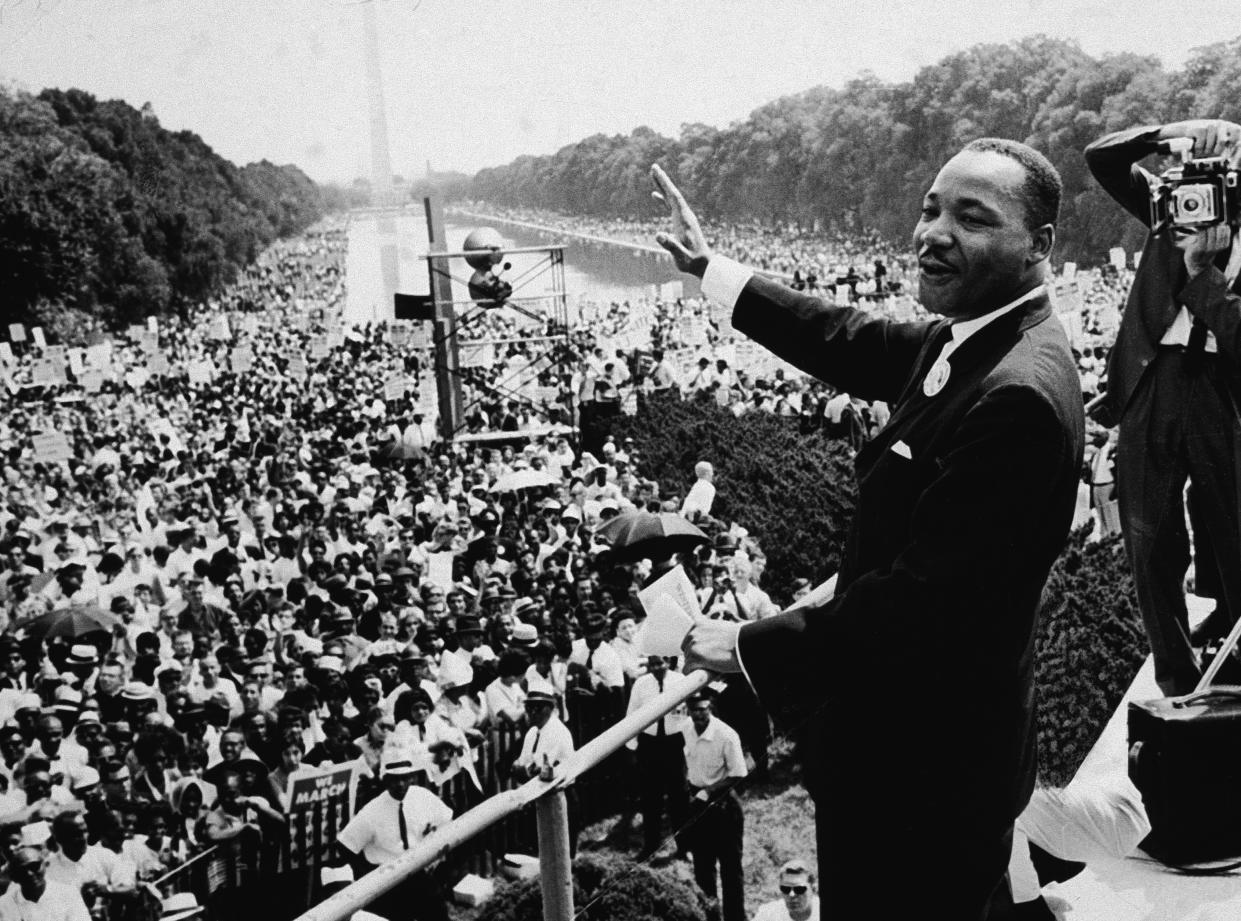

The persistence of grace: Martin Luther King Jr., Jan. 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968

Fifty years ago, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., who preached nonviolent resistance to oppression and war, was shot to death in Memphis. He was 39 years old. He left behind a wife and four children and a nation still riven by the divisions he had devoted his life to healing. Yahoo News takes a look back at his life and his legacy in this special report. Jonathan Darman assesses King as a man not without flaws, but with a passion for justice and a conviction that grace can still be found here among us sinners on earth. Senior Editor Jerry Adler looks back on the fateful last year of King’s life, beginning with his electrifying, and controversial, Riverside Church address against the war in Vietnam. National Correspondent Holly Bailey goes back to Selma, Ala., whose poverty moved King to increasingly turn his focus to economic justice, and finds not much has changed in the years since. Reporter Michael Walsh looks at how King almost died in an attack a decade earlier, and how the knowledge of his mortality shaped his ministry and message. Gabriel Noble’s video explains how a new generation of activists draws inspiration from King’s message.

He was a man, not a god.

As a small child, Martin Luther King Jr. was serious and spoke in sentences that startled grownup ears, but he struggled with spelling and suffered through violin lessons, studied too little and ate too much. When his father would beat him, he held back his tears.

In his teenage years, he became a fastidious dresser, nicknamed “Tweedy” by his friends. As a young man, he fell in in love with a white woman he knew he could never marry. Interracial marriage was something that neither his parents nor his future plans would abide. He experienced the exquisite agony of the young, a doomed romance.

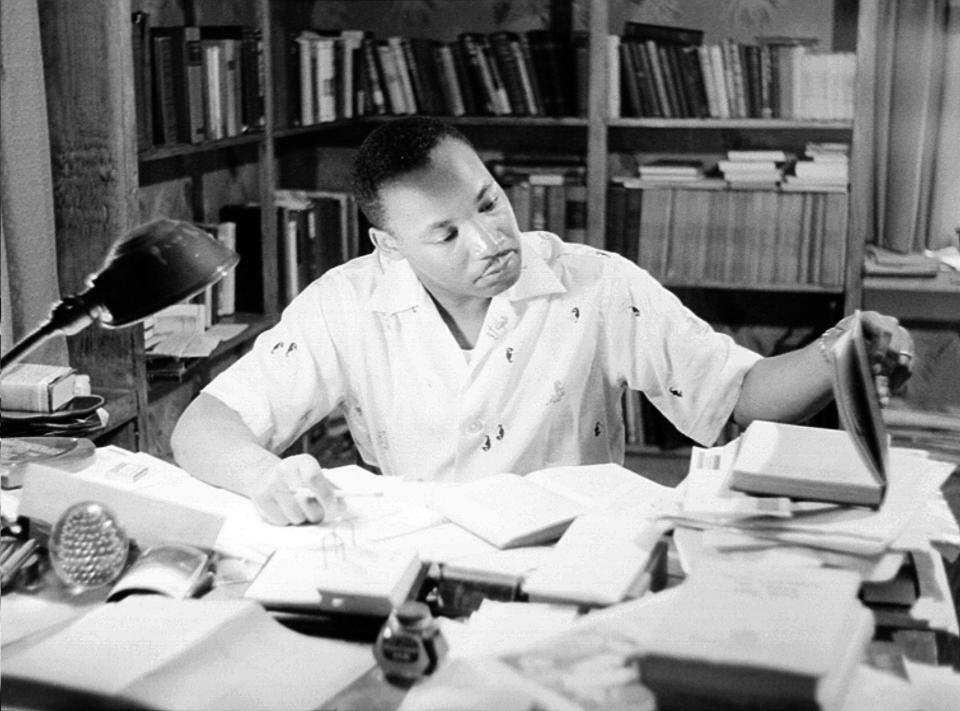

He was, of course, extraordinary. He read everything he could get his hands on, devouring the ancient classics and the Bible, Shakespeare and Freud. Reinhold Niebuhr challenged his faith, Thoreau opened his eyes, Gandhi shaped his life’s work. His gifts were readily apparent. By the time he arrived at Crozer, the integrated Pennsylvania seminary he attended after Morehouse College, he had become an electrifying speaker. “A generation later,” writes Taylor Branch, author of the majestic trilogy “America in the King Years,” “white students who remembered very little else about King would remember the text, theme, and impact of specific King practice sermons.”

