Patterns of police abuse lurk in complaints that Raleigh settled with cash, critics say

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

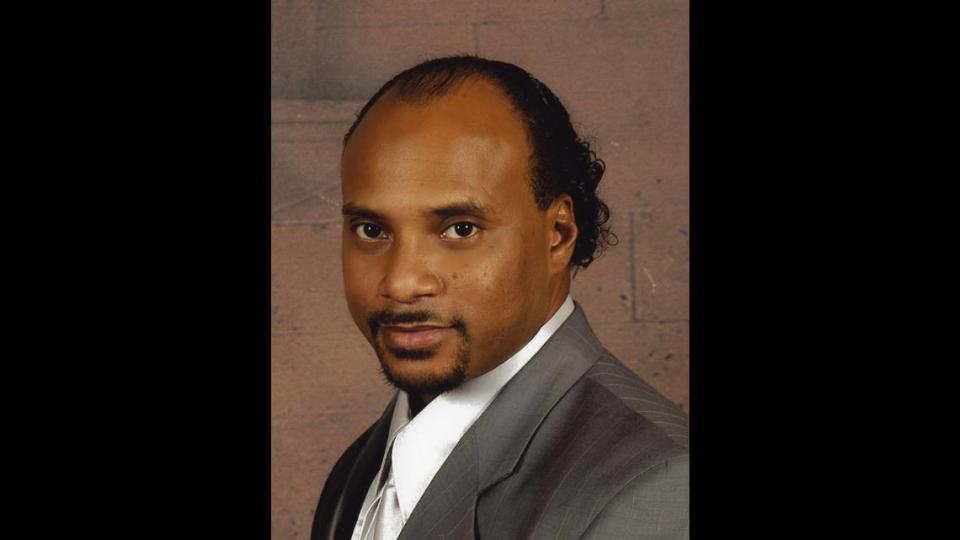

Darryl Williams wriggled under five Raleigh police officers who sat on and around him yelling for him to put his hands behind his back.

“You’re going to get tased again,” Officer Christopher Robinson warned Williams, body-camera footage released by police shows.

After struggling with officers for 2 minutes and being tased at least twice, the 6-foot-2, 300-pound Williams was winded.

“I have heart problems, please,” he pleaded between gasps. “Please.”

“Three-two-one,” Robinson counted before pressing a Taser into Williams’ upper back.

“Ahh. Ahh. Ahhh,” Williams cried out. He writhed as the Taser crackled for seven seconds, the police video shows.

“Please” was his last word before he lost consciousness and officers handcuffed him, at 2 a.m. on Jan. 17, 2023 under flashing neon lights from a nearby sweepstakes outlet and smoke shop.

In less than 10 minutes, police went from questioning Williams and a passenger hanging out in a Southeast Raleigh parking lot to telling EMS to hurry as Williams’ pulse faded.

At age 32, Williams was pronounced dead at WakeMed, but his family believes he died on the pavement from unjustified police violence. Family members acknowledge that Williams ran from police, but that didn’t justify harm done by officers who are supposed to be trained to safely restrain, they say.

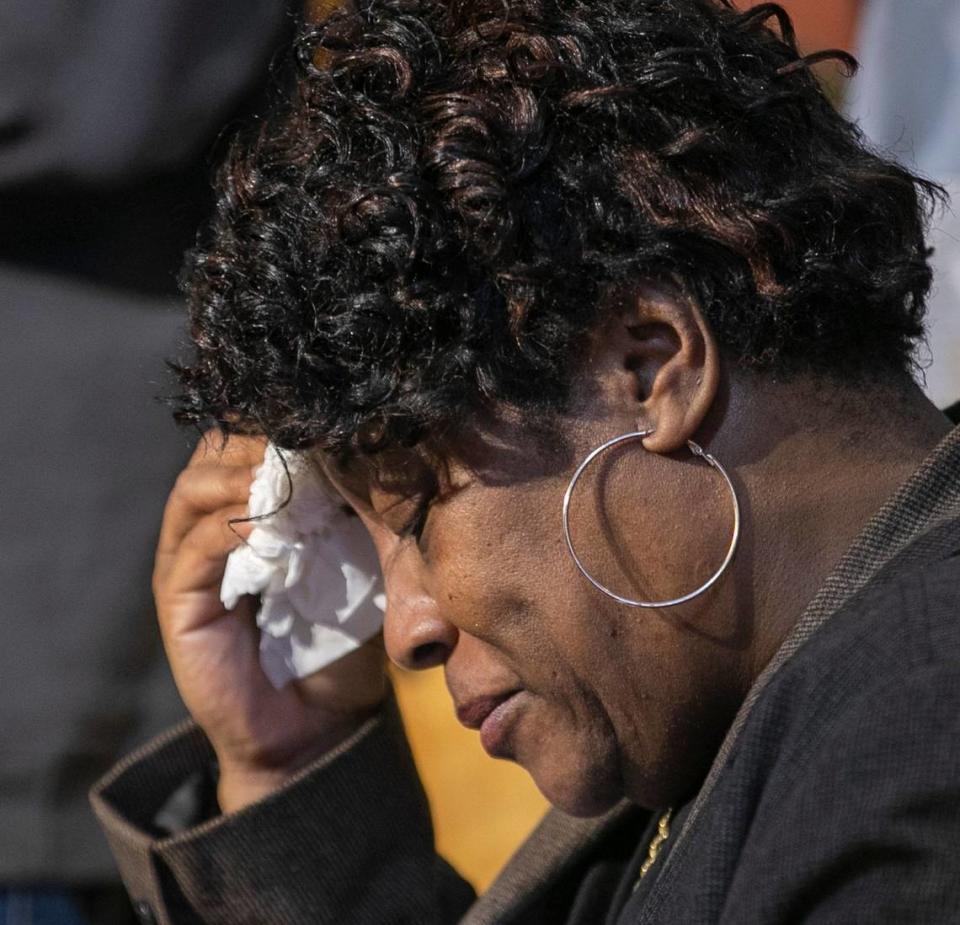

“They killed my son,” Williams’ mother, Sonya said in an interview with The News & Observer. “He would still be here right now had they not did that tasing.”

A pattern of brutality?

Darryl Williams is one on a long list of people accused of nonviolent crimes who ended up dead, injured or traumatized after encounters with Raleigh police in recent years. Just days ago, his family became the latest to file a lawsuit accusing city police of abuse as a result.

If people can find an attorney willing to represent them, holding police accountable through civil lawsuits is an uphill battle. State and federal laws give officers broad authority to use force and set a high bar to prove police behaved inappropriately.

Despite those barriers, the City of Raleigh since 2012 spent $4.3 million to settle 17 lawsuits and threats of lawsuits, with dozens of people alleging police misconduct, a News & Observer investigation found.

The settlements aren’t indictments of all Raleigh police officers. Each year, police in North Carolina’s capital city arrest thousands and have hundreds of thousands of interactions. Only a small number of encounters result in officers using physical force or drawing complaints.

But similarities in the complaints and their rising costs signal a serious problem in how some officers treat people they are hired to serve, local civil rights lawyers say. Most of the people who received city payouts in settlements were Black.

Rarely publicly announced, some payouts kept complaints against police out of public courtrooms. Details available for 16 of the settled complaints, brought by 46 people, allege multiple types of problematic police behavior. But three weighty accusations are repeated:

▪ Excessive force: From 2013 to 2023, the city has settled five cases alleging excessive use of force in incidents that go back to 2010. Those cases include police shooting and killing men with disabilities in 2019 and 2020, officers beating a man who was possibly experiencing heat stroke in 2018, and an officer shattering a homeless man’s leg while arresting him on public intoxication charges in 2010. No convictions followed the arrests of those who survived.

