Reform, defunding, abolition: Activists push plans to overhaul police departments

In the wake of George Floyd’s death and the worldwide protests against systemic police violence, different sets of activists have pushed for different strategies to make changes to law enforcement.

The breadth of the proposals is wide, from changes to training programs to reducing police department budgets to eliminating them entirely. Even though crime has been decreasing over the past quarter-century, all these proposals are set to face stiff opposition from law enforcement officials, police unions and Republican politicians primed to paint their opponents as soft on crime.

From reform to abolition, here are some of the strategies activists and elected officials are considering.

Reform

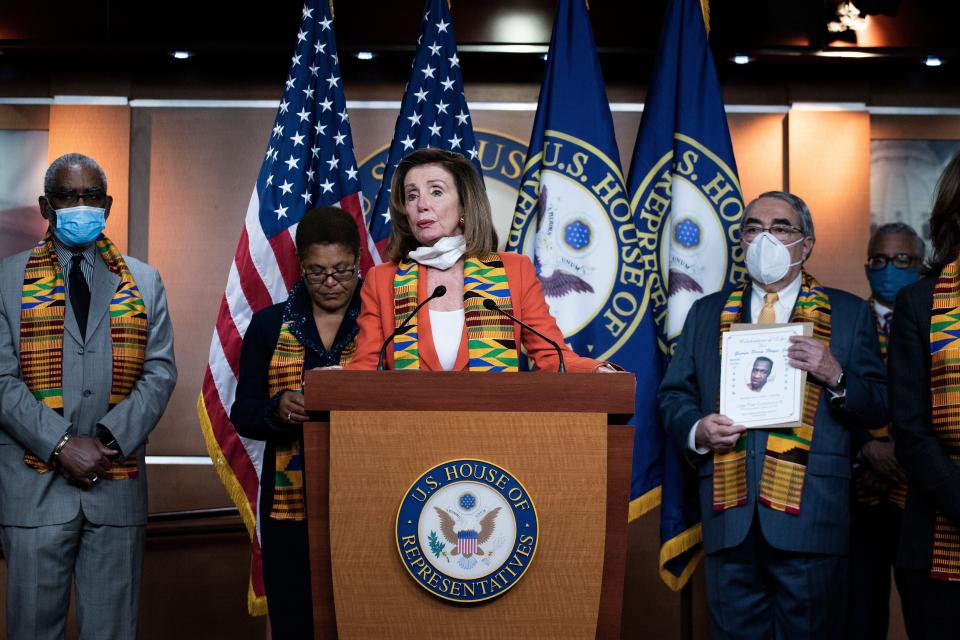

Congressional Democrats rolled out a long-shot reform plan on Monday. The Justice in Policing Act would include national use-of-force standards for police officers (including banning chokeholds), a countrywide registry of police misconduct, the creation of independent bodies to investigate such misconduct and a reversal of the militarization of police forces around the nation.

It also includes a partial rollback of qualified immunity, which shields law enforcement officials from being held personally liable for actions undertaken in the line of duty.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi appeared to try to get ahead of claims that the legislation wasn’t enough, saying it was “transformative” and “not incremental.”

“This is a first step,” Pelosi said. “There is more to come.”

The bill will face stiff resistance in the Republican-controlled Senate. White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany said Monday that some portions of the bill were “nonstarters.”

While federal officials have some control over policing, much of it falls to state and local officials. A set of proposals, called #8 Can’t Wait, from the anti-police-brutality group Campaign Zero, are targeted to individual departments and can be implemented immediately and at little or no cost.

The eight proposals include requiring officers to intervene and stop excessive force used by other officers, a ban on chokeholds, requiring a warning before shooting and a ban on shooting at moving vehicles.

While the organization says its plans are based on science, the data behind them has drawn criticism.

Jennifer Doleac, an economics professor at Texas A&M University and director of its Justice Tech Lab, wrote, “#8cantwait is not evidence-based. Their recs might be good steps, but please don’t pretend that the ‘data proves’ they work. We do not know if they work yet. Brilliant marketing strategy though, I’ll give them that.”

Defund

Other activists will say that reforms have been attempted for decades and simply aren’t enough, as officers still turn off body cameras or ignore bans on certain tactics like chokeholds. Their approach to rein in police power is to reduce — or, in some cases, completely eliminate — their budgets, which dwarf all other spending in many cities.

For example, a 2017 analysis from Forbes found that Chicago, Houston, Minneapolis and Orlando all spent more than 30 percent of their city’s general fund on police. There are also settlements for police-misconduct lawsuits, which cost major cities tens of millions every year.

As pointed out in the Atlantic, the U.S. spends 18.7 percent of its annual output on social programs, compared with 31.2 percent by France and 25.1 percent by Germany. Police also benefit from U.S. massive spending on the armed forces — the most of any nation on earth — as departments are the beneficiaries of military surplus that results in small towns sometimes owning armored troop transports.

“The demand of defunding law enforcement becomes a central demand in how we actually get real accountability and justice,” Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors told Boston’s WBUR, “because it means we are reducing the ability of law enforcement to have resources that harm our communities.”

“It’s not just about taking away money from the police, it’s about reinvesting those dollars into black communities,” continued Cullors. “Communities that have been deeply divested from, communities that ... have never felt the impact of having true resources. And so we have to reconsider what we’re resourcing. I’ve been saying we have an economy of punishment over an economy of care.”

Proponents of defunding the police want that money rerouted to social programs and education budgets that have been slashed. Activists argue that such budget cuts have left police dealing with problems that would be better left to social workers, drug counselors, mental health experts, and funding for schools and housing. For example, officials in Portland, Ore., announced they would be canceling a plan to have officers in schools and will reroute the $1 million that was going to pay for it to a “community-driven” program.

It is an attempt to solve the problem, as former Dallas Police Chief Donald Brown said in 2016, of the police being asked to do too much, most of which they are not prepared to handle.

“We’re asking cops to do too much in this country,” Brown, who is now the Chicago police superintendent, said. “We are. Every societal failure, we put it off on the cops to solve. Not enough mental health funding, let the cops handle it. … Here in Dallas we got a loose dog problem; let’s have the cops chase loose dogs. Schools fail, let’s give it to the cops. … That’s too much to ask. Policing was never meant to solve all those problems.”

The campaign of presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden said Monday that he didn’t support defunding police but wanted instead to increase budgets for other programs.

“As his criminal justice proposal made clear months ago, Vice President Biden does not believe that police should be defunded,” campaign spokesman Andrew Bates told reporters, adding, “Biden supports the urgent need for reform — including funding for public schools, summer programs, and mental health and substance abuse treatment separate from funding for policing — so that officers can focus on the job of policing.”

Democratic mayors from the country’s largest cities have claimed they are going to make at least slight alterations to police budgets in the wake of the protests. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio said the city would move funding from the NYPD to youth initiatives and social services. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said he would cut as much as $150 million from a planned increase in the LAPD budget.

However, an investigation from the Marshall Project found that simply defunding doesn’t necessarily improve results without a full reimagining.

“I am a proponent of good government and efficiency and not overspending on something that you shouldn’t,” said James McCabe, a former NYPD commander who now consults with a number of departments. “But it might be a little bit of a knee-jerk reaction right now to just unilaterally defund the police because you don’t like something that happened.”

The L.A. police union, meanwhile, has warned that budget cuts would harm the department’s ability to deliver essential services.

“Cutting the LAPD budget means longer responses to 911 emergency calls, officers calling for backup won’t get it, and rape, murder and assault investigations won’t occur or will take forever to initiate, let alone complete," said the board of the Los Angeles Police Protective League in a statement last week, adding that the budget cuts would be “the quickest way to make our neighborhoods more dangerous.”

