How Planes Became Firefighters' Best Friend—And Then Drones Became Their Worst Enemy

They almost had it.

"The firefighters thought they had it trapped in this bowl," Utah Governor Gary Herbert says, describing the valiant, desperate attempts to contain a wildfire's consuming hunger during the excruciating heat of the summer. "They were bringing in some fixed-wing aircrafts, tarps, and suppressant….to keep it contained."

Then the real crisis arrived-an aerial terror armed with four-humming motors.

"On the ground, they're saying vacate the airspace," Herbert told Popular Mechanics. "We had [the fire] trapped-and it got away from us because of a drone."

This fire, now known as the Saddle Fire, raged across the state throughout summer 2016. Before it burned out it would see multiple instances of drone interference with firefighting efforts. On June 22, Herbert angrily tweeted about the incident and held a press conference denouncing the drone users. A few weeks later, a fifth drone incident brought aerial firefighting operations to a halt. Voluntary evacuations soon became mandatory for 185 structures and homes. Soon, what would have amounted to only a couple million in fire suppression costs quickly ballooned to $14 million.

Two days later, at a special session of the legislature originally meant to deal with potential sales tax breaks for data centers, drones instantly took center stage. The chamber passed a law that allows for jamming drones, shooting them down, and issuing serious fines and jail time.

Firefighters praised the quick legal action. But it wasn't enough. Just two weeks later, another drone stopped aerial firefighting efforts, causing more evacuations.

Decades ago, aviation changed firefighting forever, allowing crews to see a fire's reach and attack it from above. Now, as cheap consumer drones proliferate, aviation is quickly becoming a firefighter's worst enemy.

The Tech That Changed Firefighting Forever

The earliest known attempt at aerial firefighting happened in 1930, when the U.S. Forest Service used a Ford Tri-Motor airplane to drop a wooden beer keg filled with water over a fire. But in the years before World War II there really wasn't much firefighters could do to fight fires in rugged, woodland areas.

After the war, however, the U.S. had a huge surplus of military planes. Specifically, Boeing-Stearman Model 75s, biplanes built in the 30s and 40s.

People at the time immediately thought to use them as crop dusters, but Joe Ely, who in 1955 was working for the U.S. Forest Service in California, thought the planes could be rigged up with water for suppressing fires. He soon found an ally in Floyd Nolta, an experimental agricultural pilot first profiled by Popular Mechanics in 1940 and called "one of the West's leading dusters."

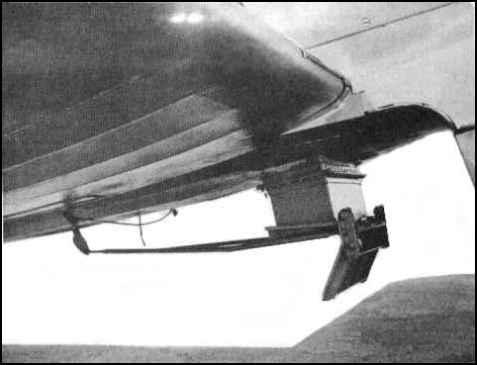

To modify these World War II fighters, Nolta "cut a hole in the bottom of a Stearman biplane," Ely recalled in 1981, and "added a gate with hinges and a snag and pull-rope, and filled the thing with water." When they discovered that water would just evaporate during its free-fall journey, Ely and Nolta created a concoction of water and sodium calcium borate that wouldn't evaporate so quickly. The duo quickly replaced the slurry with an even better mixture.

Aviation as an Enemy

In the decades since then, aerial firefighting has grown in predictable ways, Crop dusters have transformed into air tankers, slapdash slurries have become researched scientific recipes.

Then the drones came.

The commercial drone revolution, which has turned a onetime military gadget into a soon-to-be $5 billion industry accessible to millions of people, has given us a lot. The freedom to fly and shoot amazing videos from previously inaccessible heights, for one. But along with amazing YouTube fodder came drones trespassing where quadcopters should fear to tread, such as around airports, football stadia, and the flames of the fire-ravaged West.

While legal restrictions on drones don't allow drones higher than 400 feet in American airspace, operators who flout the rules have flown as high as 11,000 feet. With aerial firefighting generally taking place at about 1,500 feet, that means drones are flying in the same airspace as fire-fighting tankers.

Manned firefighting aircraft can be broken into two categories: big and small. There are the giant tankers, actually known as Very Large Air Tankers (VLATs), which are converted DC-10s. But there are also smaller helicopters, Vietnam War-era AH-1 Cobras, that direct tankers with on-sight visuals and GPS. In addition to these copters, other single-engine tankers require extreme precision.

Trained pilots have crashed and died fighting Utah fires because they did not properly calibrate for wind conditions. Drones only add another layer of unpredictability."With vulnerable rotor systems and helicopters, it's uncomfortable when you know there might be something flying around you that you can't see and you don't know when or where it's coming from." So said Jason Curry, the public information officer at the Utah Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands, to Utah Public Radio,

"It's kind of a slap in the face for firefighters to have to face that reality," Curry added. "People are willing to put their lives at risk for the sake of a snapshot."

Drones Go to Court

In 2015, a fire approached the home of Utah State Rep. Kraig Powell in Heber City, which borders a national park. "People were concerned about that fire reaching homes," he tells Popular Mechanics, "and then one day the firefighting crews announced that they had to ground the planes because of a drone that was flying in the area." Powell did some digging and found no law on the books beyond general "don't interfere with fire" laws. So he wrote his own, creating a specific $2,000 penalty for flying a drone over a fire.

Powell considered the whole thing pretty non-controversial. But Powell says that "both the drone industry and...Google had lobbyists at the Utah state capitol and they inserted some language that really watered down the bill."

The biggest concern was who got to control the no-fly zones that would establish where drones were banned: Powell wanted to give local bodies that ability, but larger companies, especially those currently making a bet on drone-based commerce, said that any regulation on a local level will come back to haunt them in the coming years. Google declined to comment on Powell's statement.

But drones don't have to be an enemy. Lockheed Martin's Indago quadrotor have been used in Western Australia, saving hundreds of homes. The company also tested its K-MAX helicopters in Idaho for fighting fires. The tests apparently went so well that Lockheed has put out a video of what looks like a full-service drone-based firefighting system: the Indago discovered the fire, the K-MAX put it out, and a UAV conducted a search-and-rescue mission.

These new laws are only opening salvos in what promises to be an ongoing aerial war. Other states are ramping up their legislation, and companies like DJI are embracing geofencing that would prevents flying into places like airports and ongoing forest fires. The U.S. Department of Interior has also been building maps to help implement geofencing. All great ideas, but if the recent hacking and Internet of Things scandals have taught us anything, it's that there is no surefire way to keep modern technology from doing precisely the things they shouldn't be doing.

With global warming only exasperating forest fires worldwide, bringing them to places where they haven't been seen before, it's more important than ever that firefighters have every possible advantage. But more likely that not, the drones will keep coming for an aerial glimpse of one of nature's most destructive forces. If we can't eliminate, we must adapt.

You Might Also Like