▪ Wrongful arrests: From 2014 to 2022, the city has settled seven cases involving 22 people who contended wrongful arrests going back to 2013. The lawsuits say Raleigh police from 2019 to 2020 wrongly arrested more than a dozen people on drug charges based on accusations from a corrupt confidential informant. Settled cases allege that police in 2020 wrongly arrested a 17-year-old during an afternoon protest, and in 2013 did the same to a Black man complaining about a white officer’s treatment of a Black Enloe High School student.

▪ Improper searches, home invasions: From 2012 to 2023, the city settled three cases accusing police of wrongful searches going back to 2010. Three families said police traumatized them when they raided two apartments in 2020, holding a mother, teens and others at gunpoint based on a warrant with the wrong address. Another case alleges a man was terrified and traumatized by officers when they took him to a police office at a strip mall and made him take off his clothes to be searched.

“These lawsuits and settlements reflect a pattern and practice of excessive force and overpolicing of poor people of color in the City of Raleigh. Many of these police interactions should never have occurred,” said Abe Rubert-Schewel, who has represented 28 individuals who settled complaints against Raleigh police.

In court documents, sworn depositions and speeches to City Council, current and former Raleigh police chiefs as well as city attorneys have defended officers’ actions described in the settled lawsuits and complaints, often saying police acted appropriately in responding to aggressive behavior.

The News & Observer since January has requested interviews with Police Chief Estella Patterson, Mayor Mary-Ann Baldwin and City Manager Marchell Adams-David to discuss the many allegations in the settled lawsuits, most of which The N&O is making public for the first time.

Patterson responded in writing saying she could not discuss specific cases but said that allegations against officers are taken seriously and investigated thoroughly. Officers often face dangerous, rapidly evolving situations, she stressed.

“I am committed to making sure we provide them with the training and equipment to facilitate safe and effective resolutions in dynamic circumstances,” Patterson wrote.

The city’s communication director, Robin Deacle, said Baldwin couldn’t talk about lawsuits or settlements. She also sent a written statement.

“Raleigh faces real challenges from its rapid growth. It is our job to make sure that our public safety workers have the training and resources needed to build trust with the community and to keep it safe,” the statement reads.

Over the years, the city and police have taken steps to reduce risks of police misconduct and address community members’ concerns, city officials say. That has included requiring that officers wear body cameras in 2018, establishing a Raleigh Police Advisory Board, and banning choke holds in 2020. Other changes include rolling out a social services unit and a de-escalation policy in 2022.

But lawsuits and settlements keep coming.

Wrongful arrest

When a person dies during a confrontation with police, it makes headlines, as the death of Darryl Williams did in 2023.

But the settlements also detail nonfatal assaults that take physical and psychological tolls.

A wrongful arrest claim submitted by Isaac Horton IV, owner of Oak City Fish and Chips food trucks and restaurants in Raleigh, is one.

Police arrested Horton and his then business partner Omeze Nwankwo in the summer of 2014 as they attended a party at the Noir nightclub in Glenwood South, according to a lawsuit filed in 2015. Their charges included blocking a sidewalk and resisting arrest.

Horton had stopped by the Noir party at the invitation of the host, who he had mentored. After 20 minutes, Horton stepped outside to call a cab after a long day at his food truck, he said.

Working off duty for the club, Raleigh police Detective Robert Pike approached Horton and aggressively demanded that he leave the area, Horton’s lawsuit claimed. As Nwankwo and others defended Horton, Pike asked Nwankwo to come to the front of the nightclub, where Pike threw him onto a car and arrested him while two other on-duty officers held him down, the lawsuit states.

Nwankwo was charged with resisting arrest while being cited for blocking a sidewalk. Pike locked plastic “flex cuffs” on Nwankwo, which the officer later tightened against manufacturer’s recommendations, leaving Nwankwo in severe pain and damage to his nerve, according to the lawsuit.

Horton said he followed his business partner after hitting the video record button on his phone. An unnamed officer struck Horton in the face while throwing his phone in the street, then charged him with trespassing, according to the lawsuit.

