One massive tragedy of World War II still being ignored

Excerpt from “Under the Java Moon: A Novel of World War II,” Shadow Mountain (2023).

“Will I ever see Papa again?” Marie Vischer asked her mother, while perched on the wilting fence in front of the house she’d been sharing with over 100 other women and children, in the heart of the Tjideng Women’s Camp on Java Island, Indonesia.

It had been three years since Marie and her pregnant mother, toddler brother and elderly grandmother were forced into an internment camp by the invading Japanese army. Three years since she’d had a full meal. Three years since her father left to join the conflict with a group of Dutch Navy officers and their small warship was torpedoed by a Japanese destroyer.

The war had finally ended, but the Dutch prisoners weren’t allowed to leave the camp yet. And the Japanese soldiers had remained to protect them from civil unrest outside the camp.

“We have to keep faith, Rita,” Mother murmured, using her childhood nickname.

But Marie heard the crack of her voice, edged with grief that loomed dark with each day passing without Papa. Marie examined the faces of the men and boys hobbling and limping into camp, their gaunt faces mapped with three years of war, skeletons of their former selves.

Would she even recognize Papa? Would he recognize her?

Could she hope that he was still alive? Every day she checked the list that the British Red Cross sent to the internment camps throughout the island of Java.

His name had yet to be on it.

A man with scarecrow-thin legs and brown eyes like her father embraced a different woman, a different child. Weeping. Not her father, then.

They’d made it this far. Marie, Mama, Georgie and Robbie. Defying all odds against diseases like malaria, the mumps, dysentery, measles, whooping cough and tropical sores. Not to mention the hourslong roll calls beneath the weight of the merciless sun and suffocating heat, as they paid obeisance to the Japanese commander twice a day. Even then, Marie hadn’t broken.

But never seeing Papa again would be unimaginable.

Another day dragged on without Papa. Another day of endless worry.

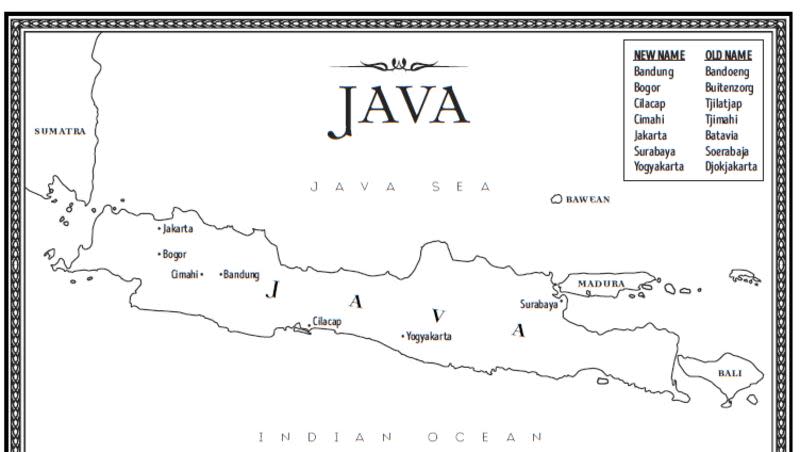

Nearly 80 years have passed since Marie and her family were freed from the prisoner of war camps on Java Island. When the Japanese Imperial army invaded Indonesia (then called the Dutch East Indies) in early 1942, over 100,000 Dutch men, women and children were funneled into prison camps throughout the archipelago. The Dutch plight during World War II in the European arena is well-known as the Netherlands were defeated and subsequently occupied by Nazi forces in May 1940. Lesser-known is what the Dutch people living throughout Indonesia endured for three long years.

In the late 1700s, the Dutch government took over the Dutch East Indies Company — a multinational trading empire — and in the process, Dutch families moved to the islands, seeking private enterprises and dominating economic and political power. When the Mataram empire collapsed, the Dutch officially gained control over the Indonesian islands. Over the next 150 years, more Dutch immigrants arrived in colonial Indonesia, building an infrastructure of industries such as sugar production.

Although Marie’s parents, George and Mary Vischer, were originally from the Netherlands, they lived on Java island as George was stationed there working for the Royal Packet Navigation Company, or KPM. In 1939, at the beginning of WWII, Marie’s father, George Vischer, a chief engineer officer for KPM, was mobilized into the Dutch Navy. Yet their island remained peaceful for the most part over the next couple of years.

