How do police respond to a mental health crisis in the Boise area? It varies by agency

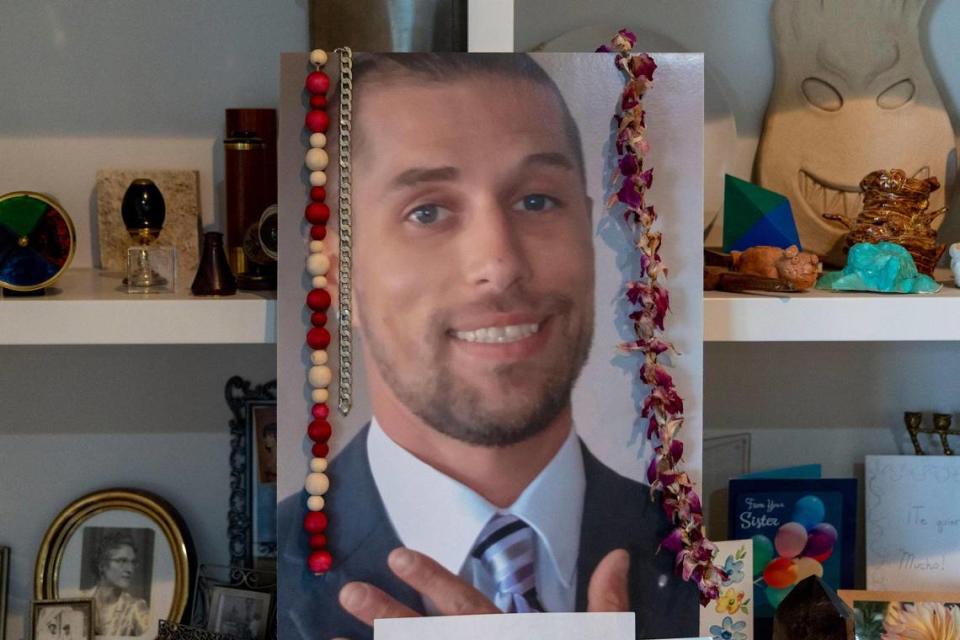

Skip Banach never thought his call into the Star Police Department for help would get his son killed.

The retired San Diego police officer told the Idaho Statesman that he’d warned Jeremy Banach how to act around law enforcement. But Jeremy had a substance abuse disorder.

In June 2022, Skip said he called Star police for help to remove his son, who had shown up at his parents’ home and refused to leave. Jeremy left the house with his father’s gun and police pursued him, according to the Ada County Sheriff’s Office.

Star Police Officer Jason Woodcook, who has since been cleared of any wrongdoing, fired five rounds at Jeremy’s back after Jeremy pointed a gun toward his own head and then walked away from officers, according to an investigative report published by the Ada County Sheriff’s Office and released body-camera footage.

The Sheriff’s Office said the gun was pointed toward an officer and a residential area behind Jeremy, but it’s unclear in the heavily edited footage. Jeremy was killed.

The 39-year-old was one of almost a half-dozen people suffering from a mental health crisis who were shot by an Ada County law enforcement officer in recent years. While it’s hard to count all police shooting fatalities that involved a mental health problem, an Idaho Statesman analysis of fatal and nonfatal police shootings in Ada County since 2021 found that at least seven people suffered from mental health issues or made suicidal statements.

Star police shot and killed two of them.

Ada County law enforcement agencies have had to adjust the ways they’ve responded to mental health calls, recognizing a need to do things differently. Two of the agencies, the Meridian Police Department and Ada County Sheriff’s Office, have even created mental health units that actively respond to calls with counselors as first responders, a change that the Meridian police chief said contributes to his agency’s low number of fatal shootings.

Jeremy Banach’s case wasn’t a crisis intervention call, according to the Sheriff’s Office. Patrick Orr, the agency’s spokesperson, pointed to an investigative report that had a summary of the initial dispatch call, which didn’t mention any mental health concerns. The city contracts its law enforcement duties with the Ada County Sheriff’s Office.

But Jeremy Banach’s mother, Gina Banach, said police knew Jeremy Banach was armed and disoriented, and that one of the responders knew of Jeremy’s drug history. She said police just let Jeremy Banach leave the house and only followed him once they learned the gun was stolen.

