Omicron surge likely to make data on Covid deaths very unreliable – here's why

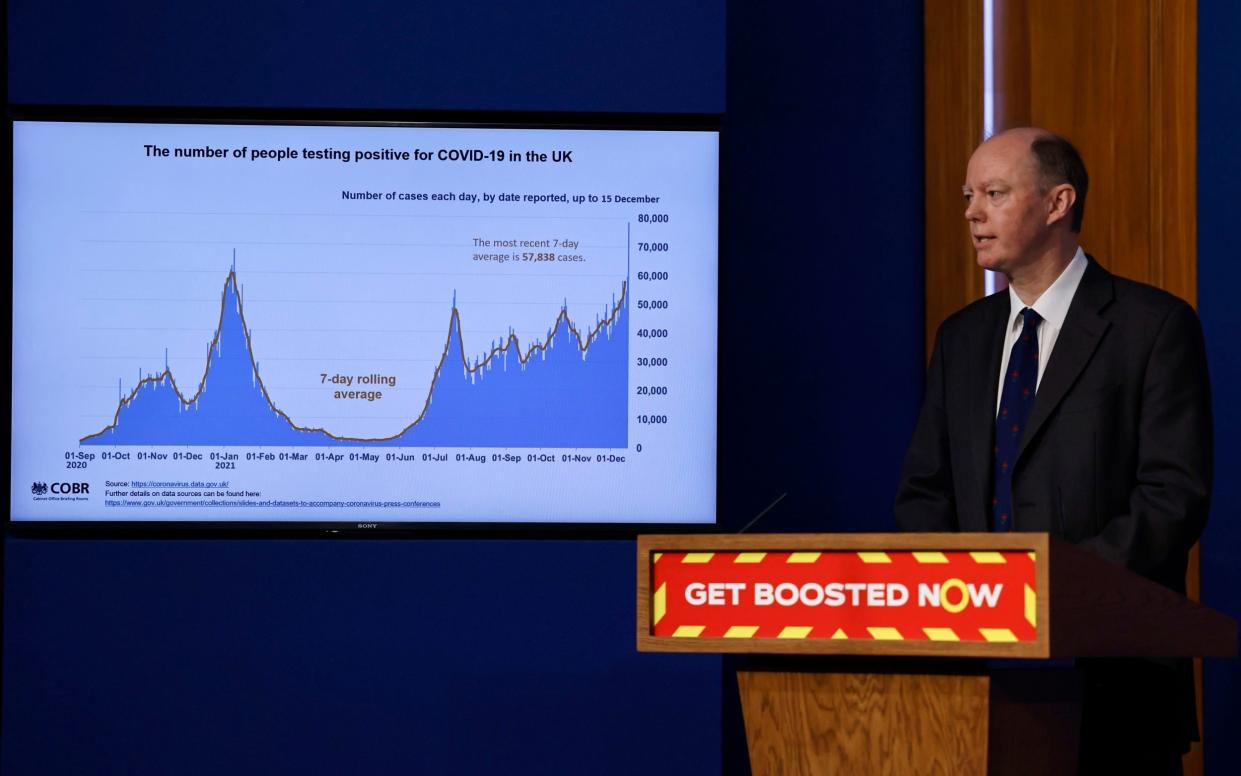

The relentless march of omicron is causing record-breaking case numbers, sparking fears that these will eventually translate into hospital admissions and deaths.

Overnight, the familiar undulating peaks and valleys of the delta wave have taken on a trajectory akin to the north face of the Matterhorn.

But the trouble with such extreme rises is they are likely to skew admissions and deaths figures to such a point that they may become largely useless in helping to drive policy.

Take deaths. Dr Susan Hopkins, chief medical adviser for the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), predicted this week that Britain would see around one million infections a day by the end of the year.

Under modelling by the London School and Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), roughly half the country could be infected with omicron by the spring.

Natural deaths included in Covid data

Deaths are reported as Covid if they occur within 28 days of a positive test. The January death rate is around 0.09 per cent, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). So on a day of one million infections, we would expect 908 of those people to die naturally over the next month, yet currently all would end up in the Covid data.

Under worst case scenarios from the LSHTM, some 34.2 million would be infected up to April - which could see nearly 30,000 natural deaths wrongly reported in the daily Covid figures during that period.

It may be higher than that, because the chances of death increases with age, and although more younger people are currently testing positive for Covid than older people, the chance of an older person dying is more than 10 times greater than the average.

It is worth noting that not all these predicted infections will end up being recorded cases. But most of these natural deaths will occur in hospitals or care homes where patients and residents will have been tested.

The only way to get a true picture is to wait for the ONS to publish death registration data, which breaks down deaths into people who die ‘with’ the disease and those that die ‘from’ it.

But that figure comes about a fortnight late, too late to impact on policy decisions, which must be made quickly. Faced with huge rises in deaths, it may be hard to avoid calls for more restrictions.

Data on hospital admissions will also be perturbed by this glitch. If half of the country catches omicron then the chance of someone testing positive when they go into hospital for any reason will be very high.

Currently around 27 per cent of cases included in the daily admissions figures are patients who tested positive on or after admission rather than being admitted because of the virus. In South Africa that figure is up to 52 per cent in some cases.

Anecdotally, care homes and hospital wards are seeing 50 to 80 per cent of people infected - and these are the most at risk of death from any cause.

‘We need to shift the focus back to excess deaths’

Dr Jason Oke, a senior statistician at the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, at the University of Oxford, said: “It’s a crude estimate and assumes infection is spread evenly across the population, but if by Christmas, 25 per cent of people are infected with Omicron, then it should follow that 25 per cent of all patients admitted to hospital would test positive on entry irrespective of symptomatic illness.”

“Monitoring the figure for people admitted for Covid rather than the total number of admissions would be the way to do it.

“For deaths we need to shift focus back to excess deaths – but with the caveat that this can’t be monitored daily.”

If we really are about to see tens of millions of new infections it is crucial for scientists to make sure that the public understands that even if the omicron wave is extremely mild, we will initially see large numbers of reported deaths, which may eventually be removed from the figures.

It may help quell some of the panic in what is shaping up to be a long, hard winter.