Olympic luger's death triggers memories

KRASNAYA POLYANA, Russia (AP) — Everyone knew the danger. An uneasiness hung in the frosted Canadian air four years ago. Nerves were on edge.

For good reason.

Just hours before the flame was ignited on Feb. 12, 2010 in Vancouver, an otherwise typical morning in the picture-perfect Blackcomb Mountains turned tragic.

Back in Lake Placid, N.Y., Aidan Kelly was on his computer in study hall monitoring the luge competitors as they took their final training runs on the Whistler track before the start of the Winter Olympics.

Without warning, the screen went dark. Disaster, as some feared would happen, came in an unimaginable flash.

In one moment, the sport of luge was forever changed.

"I was that nerd kid who watched everything about luge," said Kelly, a U.S. luger who was just 15 at the time and dreaming of competing in the Olympics. "The guy on the track was going and going and then ... ."

And then Nodar Kumaritashvili, the slider Kelly was watching, was dead.

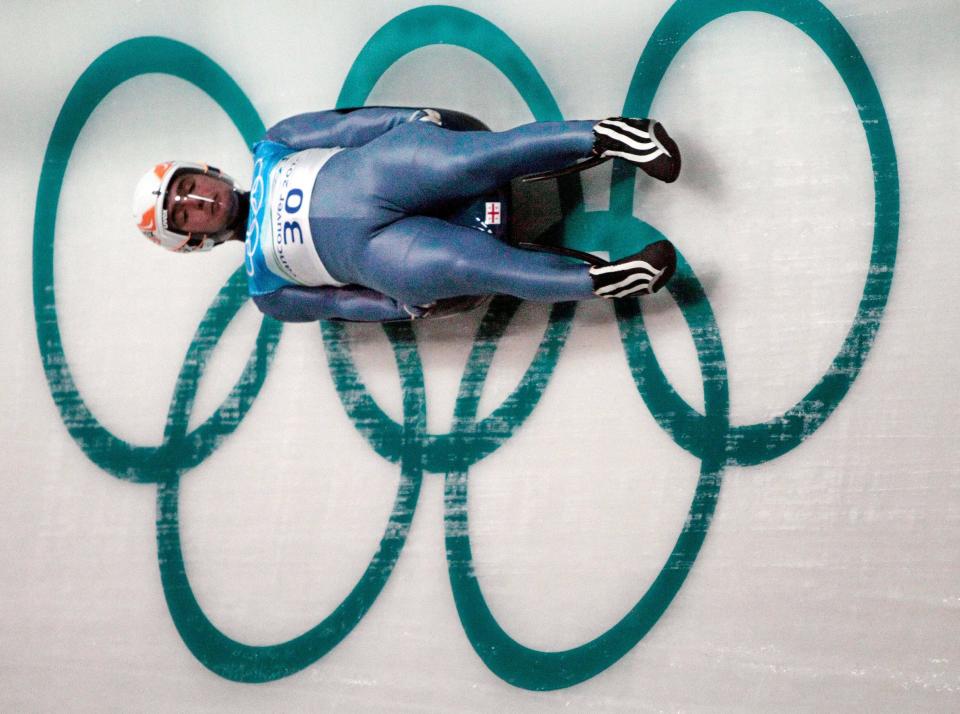

The worst-case scenario, the one foretold by startling speeds, experienced champions crashing during practice, even private predictions from sliding officials, had occurred. Kumaritashvili, an easygoing 21-year-old from a tiny skiing village in war-torn Georgia where his father and uncle raised him to slide, was thrown from his sled traveling at nearly 90 mph, faster than he had ever gone before.

Unable to navigate the last turn of the treacherous track, Kumaritashvili, who had escaped injury during an earlier wreck, went feet-first into one wall, the impact somehow ricocheting his body off the track and the back of his head struck an exposed steel pole within sight of the finish line.

He died instantly.

His death sapped joy from the games, and raised questions about safety and whether the sliding sports — bobsled, skeleton and luge — had pushed the threshold of human performance too far in trying to see how fast highly trained athletes on wind-tunnel-tested, state-of-the-art equipment could go on ice.

"What happened in Vancouver, people can term it as a freak accident but I think it taught a lesson to a lot of people in the sport to take a lot more care when it comes to safety issues," said Indian luger Shiva Keshavan. "That's what they've done here."

To help prevent another serious mishap, organizers for the Sochi Games designed a slower track, but one they believe will still challenge the world's top sliders and drivers.

The Sanki Sliding Center's course, where competition begins Saturday, includes three "uphill" sections that will reduce speeds up to 10 mph. The inclines will put a premium on racers minimizing their mistakes or risk losing even more speed.

Despite the modifications, it's plenty fast and will provide speed-craving athletes the rush they need.

"I do it for the speed and the adrenaline and the G force," said USA-1 bobsled driver Steven Holcomb. "It's fun. You don't get on a rollercoaster because you like the big safety harness. You do it because you like the speed and the adrenaline."

Because that mix can be catastrophic or fatal, Sanki's facility includes a heliport landing pad with an ambulance at the ready in case there's a medical emergency.

Even before the tragedy, Whistler's track had many fearing it might be too dangerous.

Documents showed that Vancouver and international luge officials debated the track's safety for several years. Those concerns grew early in practice sessions when several athletes crashed on the snaking speedway, where the most difficult curve is nicknamed "50-50" for the odds a slider would emerge unscathed.

The day before Kumaritashvili's horrifying crash, a Romanian luger was knocked unconscious and had to be strapped to a backboard and taken to an onsite medical facility.

Something wasn't right, and athletes worried.

"I think they are pushing it a little too much," a shaken Hannah Campbell-Pegg of Australia said after leaving the track following a harrowing practice run. "To what extent are we just little lemmings that they just throw down a track and we're crash-test dummies? I mean, this is our lives."

The next morning, Italy's Armin Zoeggeler, a five-time Olympic medalist back in Sochi at age 40, flipped his sled.

Kumaritashvili's deadly descent soon followed.

As he emerged from Curve 15, Kumaritashvili was moving too fast to handle the sweeping final bend and he was propelled outside the track and struck the beam, which was not padded and may not have protected him even if it had been. The next day, when sliding resumed, padding was there.

In the rush to assess blame, some pointed to Kumaritashvili's inexperience. However, that argument was weakened by some of sliding's superstars.

"It was challenging because the corners were so close together and it was so fast you couldn't process them quick enough," said Holcomb, who enters the Sochi Games favored to defend his gold medal in four-man. "Drivers were like, 'Holy cow,' and a lot of drivers who are really experienced crashed and had a hard time."

As sports like snowboarding and BMX became more mainstream, there seemed to be push inside sliding circles to make the three sports more extreme. The track built for the 2006 Turin Games produced higher speeds — and serious crashes — and Vancouver officials raised the bar further.

"There was kind of an arms race, a speed race," said Todd Hays, a 2002 bobsled silver medalist. "Every track wanted to have the fastest speeds and the scariest track. They all wanted just a little bit of a fear factor involved. Unfortunately, it got out of control and people got hurt.

"But the IOC jumped in immediately and put the brakes on all that, said we're going to reduce speeds and increase safety. And Sochi actually responded incredibly well. They have a great track. It's actually very fast but it's incredibly technical so there's a lot of driving elements, a lot of skill to it. It's safe to get down but very hard to go fast, and so I think it's really going to show off the top drivers."

Many sliding competitors wore black armbands to Vancouver's opening ceremonies in tribute to Kumarishtavili. While there are no formal plans to remember him at these games, and his family declined an invitation to attend, he hasn't been forgotten.

Earlier this week, Canada's luge team, unintentionally pulled into the controversy surrounding the tragedy on their home ice, walked the length of Sochi's track. The group inspected every curve and corner, touching the pristine surface while making mental notes before their runs.

As they took the tour, there was no mention of the past or Kumaritashvili.

Reflection was done in silence.

"We all move forward with Nodar in our minds and heart and with respect to his memory," said Alex Gough, a medal contender in women's luge. "Four years later, it's really time to move on from that and focus on what is in front of us. It's about these games and the future and where the sport is going."