Prior to the Biden campaign’s statement, President Trump had already attacked the former vice president for wanting to cut police budgets, tweeting more than a half-dozen times that his likely general election opponent and “radical left democrats” wanted to defund the police.

McEnany said Monday that Trump was “appalled” at the idea of defunding police, but his attempts to paint himself as a “law and order” candidate have not stopped his slippage in the polls.

Abolish

The most extreme option being proposed is the total abolition of police forces and a complete reimagining of how public safety works. Those calling for abolition (or total defunding) point to decades of attempted reforms having failed and the need for drastic change, including an end to mass incarceration.

There is a lot of overlap between arguments for defunding and abolition. Proponents of both strategies say police wouldn’t have to deal with the homeless if more money were spent on public housing, nor would they have to deal with nonviolent drug offenses if more substances were decriminalized.

The argument for the abolition of police cites their disproportionate targeting of people and communities of color. A 2015 Department of Justice report into Ferguson, Mo., found police abused and fined lower-income, predominantly black residents to increase revenue for the department. Proponents of abolition also cite pre-Civil War runaway slave patrols that served as precursors to some police forces, particularly in the South, as a reason the relationship between police and communities of color is beyond repair.

“The reality is a lot of people just don’t call the police as it is, because they feel like it’s just going to make their lives worse,” said Alex Vitale, a Brooklyn College sociology professor and author of “The End of Policing.”

MPD150 is an organization in Minneapolis calling for police abolition that has seen its stature grow in the aftermath of Floyd’s death.

“In this long transition process, we may need a small, specialized class of public servants whose job it is to respond to violent crimes,” wrote the group. “But part of what we’re talking about here is what role police play in our society. Right now, cops don’t just respond to violent crimes; they make needless traffic stops, arrest petty drug users, harass Black and Brown people, and engage in a wide range of ‘broken windows policing’ behaviors that only serve to keep more people under the thumb of the criminal justice system.”

On Sunday, a majority of the Minneapolis City Council said they would vote to disband the city’s police force, which has a long history of misconduct. The day before, Mayor Jacob Frey was heckled by a large crowd after refusing to commit to the total disbanding of the force.

Council members said the timetable would be long and that they were unsure of exactly what a new law enforcement system would look like.

“In Minneapolis and in cities across the U.S., it is clear that our system of policing is not keeping our communities safe,” said City Council President Lisa Bender. “Our efforts at incremental reform have failed, period. Our commitment is to do what’s necessary to keep every single member of our community safe and to tell the truth: that the Minneapolis police are not doing that. Our commitment is to end policing as we know it and to re-create systems of public safety that actually keep us safe.”

The total elimination of police is likely to be a politically difficult position, as police have polled well for decades. Even in the wake of the Floyd protests, 71 percent of respondents to a Monmouth poll said they were either very or somewhat satisfied with the job of their local police department, roughly in line with the same answer five years earlier.

One potential scenario for the future of Minneapolis police, if the city goes through with abolition, is Camden, N.J. In 2013, the Camden Police Department was disbanded and restarted as the Camden County Police Department, with more officers doing “community policing,” which focuses on officers building bonds with residents in an attempt to establish trust and a sense of cooperation.

The city has seen a reduction in violent crime and excessive force complaints but a rise in low-level arrests and summonses, which can be crippling to low-income residents. The police department also became significantly less diverse after disbanding. Many of those calling for total defunding or abolition would not count Camden as an example, but it represents a possibility of what total dismantling and reimagining could look like.

“People say, ‘What about sexual violence, and what about domestic violence?’” said Andrea Ritchie, a researcher for Interrupting Criminalization at Barnard College, in an interview with NBC News.

“The people who are advocating [to] defund police and abolish police are, for the most part, black women, girls, trans and gender-nonconforming people. Many of us are survivors of all those forms of violence. We are not proposing to abandon our communities to violence. We are naming policing as a form of violence that we all experience.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: