Is Peoria safe? Can the city tackle education? 5 takeaways in the contentious Peoria mayoral campaign

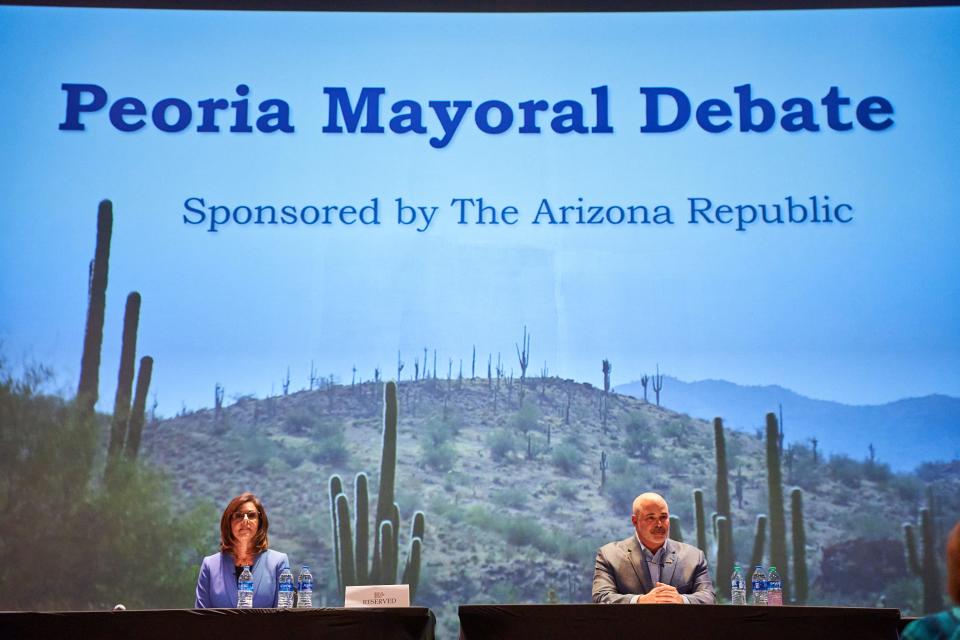

Bridget Binsbacher criticizes her opponent for building fear over crime in Peoria, and Jason Beck bashes Binsbacher for prioritizing parks over police.

The pair are engaged in one of the most contentious, expensive and partisan mayoral races in the city's recent history.

The Arizona Republic dug into both issues, as well as how each candidate would attract jobs to the city, something both say they'll do.

Then there are Beck's education plans, an unusual component in a municipal race but a cornerstone of his campaign, and Binsbacher's push on transportation issues.

Education plans

The Peoria Unified School District has its own elected governing body and taxing authority, but Beck has campaigned on the idea of bringing to new high schools to the district — one near the Vistancia community in north Peoria and one that is STEM-related — without bonds or new taxes.

“Part of the issue is that the current (city) administration does not believe that they should actually have anything to do with education whatsoever,” Beck said.

Binsbacher has fired back that his plan isn't legal. "The city is not the legal taxing authority for education," she said.

Public schools are funded by school districts, which receive their funding from the state, county and property taxes and often federal grants.

How it works: Arizona school funding

Beck, however, said he has a strategy to fund education indirectly. One idea is for the city to purchase land from the Arizona State Land Department, which shares revenue from the sale of state trust land with eight beneficiaries, including universities and K-12 education.

Beck said the city needs to figure out how to funnel the proceeds from the sale of the land to PUSD. “It’s all a negotiation,” Beck said. “I also think that you actually work with your state legislators as well. Right now, we don't do that.”

Where revenue from state land sales is distributed, however, is predetermined by the state constitution, State Land Department spokesperson William Fathauer told The Republic. Thus, there's no room to negotiate funneling funds from the sale of state land directly to select school districts.

Instead, when the land department auctions off a parcel of land, the state Treasurer’s Office invests the revenue. Gains on the investments intended for education are then sent to the Arizona Department of Education, said Mark Swenson, deputy treasurer for the state Treasurer’s Office.

From there, the money is distributed to schools based on funding formulas set by the state Legislature.

Beck could hypothetically advocate during the Legislative budgeting process, although "the funding formula is complex and based on various factors each year," said Jimmy Arwood, a state education department spokesperson. "Generally, funding is based on enrollment numbers."

Another localized way to advocate for school funding would be at the district level through voter-approved bonds, at the ballot box for proposition-based funding, or the district itself applying for grants, he said.

How safe is Peoria?

Beck, who is endorsed by the city's police association, says the city hasn't hired enough police officers and needs to fund public safety before parks. He says a lack of staffing and funding have led to rising crime and response times.

Binsbacher, while on City Council in January, approved 15 new full-time police officers, but Beck questioned why it wasn't done sooner, suggesting it was for political advantage.

Binsbacher said Beck was giving himself “way too much credit” and that “those decisions don’t just happen on a whim or as a response to a political opponent.”

The city funded the new positions because they could afford to, she said, adding that the city escaped the pandemic in a much better financial position than expected.

“I don’t think we’ve refused them anything that they’ve ever asked for,” Binsbacher said of the police and fire departments.

Binsbacher said she wasn’t sure where critics were receiving their information but that it was “irresponsible to instill false fear in people to create issues as if he's the only one that can come in and solve them. I'm looking to our police chief and our department's leadership as to what our needs are.”

Election guide: November 2022

City races | School boards | State | Governor

| Ballot measures | Federal races | How to vote

Here's what the city budget, staffing and response time data shows:

Police and fire are the top funded departments in Peoria. The City plans to spend 37% of its general fund on police and fire in fiscal year 2023, which runs July through June. Of $278 million in the general fund, $59.5 million will go to police and $44 million will go to fire.