Born in Indonesia, Marie’s early childhood was filled with trips to the market with her Oma, climbing mango trees, carting around her teddy bear and playing with her little brother Georgie. Her next childhood memories took a darker turn.

Marie was only 5 years old when bombs began to drop on her Laan Trivelli neighborhood. “What I remember most is the living with fear constantly, seeing the bombs fall, getting into the waterlogged miserable dungeon bomb shelter and then fearing we could get bombed anyway.”

The date? December 1941.

When the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor, every Allied country declared war on Japan, including Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands while in exile in London. A half a world away, Dutch citizens throughout the Dutch East Indies ages 18 and up were asked to join the navy, army or air force, entering accelerated military training to defend against Japan’s impending invasion.

Once war was declared between the two nations of Japan and the Netherlands, the Imperial Japanese Army advanced upon the Dutch East Indies. The vulnerable islands were no match for the highly trained Japanese army and their superior battleships and bombers. Within a matter of weeks, after bombing the islands and defeating Allied forces in the Battle of the Java Sea, Japanese soldiers marched onto Java Island.

Marie will never forget “seeing the Japanese army arrive, and the beatings and screaming of the enemy.” She recalls “my very dear mother being beaten up, the constant hunger and hurt stomach, and being locked up in a prison.”

Despite such crippling childhood memories, Marie’s mother never wanted to talk about the war after the family was repatriated back to the Netherlands. The war was over, and there was no use dwelling on a past that couldn’t be changed.

But in recent years, Marie began to slowly change her resolve. “I never thought it was important to share my war experiences,” she said in a recent interview. “My mother said it was best to forget and leave alone. The past is the past, and who wants to read, hear, and know about war and its atrocities? I certainly did not and neither did anyone else who went through it. In my golden years, I realized the world needs to know and hear from real people who survived wars, not history books. First, that war is terrible, secondly that those who are free need to be more grateful, and realize freedom comes with a price tag, and at a great cost.”

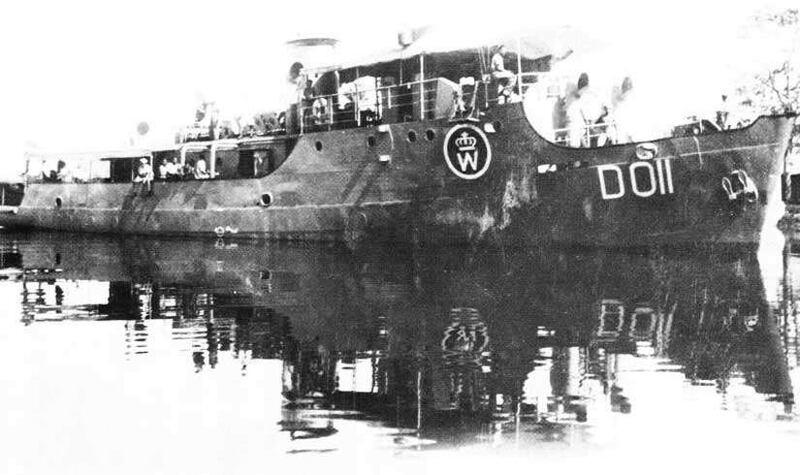

In early 1942, with the Japanese invasion underway, Marie’s father had been sent off the island with a group of Dutch officers with the hopes that they could reach Australia and join the Allied forces in a plan of capturing back the islands. But George Vischer and his fellow officers never made it. On the night they escaped on the minesweeper ship Endeh, they were spotted and torpedoed by a Japanese destroyer. George recalled working in the engineering room when all of a sudden, the orders came through the 1 Main Circuit, “Stop the engines! This is not a drill!”

In the next moment, as the alarm continued to clang, everything disappeared. The engine room. The men around George. The walls. The floor.

George smelled the smoke, heard the flames and saw the burning wreckage of his comrades. Somehow he came away alive with only bruises and a shrapnel injury to his foot. George and the remaining survivors jumped into the Java Sea as torpedoes exploded around them. Soon the minesweeper sunk, leaving the men to grapple over a single dinghy, while floating in an endless stretch of undulating water, among small groups of islands which had been overrun by their enemy. If George and his men weren’t able to get to Australia, they’d be captured, imprisoned and forced into helpless surrender.

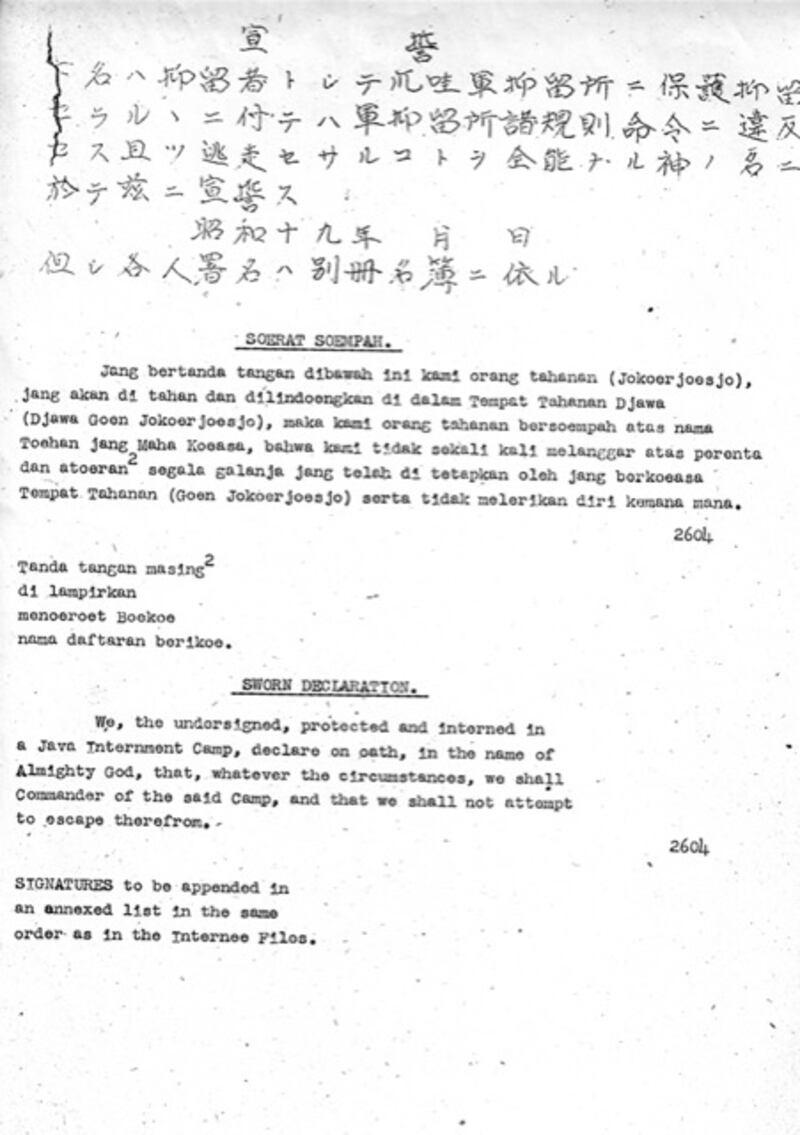

George and his crew spent five days stranded on the Java Sea, seeking an island where they wouldn’t be turned in. But their luck ran out, and they were captured when Indonesian fishermen alerted the Japanese army. “We were not treated badly by the Japanese troops,” George remembered. “We were given food, drink and cigarettes.” Then, the following day, they “were taken to the Kempetai in Batavia and, after interrogation, put in a cell in the Glodok prison with two civilians.”

While George sat huddled in Glodok prison, wondering what had happened to his pregnant wife, mother-in-law and two children, news of all kinds reached him. From the official surrender of the Dutch East Indies government to the Japanese, to the arrest of all European officers, and finally, the rounding up of Dutch women and children.

George would learn that many Indonesians welcomed the Japanese liberators since Japan promised independence to the Indonesians once the war concluded. What George couldn’t know was that millions of Indonesians would be recruited into forced labor. And by the end of the war, 4 million people would die in the Dutch East Indies as a result of famine and forced labor during the Japanese occupation, including 30,000 European civilian deaths.

Also, unbeknownst to George, his family was interned not far from him — at the Tjideng Women’s Camp. The Japanese army had cordoned off neighborhoods and crammed dozens of people into homes. The numbers increased by the month. In early 1942, Tjideng Camp housed 2,600 internees, but by August 1945, more than 10,300 women and children lived at the camp. Living conditions were bleak. The sewer system completely failed, and electricity was nonexistent. Red Cross supplies delivered to the camps rarely made it past the guards, and the food supply quickly dwindled.

