US mobster Skinny Joey gets two years in prison – and agrees with Trump on 'flippers'

Purported crime kingpin Joseph Merlino, 56, sentenced to two years in prison for operating an illegal gambling business

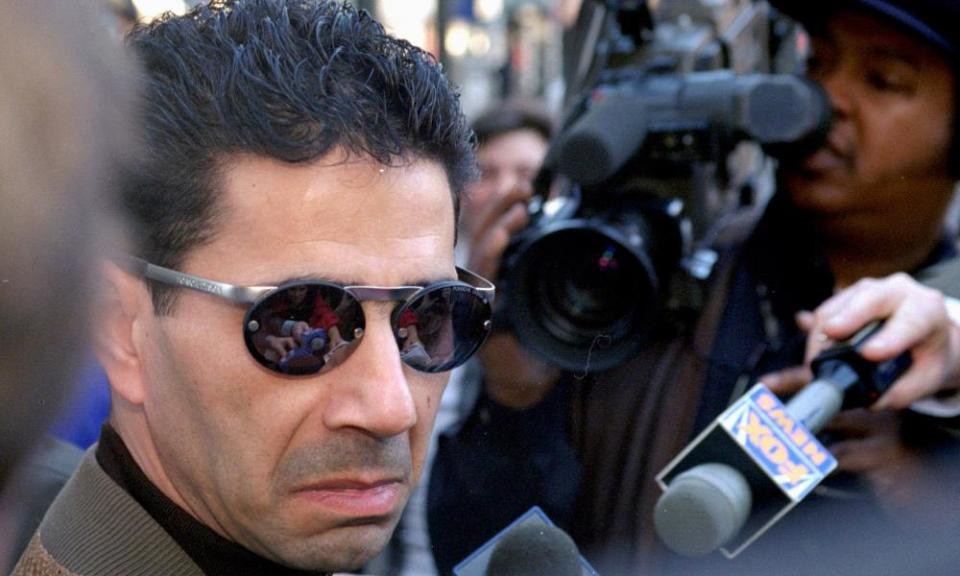

Joseph “Skinny Joey” Merlino was living what many a middle-aged gangster would consider a coveted life.

After serving much of a 14-year sentence related to racketeering, the purported crime boss traded Philly’s bitter winters for a home in the balmy, South Florida suburb of Boca Raton.

He settled into a $400,000 townhouse in a nondescript cul-de-sac in a “cookie-cutter” neighborhood, according to the Miami Herald. Merlino, who reportedly survived 25 attempted hits in his heyday, told the Herald that his new line of work was a carpet-installation outfit.

But trouble overran Merlino’s new life.

He landed back in jail for four months after hanging out with an old mob buddy at a cigar bar. And in August 2016, he was one of 46 accused mobsters implicated in a massive racketeering scheme that spanned the eastern seaboard, prosecutors said.

The Manhattan US attorney’s office claimed the Philly, Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese and Bonanno crime families were all working together in this single scheme.

After it was revealed that two FBI agents on the case might have mishandled a key witness, many of these men were offered plea deals on lesser charges, and decided to plead guilty.

President Trump was right. They need to outlaw the flippers

'Skinny Joey' Merlino

Merlino, long known for courting the media, bucked the trend and his case went to trial in January. The proceeding ended in a mistrial because of a deadlocked jury. Instead of retrying the case, prosecutors and Merlino’s lawyers brokered a deal.

Merlino, now 56, wound up pleading to a single gambling-related count in April.

On Wednesday, he was sentenced to two years in federal prison.

Asked if he wanted to comment outside the courtroom, Merlino said no, and focused his attention on a water fountain. But when he left the courthouse, Merlino offered thoughts on mob informants who had cooperated with authorities to help put him back in jail.

“President Trump was right. They need to outlaw the flippers,” he remarked.

Merlino’s sentencing, however, doesn’t just mark an apparent conclusion to a high-profile mob case. His impending prison time may indeed speak to the longtime decline of the cosa nostra.

Elements of Sopranos-style organized crime do continue to exist – and, given the bloodshed and death associated with these elements – remain bizarrely romanticized.

But gone indeed are the days of John Gotti’s gaudiness, such as the fancy Brioni suits that landed him the moniker “The Dapper Don,” and the glitz captured in films such as Casino.

(Merlino, once known as the “John Gotti of Passyunk Avenue”, sported a knit hoodie on the first day of his trial.)

The legalization of many stalwart mob industries – such as gambling – has also left many made men unable to make a decent living.

“For what’s left of what they do, this would significantly hurt their bottom line, if not completely destroy it,” John Meringolo, one of the lawyers representing Merlino, previously told the New York Post. “If there’s no gambling, there’s no core business.”

Kenneth McCallion, a former federal prosecutor who several decades ago investigated possible ties between the mafia and Donald Trump, told the Guardian that by the early 1990s, mobsters had hit an identity crisis.

“We would pick up on wiretaps, or from sources, that the culture of organized crime was so eroded, some of the members would have to watch TV or movies to see how wiseguys walked and talked,” McCallion said. “So, that was kind of the beginning of the end.”

Families that may have got into the mob, meanwhile, became increasingly disinterested in the life – requiring bosses to import prospects to “beef up their ranks,” he said.

Merlino’s imprisonment may deal a severe blow to what remains of Philadelphia’s mob.

Historically, when leaders wound up behind bars, “what it triggered would be a power struggle within the organization,” McCallion told the Guardian.

Judge Richard Sullivan, who handed down the maximum sentence, said he didn’t think Merlino was the “boss” of Philadelphia’s family. But Sullivan didn’t buy arguments by Merlino’s lawyers that he had been a “degenerate gambler” since age 13 and slipped back into crime for money.

“You were a player,” Sullivan said.

Regardless of Merlino’s status in the Philadelphia mob’s hierarchy, he still appears to hold considerable sway over his supporters, who filled more than half the courtroom.

“It’s all bullshit,” one man in the gallery loudly groused during sentencing. “Rat bastard.”

“You want to talk over me?” an incensed Sullivan retorted. “You want to be quiet?”

“Yeah, sure,” the man said dryly.