Political beliefs hard-wired into brain, say neuroscientists

Neuroscientists at the University of Southern California led a study that found people are less likely to change their minds on political issues than on apolitical ones when presented with contradictory data.

The reason? Like religious beliefs, political opinions are intimately linked to how someone sees his or her own character and sense of community in a way that apolitical opinions simply are not, according to the researchers.

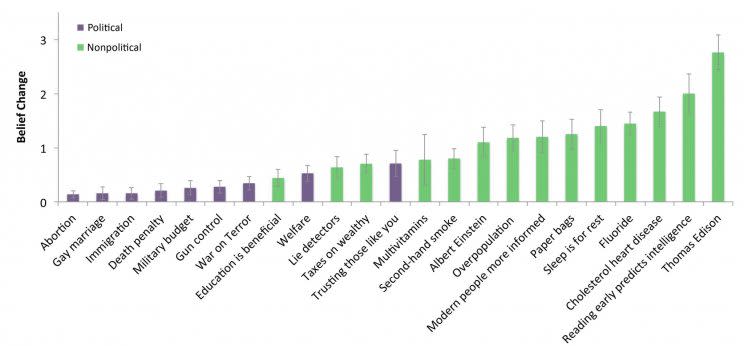

Their new study, published Friday in the journal Scientific Reports, found that people are more apt to reject evidence that challenges their opinions on subjects like immigration and gay marriage than evidence that challenges their opinions on topics like Thomas Edison or heart disease.

“If a belief becomes incorporated into our personal or social identity, then it’s much harder to change. We wanted to see what’s going on in the brain when people resist belief change,” lead author Jonas Kaplan said in an interview with Yahoo News. “You sort of become committed to this version of yourself that has a set of beliefs around certain topics.”

Are people willing to consider counterevidence to their opinions on early predictors of intelligence? Very likely! Are they willing to do the same for immigration policy? Many simply won’t budge.

Kaplan, a psychology professor at USC’s Brain and Creativity Institute, said part of the reason he and the study’s co-authors — BCI research scientist Sarah Gimbel and neuroscientist/philosopher Sam Harris — were interested in this topic is because it seems very important for humans to change their minds when they encounter new evidence.

“This is the principle that all science is based on. If we don’t change our views as we gather new evidence, what’s the point in gathering new evidence in the first place?” Kaplan asked.

The researchers invited 40 self-declared liberals and used functional MRI to study their brain activity when their thoughts were challenged. Kaplan said liberals were easier to access at the university but that his team is also interested in performing a similar study with conservatives.

Participants were presented with eight political and eight nonpolitical statements that they had claimed to believe with equal conviction. Then they were shown five counterpoints for each and asked to rate the strength of that belief on a scale from one to seven.

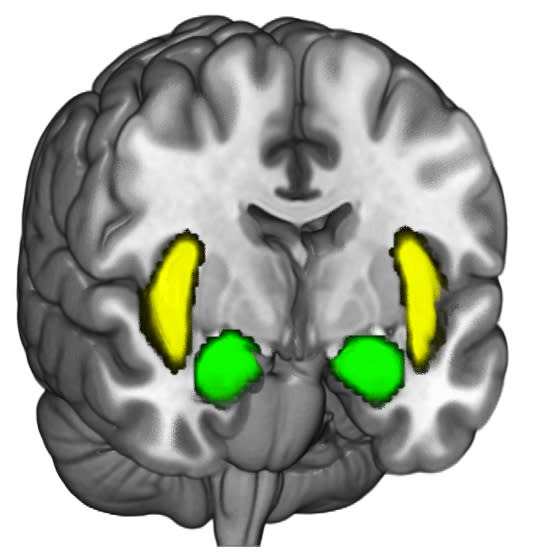

Neuroimaging showed that people most resistant to changing their beliefs had a spike in activity in the amygdala and the insular cortex, which are connected with emotions and decisions. More specifically, the amygdala perceives danger and anxiety whereas the insular cortex processes feelings. (Recent research shows that conservatives tend to have larger amygdalae than liberals.)

Humans are less likely to change their minds when feeling threatened, anxious or emotional, according to the scientists.

The study also showed heightened activity in a brain system called the default mode network when political beliefs were challenged. For Kaplan, who is also a co-director of USC’s Dornsife Cognitive Neuroimaging Center, it was one of the most interesting aspects of their findings.

“Understanding what this default mode network does is one of the big mysteries in neuroscience right now. So if we can make any contribution to how that works, that would be great,” he said. “What we’re seeing here is that when people think really deeply about things that matter to them, there is increased activity in that network.”

The researchers suggested that their findings might also apply to other issues, such as how a person responds to fake news stories.