Marie recalled, “In the beginning, we received a little rice and seaweed and bread made from starch (or tapioca). You could see through it, and it was hard as a rock. We were only able to chop little pieces at the time and soak it to eat it. My mother made us eat everything we got, no matter how awful it was. The bread and seaweed didn’t last very long, and thereafter we ate one dessert spoonful of rice.”

Tjideng Camp and Glodok Prison Camp were only two camps among the dozens that were scattered across the islands and throughout the Pacific Rim. Conditions and level of work duties varied in the camps. Unfortunately for the young Vischer family, Tjideng Camp was ruled over by the notoriously cruel army commander, Captain Kenichi Sonei, a man who would later be tried and executed for war crimes of exercising systematic terror and mistreating civilian internees.

It was common for work parties to be organized throughout the camps, such as kitchen duty, street sweeping and washing linens for the medical clinic. At Tjideng Camp, crews of children cleared out the sewer trenches and transported the sludge to the ditch that ran beneath the main gate. The teenaged girls at Tjideng were considered to be the strongest group, and they were assigned as pallbearers for the deceased, which meant they transported coffins to the delivery truck that had brought in food to the camp. When the delivery of the coffins stopped, the women built the new coffins from the bamboo poles and tikar panels.

After the Japanese imperial army officially surrendered in September 1945, the soldiers were asked to stay in the camps to protect the Dutch from the rebellions that had risen all over the island as the Indonesians fought for their independence, kicking off the Indonesian National Revolution. Neither the Japanese nor the Dutch were safe outside the camp walls that had once kept the Dutch inside. Now those same walls were protecting the Dutch from the Bersiap uprising.

Months later, in December 1945, Marie’s family secured a spot on the first ship, the Staffordshire, that was transporting civilians out of Indonesia. She fled with her family from Tjideng Camp to the ship docked at Tanjung Priok harbor. “I remember getting on an army truck with canvas over the top with armed guards and hearing shooting with bullets flying everywhere,” Marie said. “Again, I was petrified and did not think we would get to the ship alive. Occasionally I went to lie flat on the truck floor, as I was extremely scared and didn’t want to be shot. For some reason the truck dropped us off quite a long way from the ship. We had to run to the gangway and up the gangway away from the snipers while the guards had their guns ready.”

But her fears didn’t end there. “After safely arriving on board the ship, fear still followed me as I worried about being blown to pieces by the many sea mines that could explode.”

Illness pursued the small family and plagued the thousands of malnourished children as they crowded onto ships transporting them straight into the bitter winter weather on the other side of the world.

Surviving the three years at the internment camp had been no small miracle, and Marie’s grandmother died in camp in 1944. But now the family faced an ocean crossing that was uniquely difficult. Marie and her family arrived along with thousands of refugees in war-torn Holland, seriously ill, and no place to live.

Difficulties continued, and tragedy followed her family with the loss of little Georgie due to pneumonia. Marie was devastated over her brother’s death and spent the next years leading into adulthood seeking answers as to why. ... Why had she survived, why had so many endured so much, and how could she find any happiness with such soul-crushing trauma weighing heavy? Yet slowly, and surely, she discovered peace.

Another family move took Marie to South Africa where she finished school and married Bob Elliott. She and Bob became friends with a couple who invited them to learn more about their faith. Soon, Marie and her husband met with missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Finally, her questions were answered, and she understood that Heavenly Father loves all of His children, including Marie. She realized that she did matter to God and that He knew her and loved her. Marie knew she’d found the truth and was baptized a member of the church in 1971. Her husband Bob wouldn’t get baptized for another seven years, but that didn’t deter Marie. She took her children to church every week, despite the 20-mile distance.

Two years after Bob joined the church, their family traveled to the London temple, where they were sealed together as an eternal family. The joy and happiness that Marie had sought for her entire life became sweeter than she could have ever imagined.

Now, at the age of 86, as a mother, grandmother and great-grandmother, Marie concedes, “There are no winners in a war. We all face hard things in our lives, some of those things may feel insurmountable. In those moments, I’ve learned that happiness comes from within, it cannot be found elsewhere. And, most importantly, I have come to believe what my sweet Oma and wonderful mother lived by — that this life is not the end. That God is real, and I’ve learned to put my trust in Him.”

Heather B. Moore is a USA Today award-winning author of more than 90 publications, including “The Paper Daughters of Chinatown.”