Peoria police averaged about 8 sworn officer vacancies per month between 2017 and 2021, according to public records provided to The Republic. Sworn officer vacancies have reduced over time, from an average of 17 per month in 2017 to 6 per month in 2021. At the same time, the department has added personnel.

In 2021, in life-threatening situations, it took Peoria police an average of 7 minutes, 16 seconds to arrive after an emergency call was made. The response time was the same in 2016, according to city data.

In 2021, in non life-threatening situations, it took Peoria police an average of 13 minutes, 11 seconds to arrive after a call came in. That was an improvement over 2016, when the response time averaged 16 minutes, 7 seconds, according to city data.

Important context: Most cities' response times measure from the time an officer is dispatched to the time they arrive on scene. Peoria, by contrast, measures the time a person calls 911 to the time the officer arrives on scene. This makes comparing city to city difficult.

Peoria's FBI-reported crime data over the past 10 years shows:

Violent crime climbed 67% from 282 in 2010 to 487 in 2020, with aggravated assaults the main driver of that jump.

The city averaged four homicides annually in the decade, with peaks and valleys, from nine homicides in 2012 to three in 2020.

Property crime dropped 42% from 4,630 in 2010 to 2,683 in 2020.

Since property crimes make up the largest portion of crime in the city, Binsbacher is correct when she says that crime has fallen.

Beck, in a Q & A with The Republic, says aggravated assaults are up 30%, homicides are up 333%, and violent crime is up 16%. Overall, crime is up 7.36%. This calculation is flawed because it compares data from previous years to 2021, when the city began measuring crime differently.

Important context: In 2021, Peoria began measuring crime in a new way through the FBI's National Incident-Based Reporting System. That meant crime definitions changed. Peoria Deputy Police Chief Doug Steele gave the following example: Accidental deaths, such as when a drunken driver kills someone in a car accident, did not constitute homicide in the pre-NIBRS system. Now, it does. In other words, more crimes count as homicides than they used to, so it may look like homicides increased, but it's likely just a result of the change in how crime is reported, Steele said.

Parks and open space

Much of north Peoria is open desert, and Binsbacher said she wants to safeguard desert land and expand the city’s trail system so that it connects various developments together and syncs up with county and state trails, too.

“There’s always a threat to open space,” Binsbacher said, adding that much of Peoria’s land is owned by the state and “can be auctioned off to the highest and best use, which in many cases is residential development.”

Beck said he's not against parks, but he questioned the amount the city has spent on it and said parks should be funded through bonds, not the general fund.

Peoria is slated to spend $67.6 million on Paloma Park between the finished Phase 1 and yet-to-begin Phase 2, according to city documents.

Two-thirds of the funding came from voter-approved bonds. The other third came from funds intended for capital infrastructure as well as impact fees charged to commercial and residential developers, according to Perez.

Deputy City Manager Andy Granger said the city has paused the park's second phase, however, saying it will pick up again once construction costs go down.

Once parks are built, Peoria operates and maintains them largely via its general fund operating budget. The current budget earmarks $19 million, or about 7%, of its general fund for parks and recreation.

By comparison, neighboring Surprise spends nearly the same, with 35% of its general fund going toward police and fire and 8% going toward parks and recreation.

Transportation

Binsbacher wants to expand public transportation, connecting residents from one part of town to the other. She’d start by revamping programs that were just on the precipice before COVID-19 hit.

POGO, the city’s circulator bus pilot program, was stifled by the pandemic but is still operating, Binsbacher said. She’d like to work on increasing ridership and then review how residents liked it to determine if it should be expanded and made permanent.

Binsbacher also is interested in bringing back the RoboRide pilot program. A partnership between Peoria, the Maricopa Association of Governments and autonomous vehicle company Beep, the program provided free rides in an electric, autonomous bus to locations in the P83 Entertainment District and to medical facilities near Plaza del Rio Boulevard and Thunderbird Road, west of Loop 101.

“The idea (was) … to get them back and forth to doctors' appointments, grocery stores and critical transportation needs. … I would like to see us move forward with that in the near future,” she said.

Jobs

Beck said a city-built airport, similar to Phoenix's 500-acre Deer Valley Airport, could “drive approximately $2.5 billion of economic impact just in that one area alone and about 15,000 to 20,000 jobs.”

Beck said he'd release a full strategy reviewed by local economist Jim Rounds over the summer, but has yet to do so. Beck told The Republic in October that he was working on it.

He's eyeing the shuttered Turf Soaring School, along Lake Pleasant Parkway north of Loop 303.

Beck said he previously contemplated opening the airport privately with investor Tony Feiter of Levine Investments, but he abandoned the idea when he decided to run for mayor. Feiter donated $2,000 to Beck’s campaign.

If the city were to open an airport, it would need to contract out for the design and construction through a competitive bidding process.

Beyond the airport idea, Beck said he wanted to revamp Peoria’s culture to be more business friendly. He wants to “cut red tape” and hire more employees to speed up the permitting processes.

Binsbacher has likewise said she wants to bring more jobs to the city. She'd like the city to work more on showcasing the existing workforce in Peoria and the high quality of life to prospective companies. Doing this, she says, will attract employers that provide high quality jobs and pay high wages.

Light manufacturing, technical operations and medical centers would be her preferred employers, Binsbacher told The Republic. She also would focus on employers that are environmentally friendly and not too water-intensive, she sd.

Reach reporter Taylor Seely at tseely@arizonarepublic.com or 480-476-6116. Follow her on Twitter @taylorseely95 or Instagram @taylor.azc.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: 5 takeaways in the contentious Peoria mayoral race