“Whether it was a crisis situation or not, there was no — as far as I’m concerned — no compassion, no empathy from any of the officers. They were just there to throw their weight around,” Gina Banach said. “They knew what they were going to do when they were standing at my front door long before they ever talked to Jeremy.”

In the nearly two years since Jeremy Banach was killed, his father has become one of the most vocal critics of police practices in the Treasure Valley. He’s appeared in front of the Star City Council, protested alongside Black Lives Matter in Boise over the fatal police shooting of 22-year-old Payton Wasson, and pressed for a citizen review board to investigate police shootings.

He’s also circulated a petition that asks for the Idaho attorney general’s office to conduct an “unbiased third-party review” of their son’s shooting. He said he’s lost faith in the system.

“I think the deputy sheriffs and the Star police are lacking in training,” Skip Banach said. “They apparently said they had crisis intervention training. They didn’t use that.”

Meridian police: No fatal shootings since 2018

There’s no doubt in Meridian Police Chief Tracy Basterrechea’s mind that his department’s mental health unit, known as its Crisis Intervention Team, is at least partly responsible for his agency’s nearly nonexistent number of police shootings in recent years.

The unit was created in June 2021. Since the beginning of that year, 20 people have been shot by law enforcement agencies throughout Ada County. Meridian officers were involved in only one of those shootings, despite being the state’s second-largest city.

The Meridian Police Department’s Crisis Intervention Team employs two specially trained officers and a licensed counselor. This setup allows the department to send a team member instead of a typical patrol officer to active mental health calls. Basterrechea said he’s hoping to add another counselor in the next year, which would be an annual increase of nearly $110,000 for the salaried position.

In comparison, the Boise Police Department — which has faced criticism over its handling of some mental health crises — has the highest number of police shootings since 2021: 14. The Ada County Sheriff’s Office was involved in four shootings in that span.

“These units can absolutely help you avoid those critical incidents,” Basterrechea said, speaking about his agency and a neighboring department’s mental health units. “But I will also say, man, sometimes luck just isn’t on your side.”

The Boise Police Department said its mental health unit focuses on reducing future calls by following up with people after a mental health crisis and handling repeat callers. The unit doesn’t typically respond to active calls, and in the case of suicidal subjects or someone who is armed, another unit could respond.

The Ada County Sheriff’s Office employs two specialized patrol deputies and two clinicians who can respond to mental health calls, Orr said. The unit also can be requested by patrol deputies to a particular scene and will typically handle any calls about someone on the county’s vulnerable population registry, a self-registered list that includes people who have dementia, Alzheimer’s or autism.

The Sheriff’s Office provided emailed answers to the Statesman and didn’t make anyone available for an in-person interview for this story.

Since Meridian’s unit isn’t part of patrol, its members aren’t constricted by other calls and can focus on one situation at a time, Ashley Horvath, one of the unit’s officers, told the Statesman during a ride-along. The department’s clinician can take the time to help calm someone who’s in crisis, Horvath added, and potentially provide a diagnosis or create a plan to help the person receive additional care.

Walking into the room with a clinician — someone who isn’t an officer and isn’t dressed in uniform like one — also helps ease possible tension, Horvath said.

“Sometimes it is hard for them to separate you’re a police officer who’s here to help me right now versus a police officer who’s here to arrest me,” Horvath told the Statesman.

How Boise police respond to crises

Skip Banach wasn’t the only parent whose call to police escalated into a fatal shooting.

In October 2021, when Melissa Walton called Boise police over concerns that her son, Zachary Snow, was suicidal and possibly planning to jump off a downtown building, she thought they’d help. She said she told her son to go talk to the police because “they’re going to help you.”

Officers shot and killed 26-year-old Snow after he pulled a hard black object from his waistband and “took a shooter’s stance,” according to the Boise Police Department. The object was a portable speaker, the agency said. Snow had a history of mental illness and was diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder at 18, according to prior Statesman reporting.

Walton has since filed two lawsuits against the city. The two officers who shot Snow were cleared by the Gem County Prosecutor’s Office, which reviewed materials from the Garden City Police Department after they investigated the shooting as a part of the county’s Critical Incident Task Force.

Snow was one of 23 people killed by the Boise Police Department since 2000. Last year, the department was involved in four fatal police shootings, making it the deadliest year in decades, the Statesman previously reported.

Most of Ada County’s officers and deputies have attended crisis intervention training, the standardized training in Idaho on mental health that entails a 40-hour class. Boise Police Chief Ron Winegar told the Statesman in an in-person interview that since so many officers have been trained in crisis intervention training, he doesn’t think it’s necessary to have a counselor in the moment of crisis. He said officers can handle mental health calls themselves.

“Generally speaking, a mental health clinician is best suited to help somebody not necessarily when they’re in the moment of crisis, but when they’ve worked with them after that (to) try to prevent them from reentering that crisis mode,” Winegar said.

But Ron Bruno, the CEO of Crisis Response Programs and Training, an organization that advocates for better crisis intervention training at police departments, said it was “never meant to be standardized training for everyone” and that departments still need specially trained officers.

Bruno, a former Salt Lake City officer, said specialized officers and clinicians should be responding to active calls alongside typical officers because they would be able to de-escalate situations more effectively, using negotiation tactics rather than weapons as a first response.

Given law enforcement agencies’ typical budget constraints, Bruno said he thinks departments should first prioritize training a fleet of crisis response officers who can be dispersed alongside patrol units, instead of funding one or two specialized units that are focused solely on mental health calls.

The Boise Police Department pays $541,000 annually for four salaries on its mental health unit, while the Ada County Sheriff’s Office Crisis Intervention Team costs around $500,000. Meridian police pays roughly $400,000 a year for its team of three employees.

When crisis intervention teams at these agencies are busy, any other mental health-related calls fall to patrol. Meridian police said their units also aren’t operational 24 hours a day, seven days a week, leaving a gap in service. The Sheriff’s Office units are available 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, Orr said.

Penelope Hansen, one of the Boise Police Department’s mental health coordinators, told the Statesman in an interview that its units couldn’t feasibly respond to every mental health call because of the sheer number of calls the department is receiving.

Last year, Boise police received over 4,000 mental health calls for service — including suicides — out of the department’s almost 135,000 calls for service. Meridian police had roughly 55,000 calls for service, with over 1,600 of them related to mental health.

One mental health unit at Boise police handles some crisis situations. The department’s 10-person Crisis Negotiation Team is called for a suicidal subject or other mental health crisis calls, particularly when patrol officers have been unsuccessful in negotiating with someone.

The unit also responds to hostage situations or people engaged in “terrorist activities,” the department said. If someone has a weapon, an extensive criminal history or an alleged crime, it’s more likely that the crisis team gets requested.

Boise Police Sgt. Tara Del Rio, who is a part of the crisis team, said the unit was called to help negotiate with a man with an extensive history of mental illness who had been driving around the city shooting a gun out of his window. She said there was a “high likelihood” that the incident could’ve ended in a police shooting but instead resulted in a “peaceful resolution.”

“That to me is a perfect example of where our team prevented anything further from happening,” Del Rio said.

Neither the department’s mental health unit nor the Crisis Negotiation Team responded to the call about Snow, according to an investigative report obtained by the Statesman. The department said it doesn’t typically call the team immediately.

But two of the responding officers had some crisis intervention training and were a part of the Crisis Negotiation Team. One of the officers said his training “never came into play” because he didn’t have enough time to use any of the de-escalation techniques he had learned.

A new approach to suicidal subjects in Meridian

Should officers even be responding to suicide calls? That’s a question the Meridian Police Department began asking years ago.

Basterrechea said he began pulling officers off of certain calls instead of having officers force themselves into people’s homes, a practice that he said immediately got pushback from police who were concerned the subject would become a danger to the community. But Basterrechea said people who are suicidal typically aren’t homicidal.

Basterrechea’s approach, a unique but increasingly common practice among law enforcement agencies nationally, is referred to as tactical disengagement. The Los Angeles Police Department implemented the method in 2019 following guidance from the U.S. Department of Justice, by having its Crisis Intervention Team, and not its SWAT team, respond to armed suicidal subjects, according to a 2022 article published in Police 1. If the person won’t comply, the unit likely won’t force their way into the home.

Amy Watson, a Wayne State University professor of social work, told the Statesman that the best response to suicidal calls is to “slow things down.” The officer should keep their distance, particularly if the individual is armed, so the officer can effectively communicate with the person in crisis and allow time to process any commands.

Watson said most people with serious mental health conditions are a bigger risk to themselves than others, but that sometimes people react negatively, especially when they are feeling cornered or threatened.

“Some of it has to do with who approaches them, how they’re approached, but certainly many of these situations could be handled very safely,” Watson said. “Sometimes adding police in the mix makes people feel more threatened.”

Star police involved in two shootings in two years

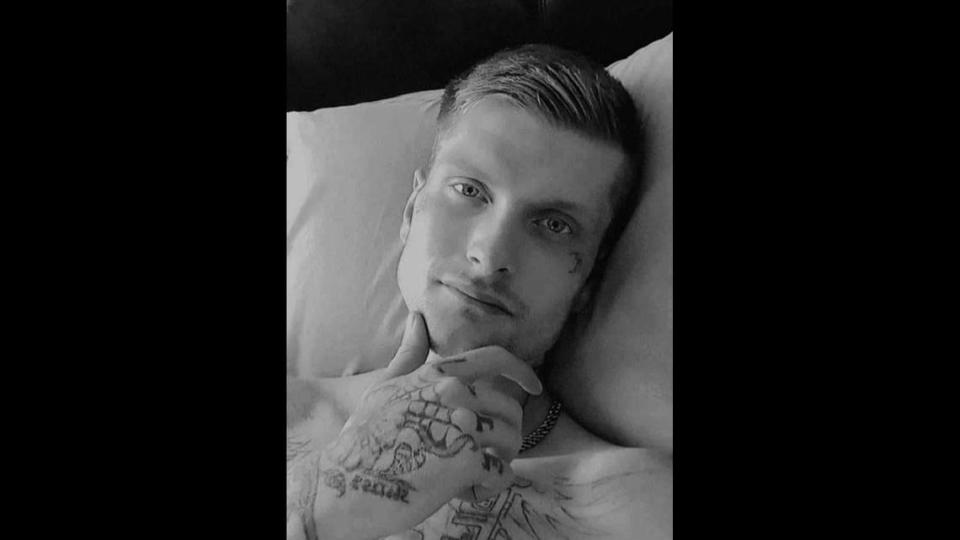

In September, Star police shot and killed another suicidal man.

The Ada County Sheriff’s Office said Star police officers found Chris Huffman, 41, in a field off the west side of Idaho 16, where he was waving a handgun. The agency said they asked Huffman “numerous times” to drop the gun until Huffman fired his gun at himself.

The Sheriff’s Office said police suspected Huffman was injured but still breathing, and as officers moved toward him, he moved his hands. He was ordered to stop and, after about 10 minutes, “Huffman grabbed the gun, sat up and began yelling at the officers and waving the gun around,” according to the Sheriff’s Office.

A Star officer, who has yet to be identified, fired at Huffman, who died from his injuries at a local hospital. The investigation into Huffman’s shooting is ongoing.

When Skip Banach moved to Star in 2014, about 7,300 people were living in the northwestern city flanked between Eagle and Middleton. Now there are almost 18,000 people.

“You cannot expect a community to grow like that — especially with low-income housing and stuff — and not have more problems,” Skip Banach said. “We’re going to have more shootings unless these guys are trained not to shoot except when the circumstances demand it.”

When asked whether the Star Police Department had any concerns about an increase in shootings being related to a boom in the town’s growth, Orr said the department doesn’t think there’s any connection, adding that both “circumstances were unique.”

Skip and Gina Banach say they’ll continue to push for police accountability. They maintain their fight for police shootings to be reviewed by a citizen review board, alongside neighboring law enforcement agencies and prosecutors. Skip Banach said he’d like the panel to be made up of former law enforcement officers who have never worked in Idaho, along with a mental health expert.

Since they’ve started pushing for change, the Banachs said they’ve lost friends who work in law enforcement.

”Most officers and deputies will not cross that thin blue line,” Skip Banach said. “To do so is to ostracize yourself from your department.”