Obama’s Castro condolences in line with tradition

Cuban-American lawmakers have denounced President Obama’s tepid statement about the death of Fidel Castro, accusing the White House of whitewashing decades of human rights abuses. But Obama’s reaction fits a modern tradition of American presidents playing down, or entirely ignoring, those sorts of criticisms when responding to a foreign leader’s passing.

Obama’s statement alluded to “the countless ways in which Fidel Castro altered the course of individual lives, families, and of the Cuban nation,” and predicted that “history will record and judge the enormous impact of this singular figure on the people and world around him.” There were no references to longstanding U.S. condemnations of Havana’s record on political, economic and religious rights.

This isn’t uncommon.

When Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin died in March 1953, the United States lost a vital World War II ally turned ruthless Cold War enemy. President Dwight Eisenhower’s remarkably terse official condolence statement made no mention of life behind the Iron Curtain or of USSR expansionism.

“The Government of the United States tenders its official condolences to the Government of the U.S.S.R. on the death of Generalissimo Joseph Stalin, Prime Minister of the Soviet Union,” it said.

(Ike delivered a fuller appreciation for what Stalin’s death meant in a famous speech to newspaper editors on April 16, 1953 — indicting the Soviets but also challenging Moscow’s new leaders to help defuse Cold War tensions and bemoaning military spending. The remarks were titled “The Chance for Peace.”)

When Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh died on Sept. 2, 1969, President Richard Nixon did not dwell on the tens of thousands of Americans killed by Communist forces in the Vietnam War. Instead, at a press conference on Sept. 26, he mused that the revolutionary leader’s death might lead down a new path in bilateral relations.

“Looking to the future, as new leaders emerge, as they look at the consequences of past policy and the prospects for future policy, and as long as the United States holds to its course, I think the prospects for a possible change are there,” Nixon told reporters. “I am not predicting it. I am not trying to raise false hopes. I am only suggesting that since there is new leadership, we can expect perhaps some reevaluation of policy.”

When Mao Zedong died in September 1976, President Gerald Ford did not note the tens of millions who suffered under the Chinese leader’s rule, either in deadly famines resulting from his economic policies or in “Cultural Revolution” purges.

“Chairman Mao was a giant figure in modern Chinese history,” Ford said, in language remarkably similar to Obama’s statement on Castro. “He was a leader whose actions profoundly affected the development of his own country. His influence on history will extend far beyond the borders of China.”

Ford noted that Mao and Nixon had worked “to end a generation of hostility and to launch a new and more positive era in relations between our two countries” and declared, “I am confident that the trend of improved relations between the People’s Republic of China and the United States, which Chairman Mao helped to create, will continue to contribute to world peace and stability.”

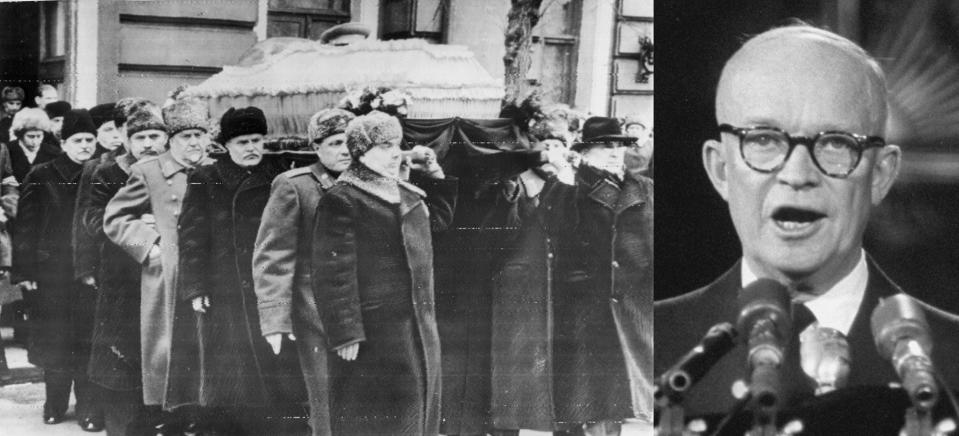

Ronald Reagan’s uncompromising criticisms of the Soviet Union are legendary. But there’s no reference to the “Evil Empire” in the White House’s November 1982 statement on the death of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev.

“The President is expressing his personal condolences to Mr. Kuznetsov, First Deputy Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the U.S.S.R., on the death of Soviet President Brezhnev. A high-level delegation will represent the United States at the memorial ceremonies in Moscow,” the statement said.

“As leader of the Soviet Union for nearly two decades, President Brezhnev was one of the world’s most important figures. President Brezhnev played a very significant role in the shaping of U.S.-Soviet relations during his Presidency,” it continued.

“President Reagan is conveying to the Soviet Government the strong desire of the United States to continue to work for an improved relationship with the Soviet Union and to maintain an active dialog between our societies on all important issues. The President looks forward to a constructive relationship with the new leadership of the Soviet Union.”

(Reagan’s statement on the death of Soviet Premier Yuri Andropov was similarly diplomatic.)

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini led Iran’s 1979 revolution, supported the Iranian hostage takers at the U.S. embassy in Tehran and frequently labeled the United States “the Great Satan.”

When he died, in June 1989, President George Bush issued a terse statement at least implicitly criticizing Iran, but in relatively muted terms.

“The official Iranian news agency has confirmed the death of the Ayatollah Khomeini. With his passing, we hope Iran will now move toward assuming a responsible role in the international community,” the White House said.

President George W. Bush’s November 2004 statement on the death of Yasser Arafat makes no mention of what was, by then, his deep mistrust for the Palestinian leader.

“The death of Yasser Arafat is a significant moment in Palestinian history,” Bush said. “We express our condolences to the Palestinian people. For the Palestinian people, we hope that the future will bring peace and the fulfillment of their aspirations for an independent, democratic Palestine that is at peace with its neighbors. During the period of transition that is ahead, we urge all in the region and throughout the world to join in helping make progress toward these goals and toward the ultimate goal of peace.”

Obama’s diplomatic statement about Castro set aside longstanding criticisms of the Cuban leader’s record — including by Obama’s own State Department in its annual human rights reports. That may be well worth criticizing, but it’s not unusual. It also bears noting that the response to his statement stems as much from American politics as Cuban affairs — from the vocal Cuban-American constituency that also rejects the president’s efforts to end one of the Cold War’s final disputes.