeal of an order of taking is “a real unusual circumstance,” DeHaven said.

The cooperative’s lawyer has filed additional declarations of taking since May. The most recent, filed in February, involves properties along Old Bartow Lake Wales Road, just south of Lake Ashton. None of the property owners contacted by The Ledger responded to voicemails.

As of this week, the PRWC had reached agreements on about 50 parcels, DeHaven said.

A pre-order of taking case management conference is scheduled for April 9 for the order involving Duke Energy property. Audrey Stasko, a spokesperson for Duke Energy, said by email, “Duke Energy does not comment on pending litigation.”

The pipeline will also cross land owned by Florida Southeast Connection, which operates a 126-mile underground natural gas pipeline installed in 2017. The company is a subsidiary of NextEra Energy, a publicly traded company that owns Florida Power & Light.

“Our top priority at Florida Southeast Connection is the continued safe operation of our pipeline, which is critical for the state’s energy needs,” spokesperson Chris Curtland said by email. “As such, we work collaboratively with public and private agencies if a safe crossing of our pipeline is needed, and we will continue discussions with Polk Regional Water Cooperative regarding its project.”

Small section already done

Though he isn’t directly involved in the legal actions, DeHaven tracks the progress of easement acquisition.

“It’s kind of a long-term process,” he said. “When you have to acquire so many easements, that is a challenge in itself. So, every time we go to the board each month, we kind of give the board an update on what's been acquired. We keep a running total, basically, of what's been acquired and the appraised cost versus the actual cost we paid. So, it's just an ongoing process.”

The cooperative is preparing to install the pipeline at a time when residential development is booming in Polk County. That sometimes provides an opportunity to collaborate with developers on having the pipes buried while the main construction work will occur.

A small section of the pipeline has already been buried during construction on Stuart Crossing, a development on Ernest F. Smith Boulevard in Bartow, DeHaven said. The PRWC also reached a deal to install pipe at a planned development in the Lake Hamilton area.

“We're constructing as they're constructing their development, so we don't have to tear up the front of their property twice,” DeHaven said.

For the most part, though, the PRWC will lay the pipe moving out from the main well site near Frostproof. Contractors will restore the land to its original condition as much as possible after the pipe has been buried, DeHaven said.

“If we rip it up, rip their driveway up, we’ve got to return that driveway back to the way it was. If we rip out some trees, a lot of times we compensate them for those trees. That's why we pay a little bit more than just the typical assessed value.”

Even as the acquisition of easements proceeds, the PRWC is considering bids on construction of the pipeline. The cooperative’s board, which is chaired by Polk County Commissioner George Lindsey, is scheduled to approve a contract at its next meeting on March 20.

DeHaven expects to have all the necessary easements for at least the first segment of the pipeline obtained by January, allowing major construction to begin early next year. The transmission project is broken into six construction packages.

The PRWC initially projected that water could begin flowing through the pipes by late 2026, though DeHaven said that 2027 now seems more likely.

Gary White can be reached at gary.white@theledger.com or 863-802-7518. Follow on Twitter @garywhite13.

This article originally appeared on The Ledger: Polk water partnership seeks access rights for 61-mile pipeline