An employee had asked Pike to prevent the men from re-entering the nightclub they had been kicked out for disruptive conduct, city attorneys wrote in court documents responding to the lawsuit.

Nwankwo refused to leave and “verbally” abused Pike, city attorneys wrote in court documents answering the lawsuit. Horton was arrested after he refused to keep a safe distance as police arrested Nwankwo, city attorneys wrote.

But Horton says the officers had confused him and Nwankwo with two inebriated brothers, also Black men, who had been drinking at the bar and stepped out the back.

Horton, who had never been to jail, said the negative impact of the episode extended beyond the dehumanizing experience, Nwankwo’s injured wrists or the year Horton refused to drive because he didn’t want to risk another encounter with police. “It took me a year to beat the false trumped-up charges,” he said.

Horton paid an attorney $5,000 and missed 12 days of work to meet with his attorney and attend hearings, which were continued again and again.

In 2016, the city paid the men $50,000, an outcome possible because they had resources, flexibility as business owners and videos of the incident, stressed Horton, an eighth-generation member of a prominent Raleigh family.

The majority of Americans live paycheck to paycheck, he pointed out. Even if they kept their job after being arrested, taking 12 days away from work would gouge their pay and paid time off.

“These are things that are very subtle nuances,” he said. “That, you know, no one really kind of thinks about.”

Dawn Blagrove, executive director of civil rights organization Emancipate NC, agrees. Lawsuits filed are “literally just the tip of the iceberg,” she said.

17 settlements involving 47 people

Still, lawsuits or threats to file lawsuits are one way to push for change when city officials rarely acknowledge that police overstep their powers, say attorneys and police reform advocates in Raleigh.

Since 2012, the city’s annual payouts have increased from thousands of dollars to millions, with the 17 cases confirmed by The News & Observer totaling nearly $4.3 million.

One of the most recent paid settlements, revealed by The N&O in November, was $1.25 million paid to the estate of Soheil Mojarrad in 2023. Mojarrad was shot and killed by a Raleigh police officer in April 2019. This is the largest settlement documented by The News & Observer linked to one person’s experience with Raleigh police.

Seven years before he was killed, Mojarrad was hit by a pickup truck on an Asheville road, resulting in a traumatic brain injury that left him with seizures, struggles to communicate and uncertainty at times about understanding what was going on around him, said his brother, Siavash Mojarrad.

In April 2019, Officer Brett Edwards went looking for Mojorrad after his department got a call that he’d stolen a cell phone plugged into a wall at a Sheetz on New Bern Avenue around 8:20 p.m.

The two men faced off in a grassy area near a shopping center, and Mojarrad pulled a pocket knife from his pocket and advanced toward him several times, Edwards said in a police report. Two witnesses say they didn’t see a knife in his hand, according to the complaint, or see Mojarrad move toward Edwards, according to the lawsuit.

The officer fired 11 shots, eight of which hit Mojarrad, who collapsed and was dead by the time another officer arrived, the lawsuit claims.

Mojarrad’s family disputes that he had a knife, and no DNA evidence confirmed that a knife found near his hand belonged to him, according to the family’s lawsuit. But even if he did, family members say, Edwards said Mojarrad was 20 feet away. The officer could have retreated, but didn’t.

In court documents, Raleigh police say Edwards felt threatened. They noted that someone can run 20 feet in seconds, and officers shouldn’t put themselves at risk. The family say that a trained police officer should have done more to de-escalate the situation.

In May 2019, a month after Edwards shot Mojarrad, former Police Chief Cassandra Deck-Brown told the City Council that Raleigh police aren’t perfect but they strive to recognize their shortcomings. But the community also needs to take some accountability, she stressed.

“When we talk about accountability, our community has a responsibility to be accountable for their own actions as well,” she said.

In depositions and court documents in the Mojarrad case, Deck-Brown, other officers and city attorneys also have argued that the Raleigh department uses best practices to train and monitor officers.

One example is a system that flags officers who have used force three or four times a quarter, Deck-Brown said during a deposition in October 2021. The police department has never identified a problematic problem, she said.

More training?

Raleigh police need more de-escalation training, and they need to be tested on related training to ensure they understand the information, said Cate Edwards, the Raleigh attorney who represented Mojarrad’s family

Police practices that allow police to escalate force when individuals don’t comply with commands or allow themselves to be detained don’t take into account people who don’t trust police or are experiencing a mental illness or health issue, Edwards said.

“It just seems like there would be a better way,” Edwards said about the arrest of Mojarrad, who initially ran from police. “But their only way was just to escalate, escalate, escalate.”

Officer Edwards received a written reprimand for not turning on his body-camera during the shooting, which is a violation of the department’s policies, according to a deposition Cate Edwards took of then Raleigh Deputy Chief Todd Jordan.

But before the $1.25 million settlement with Mojarrad’s family, officer Edwards’ department held his actions that day as an example of appropriate policing and asked the officer to speak to training classes about his experience and actions, Raleigh Capt. Peter Rowland testified in a deposition.

Beyond the settlements

Lawyers and community members say the settled complaints bring evidence of a pattern of police mistreatment for years.

Two settled lawsuits referred to nine people who died and two who had been injured from 1991 to 2020 after encounters with police officers, for instance. Half of those people appeared to be suffering from mental health or physical issues, according to the settled lawsuits and interviews with family members.

While the city has acknowledged police didn’t follow policies in some of the settled cases, including not turning on a body camera or arresting someone without probable cause, City of Raleigh attorneys contended officers used force appropriately in all but one incident.

Officials in that case fired Officer Michelle Peele. While working off duty she shot and killed Nyles Arrington while he attempted to take the officer’s car in 2005 at La Rosa Linda, a now closed club on New Bern Avenue. She didn’t follow policy that forbids officers shooting at a moving vehicle except in certain circumstances, the court documents state.

City attorneys defended officers who repeatedly shocked Thomas Jeffrey Sadler, a man with a history of mental illness, after neighbors reported bizarre behavior in 2013. City attorneys wrote in a court document in 2021 that officers used a Taser on Sadler more than 11 times. But an internal review concluded there were no policy violations or unethical behavior.

Corye Dunn, director of public policy for Disability Rights North Carolina, said that answer doesn’t make sense to her.

“I would ask that community members in assessing what policy should be, really consider what they would want for themselves and their loved ones, if they were to experience a crisis like this,” she said.

Last spring, the criminal justice reform group Emancipate NC asked the U.S. Department of Justice in a letter to investigate what they say is the Raleigh Police Department’s patterns of civil rights violations. The next month, Emancipate met with federal officials to outline their concerns.

The letter points to two recent police killings, and accused Raleigh police of releasing “victim blaming propaganda” afterward.

It cites the death of Daniel Turcios, 44, who police shot and killed in front of his two sons and wife in daylight after he crashed his car on Interstate 440 in January 2022. Police suggested he was intoxicated and pulled out a knife and threatened police, the letter states. The autopsy showed there were no drugs or alcohol in Turcios’s system. His family contends the father, who did not speak English, was disoriented after the wreck and didn’t pose a threat with the small knife.

That same year police killed Reuel Rodriguez-Nunez, 37, who police shot while he was setting cars on fire and throwing plastic cups of lit gasoline toward officers in the parking lot at a police substation in Southeast Raleigh. Rodriguez-Nunez was experiencing a mental health crisis, and the situation escalated when an officer approached the man and told him to throw the lit cup he had in his hand, Reuel Rodriguez-Nunez’s brother, Jasiel, said.

“Go ahead motherf—--, do it,” Master Police Officer P.W. Coates said before Rodriguez-Nunez threw a lit cup in the officers’ direction and police opened fire, according to police body-camera video.

In both cases, Wake County District Attorney Lorrin Freeman ruled the officers were justified in their use of force and the cases didn’t merit criminal charges.

In February, the U.S. Department of Justice selected Raleigh to participate in a National Public Safety Partnership, which includes training on constitutional and community policing. Communities apply to participate.

“With Raleigh’s inclusion in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Public Safety Partnership, we look forward to tapping federal resources and national expertise to make Raleigh one of the safest cities in the country,” Baldwin, the mayor, said in her written response to questions about the settlements.

Some community members have complained about some Raleigh predatory policing practices for years.

“The style of policing is almost set up to be fatal,” said Kimberly D. Muktarian, president of Save Our Sons, which works with youth and others in the Southeast Raleigh community.

Members of her community want to be treated with civility and care, Muktarian said. They want officers to call 911 right away if they see someone, like Williams, experiencing medical distress.

“They just don’t for our people,” she said. “That’s a use of force as well.”

The latest lawsuit

The lawsuit accusing Raleigh police of using excessive force against Darryl Williams the night he died in that Raleigh parking lot was filed days ago. But his mother said she has lived with anger and suspicions for 14 long months.

Hours after Williams’ death, detectives came to the door of the Southeast Raleigh home Sonya Williams shares with her mother to report that her son had died in police custody. They didn’t share any other details, the mother said.

“Why can’t you tell me how my son died?” she said she recalled asking them.

About a week later, two detectives knocked on the door again and told her that Darryl Williams died after an officer shocked him with a Taser, but didn’t say how many times.

Sonya Williams soon saw the attack for herself, in a police conference room with her cousin at her side. She watched the fatal scuffle with police on a big drop-down screen six times, each from a different Raleigh police officer’s body cameras.

She saw two officers patrolling the area on Rock Quarry Road near Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Officer Robinson approached Darryl Williams, who sat in the driver seat in a black Mercedes-Benz. After he shined his flashlight on what they said was an open container of alcohol and a bag of marijuana, Robinson asked the men to step out of the car. Robinson searched Williams and found a folded dollar bill in his pocket that had what police officials said looked like cocaine on it, Raleigh police wrote in a report on Williams’ death.

Robinson grabbed Williams’ wrist and told him he was under arrest. Williams ran. An officer shot his Taser, sending two thin metal wires with prongs into Williams.

Williams crashed into garbage bags and cans piled next to a building, bottles clinking as the struggle continued. Williams pulled free and ran a few feet before falling. Officers followed, surrounded him and yelled for him to put his hands behind his back.

One officer had a knee on his back and another had a knee on his arm for 30 seconds after a Taser discharge surged into his body for a third time, an autopsy states. The newly filed lawsuit contends he was actually shocked by a Taser six times, not three.

Officers handcuffed Williams, then rolled him on his side. He fell still.

“Is he still good?” one officer asked, concerned whether Williams was still breathing. They dismissed the concern after another officer said he felt his pulse, according to body camera footage and the autopsy report.

After Williams was handcuffed, police found two guns in the Mercedes-Benz, including one that was reported stolen, police said.

An autopsy said Williams ingesting cocaine contributed to his death, as did his fight with the police who used Tasers to restrain him.

“After our fight with him, he passed out,” one officer says to another in body camera footage.

Raleigh police policies say that officers should only discharge a Taser on someone who is running away if the person poses an immediate threat to themselves or others. They also say officers shouldn’t use a Taser in drive stun mode, such as when they pressed the Taser directly into Williams’ back twice within minutes, because it may not be an effective tool and may actually escalate someone’s resistance.

The policy also points out that officers should be aware that there is a higher risk of sudden death when discharging a Taser on people under the influence of drugs.

Five minutes after Williams fell still, officers started CPR as his pulse faded. Williams’ hands remained handcuffed the entire time, according to the autopsy.

Officers were guarding her immobile son while they should have been helping him, Sonya Williams said.

“It was just so heartbreaking,” she said. “I just cried. I just cried.”

Virginia Bridges covers criminal justice in the Triangle and across North Carolina for The News & Observer. Her work is produced with financial support from the nonprofit The Just Trust. The N&O maintains full editorial control of its journalism.