Such enthralling preaching appeared effortless, but it was in fact the product of careful preparation, repetition and work. As the young pastor of Montgomery, Ala.’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, he would rise before 6 o’clock most mornings to draft and memorize next Sunday’s sermon and perfect his delivery in front of his bathroom mirror.

His failings were ordinary and human: He was perpetually late, he struggled endlessly to keep his weight down. He was capable of vanity, jealousy and deception. He was chronically unfaithful to his wife. To the world, he showed unimaginable, unbreakable courage through years of death threats, arrests and persecution. In private, he nursed doubts. At the outset of the Montgomery bus boycott, he had been “possessed by fear” and “obsessed by a feeling of inadequacy,” he would later recall. In “At Canaan’s Edge,” his final volume on King’s life, Branch recounts an evening in the fall of 1967 when King drank too much whiskey and despaired over divisions in his movement. “I don’t want to do this any more,” he cried, “I want to go back to my little church.”

“You don’t need to go out this morning saying this Martin Luther King is a saint,” King preached to his congregation a few months later. “Oh, no. I want you to know that I am a sinner like all of God’s children.”

Yet 50 years after his death, King looms high above us, out of our reach. When we learn the history of the 1960s, his peers are men in full. John F. Kennedy has his special grace but also his grotesque womanizing and his selfishness. Lyndon Johnson’s transcendent legislative genius in the causes of civil rights and social justice sits beside his petty cruelty and the demons that helped bring him down. Even Richard Nixon is allowed not just his cunning and wickedness but, also, moments of brilliance and kindness too. To the extent we examine King’s own womanizing, it is usually when discussing his unjust persecution at the hands of J. Edgar Hoover. He is the only one of them with a memorial on the National Mall and he has become, like George Washington, an idol cast in stone.

This was, perhaps, the inevitable fate for any black hero in America’s story. As a young man in seminary, King chastised a classmate for keeping beer in his dorm room, reminding him of “the burden of the Negro race.” America, he knew, might allow for greatness in a black man, but only so much humanity and precious little vice. The generations of black leaders who’ve followed King have learned this lesson too.

What’s more, putting King on Mount Olympus has let us reassure ourselves that his struggles are, like Washington’s, in the distant past. For decades now, schoolchildren have recited his “I Have a Dream” speech and understood it as part of a happy story: He had a dream of racial equality, and in time that dream came true.

But now, the darkness he fought is near again and we cannot pretend it is the past. Not when cellphone videos show police murdering innocent young black men, not when far-right extremists with torches march through an American city at night. Here and there in our troubled time, we see glimmers of King’s example: in the faces at Ferguson, in the crowds at the Women’s March. We see it in the courageous example of the student activists of Parkland, Fla. Like him, they know that acts of violent injustice deserve not just condemnation but a demand for change.

Still, King’s core belief, his faith in the power of a transformative and limitless love, seems depressingly alien to our age. Hate is in much more ready supply. We can find it at any time, not just from the usual providers — the violent extremists, the cable news demagogues, the president of the United States — but in our own hearts. It comes to us, familiar and delicious, as we scroll through our newsfeeds each morning, waiting for the inevitable new outrage, proof of how craven, corrupt or ignorant half the world has become. We like and we retweet and we get no sustenance in our souls.

King’s life story reminds us there is an alternative. To free ourselves from injustice, he taught, we must first free ourselves from hate. He urged his followers to love their enemy, to see his humanity and, in time, to change their enemy’s heart. “Threaten our children,” he preached, “bomb our churches and our homes and, as difficult as it is, we will still love you. … We will not only win freedom for ourselves, we will so appeal to your heart and to your conscience that we will win you in the process. It will be a double victory.”

If, half a century after his death, the victory has not arrived, it is not yet beyond our reach. Today, we remember King’s uncommon brilliance as an orator, his resolve at Selma, his courage in Birmingham. But we must remember too his humanity, for it is proof that grace exists in our broken world. In his lifetime, King beseeched his country to seek out a love which surpasses all understanding. Fifty years later, we can still find it, not in the heavens, but here on Earth.

_____

Jonathan Darman is the author of Landslide: LBJ and Ronald Reagan at the Dawn of a New America. (Random House, 2014)

_____

Read more of our coverage of: