‘Overwhelmed’: Kevin Strickland plans to take one day at a time after wrongful conviction

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

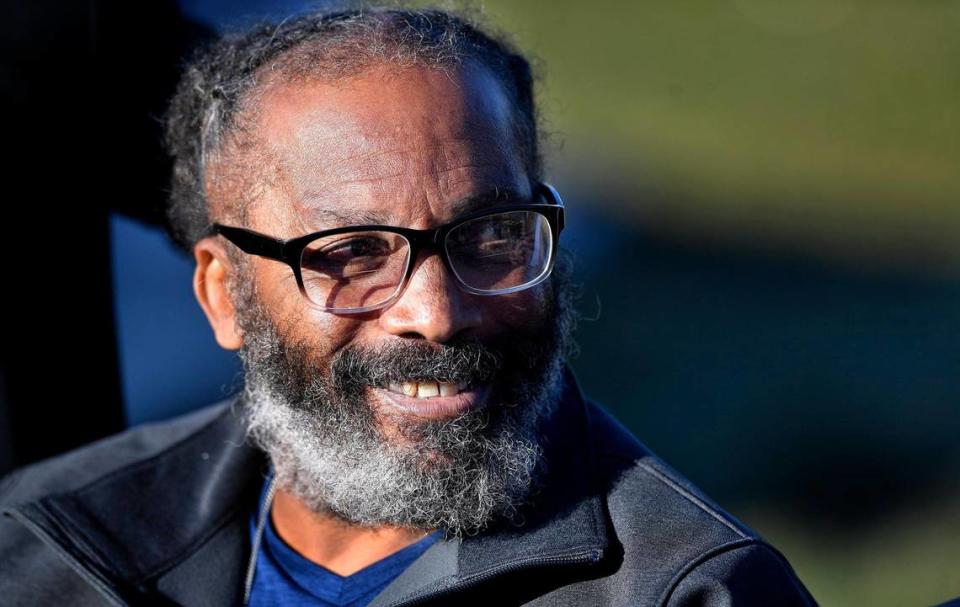

After he was freed in a highly-publicized exoneration, Kevin Strickland said he is looking forward to coming and going when he pleases, and being able to eat when he wants.

Just living. One day at a time — without supervision.

Strickland, 62, was released Tuesday from the Western Missouri Correctional Center in Cameron after a judge granted Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker’s motion to exonerate him in a 1978 triple murder that he has always said he did not commit.

After he was pushed out of the prison in a wheelchair by one of his attorneys, Strickland told reporters and cameras crews gathered across the street that he learned of his exoneration through a news alert that flashed across a television. Before then, he had been watching a soap opera, he said. Other prisoners started hollering and banging on the walls.

He was going home.

Judge James Welsh exonerated Strickland, who was arrested when he was 18, and ordered his immediate release. It confirmed Strickland, who spent more than 40 years behind bars, suffered the longest wrongful conviction in Missouri history.

Asked what he thought about the criminal justice system, Strickland told reporters it “needs to be torn down and redone.”

“It don’t work,” he said. “I mean, it work here in the long run, but it took 43 years to get here.”

In a call with The Star, as he sat in a car with the legal team that helped free him, Strickland said he was ecstatic, fearful and overwhelmed. He thanked anyone who prayed for him. He meant it, he said. He’s grateful.

Strickland has said he does not intend to live in Missouri, which will not compensate him for his 42 years in its prisons because of its narrow compensation law. He has never seen the ocean and wants to go somewhere warm with a coastline.

Maybe California or Florida, he has imagined, away from the cold.

“I want to feel the power of the ocean,” Strickland has said. “Yeah, I want to do that.”

On Strickland’s car ride home, one of his attorneys, Robert Hoffman, said he was overjoyed by the judge’s ruling. But he said the criminal justice system has a long way to go. He noted that Strickland’s case illustrates all the challenges an innocent prisoner faces.

“Even after all the support he had and with the assistance of the prosecutor, we still had to fight for months and months to achieve this result,” he said. “It’s just way too easy to put someone in prison for something they didn’t do and way too hard to get him out.”

For Strickland, the road to exoneration was a long one.

Decades in Missouri prisons

On the day Strickland was arrested in April 1978, his girlfriend dropped their 7-week-old daughter off at his family’s home on Jackson Ave. It was going to be his first time watching her.

Strickland, who dropped out of Southeast High School, had applied to join the military, he has said. He figured he could see the world and marry his girlfriend that way.

But before his girlfriend left, a relative glanced outside and hollered: “It’s the police.” Two officers, emerging from an unmarked squad car, came to the door. They were there to arrest Strickland for a shooting that left three people dead the night before.

Perplexed, Strickland was handcuffed and taken downtown.

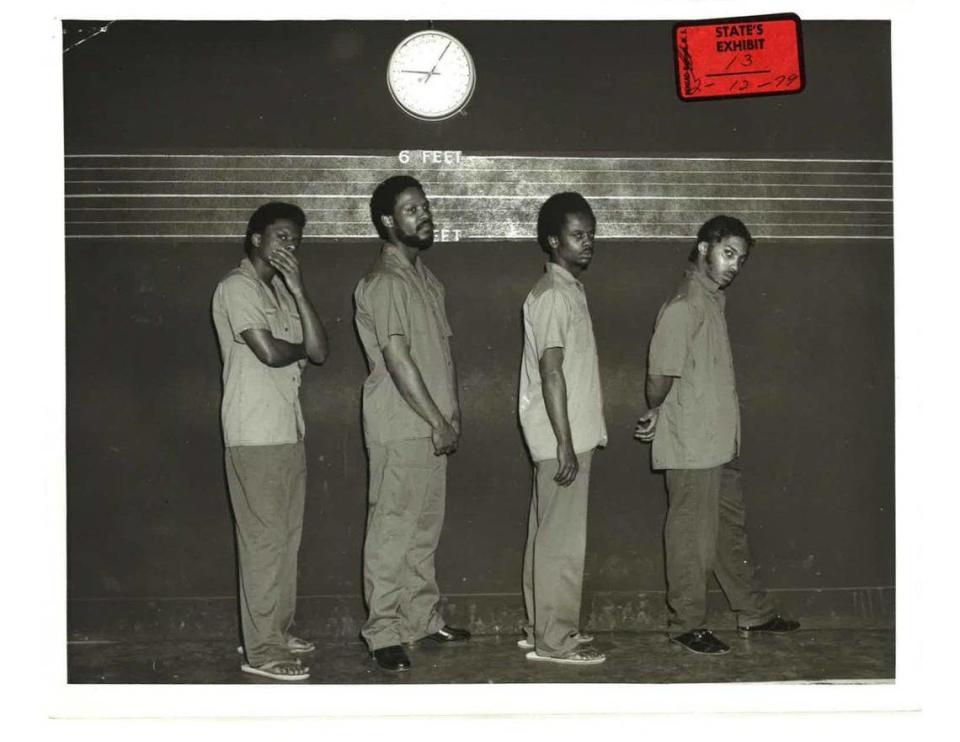

The case against Strickland was “thin from its inception” and relied almost entirely on the testimony of a traumatized woman who was shot during the murders, prosecutors now say.

Strickland’s first trial in 1979 ended in a hung jury of 11 to one, with the only Black juror holding out for acquittal. He was convicted two months later by an all-white jury, which his attorneys say was by design.

Prosecutors waived the death penalty. He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for 50 years. He was shipped off to the Missouri State Penitentiary. Standing 5-foot-3 and weighing 140 pounds, he had to fend for himself.

The case against Strickland, however, began to crumble almost immediately. Four months after he was convicted, a man named Vincent Bell pleaded guilty and insisted that Strickland was not with him and three other suspects during the murders. Bell testified that the lone eyewitness to the killings wrongly identified Strickland and mistook him for another teenager.

“I’m telling you the truth today that Kevin Strickland wasn’t there at the house that day,” Bell testified. “I’m telling the state and the society out there right now Kevin Strickland wasn’t there at that house.”

Relatives of the eyewitness have said she was pressured into identifying Strickland by detectives, including one who has been called a “cowboy” who later killed his wife and then took his own life.

On Tuesday, Strickland said he did not have hard feelings for the eyewitness. Those are reserved for the system itself, he said.

At least two men who were imprisoned for crimes they did not commit in Missouri were there to welcome Strickland home. As was Baker, whose office spent months and many resources trying to free him.

“To say we’re extremely pleased and grateful is an understatement,” Baker said in a statement earlier in the day. “This brings justice — finally — to a man who has tragically suffered so, so greatly as a result of this wrongful conviction.”

Relying on strangers

Because he was not exonerated through a specific DNA testing statute, Strickland will not be compensated by the state of Missouri for his wrongful conviction.

Its compensation law is very narrow, legal experts say. Few exonerees ever see a dime.

His attorneys set up an online fundraiser, which had raised about $37,000 by Tuesday morning, to help him pay for basic necessities. By the afternoon, once news broke of his release, it had increased to more than $115,000.

That’s about $2,700 for each year he wrongly spent behind bars, where he was locked up, he has said, with “murderers, rapists, child molesters, arsonists.”

The federal standard for compensation is $50,000 for each year of wrongful imprisonment. The majority of states with a compensation law, including Indiana and Alabama, provide that or more. In Texas, exonerees are eligible to get $80,000 for each year behind bars.

But in Missouri, the wrongly convicted are almost always spit out of the system with nothing.

Strickland’s innocence was the focus of a September 2020 investigation by The Star, which interviewed more than 20 people, including two men who admitted guilt and swore Strickland was not with them and two other accomplices during the killings. The Star also reported that the eyewitness, whose testimony was paramount in the case against Strickland, told relatives she wanted to recant her identification of him and believed she helped send the wrong teenager to prison.

Jackson County prosecutors began reviewing Strickland’s conviction in November 2020 after speaking with his lawyers and reviewing The Star’s investigation. Following a months-long review of the case, Baker’s office in May announced that Strickland is “factually innocent” in the April 25, 1978, triple murder at 6934 S. Benton Avenue in Kansas City and should be freed immediately.

A host of officials who called for Strickland’s exoneration cheered his release. That included Kansas City Councilman Lee Barnes, 5th District at-large, who previously urged Missouri Gov. Mike Parson to pardon Strickland, which he did not.

Barnes agonized over whether the judge “would do the right thing.” He called Strickland’s exoneration “a tremendous event and day for him and the community.”

“As a country, we need to reexamine what our justice system looks like,” Barnes told The Star. “Do I think it’s justice that he’s finally being freed from a crime he didn’t commit? I don’t know if that’s fully called justice, but at this moment in time, it is a great thing that he’s finally exonerated.”

In total, Strickland spent more than 42 years and 4 months behind bars — or 15,487 days.

Relatives, including Strickland’s older brother, L.R., were ecstatic to learn of Strickland’s exoneration. The last time they saw him outside of prison walls was when those two officers came to pick him up back in 1978.

“I’m so happy for my brother,” L.R. said. “This is like the blessing of life itself.”