Obama visits slave site of disputed importance

GOREE ISLAND, Senegal (AP) — Soon after being released from his 27-year incarceration in South Africa, apartheid icon Nelson Mandela made a pilgrimage to this small island off the Senegalese coast.

He came to pay homage to a salmon-colored house which locals claim was used to hold slaves before herding them onto ships bound for America. When the curator showed him a hole underneath the staircase used to punish disobedient slaves, who were left to die in the crawlspace, Mandela himself climbed in.

He re-emerged, his face wet with tears, says Eloi Coly, the museum's chief conservator, who recalled the impact the experience had on Mandela, just hours before showing the building to President Barack Obama, who visited the structure on Thursday. For Coly, Mandela's emotional response underscores the role that this building, known as the House of Slaves, has had on crystalizing the stain that slavery left on humanity.

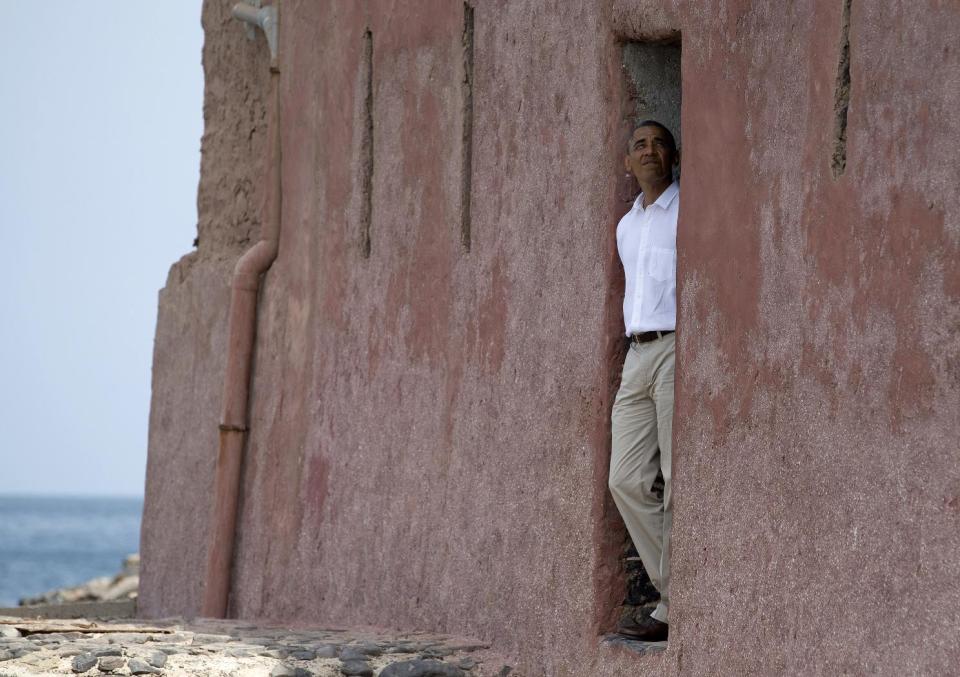

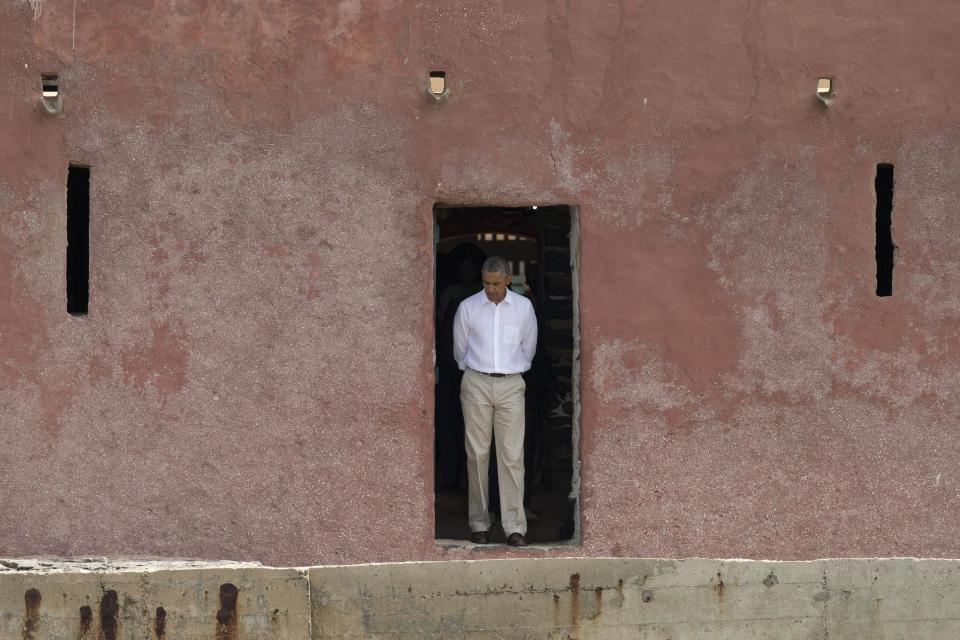

The hole is one of the features Coly planned to show Obama. The other is the door facing the open water, the so-called Door of No Return through which the shackled men, women and children left Africa, inching across a plank to the hull of a waiting ship. Like with previous tour groups, the curator planned to ask Obama to stand before the open door and contemplate the view, the slaves' last glimpse of Africa, he claims.

The problem though is that historians say the door faced the ocean so that the inhabitants of the house could chuck their garbage into the water, the preferred means of waste disposal in preindustrial Senegal. No slaves ever boarded a ship through it, they say, because no vessel could have sailed through the rocky shoal that surrounds that edge of the island.

And while the house may have housed slaves, they were likely those belonging to the family who lived there, rather than slaves intended for the trans-Atlantic passage, according to numerous publications as well as three historians of the slave trade interviewed by The Associated Press.

Even though historians have debunked the memorial, calling it a local invention, and despite reams of scholarly articles, treatises and books discussing its dubious historical role, the pink building has become the de facto emblem of slavery. It's the place where world leaders go to acknowledge this dark chapter and in addition to Obama, the museum has hosted former Presidents Bill Clinton and George Bush and Pope John Paul II. Its guestbook is bursting with the emotional messages from African-Americans who made their own pilgrimage here in an effort to make peace with their ancestors' roots.

"There are literally no historians who believe the Slave House is what they're claiming it to be, or that believe Goree was statistically significant in terms of the slave trade," says historian Ralph Austen, a professor emeritus at the University of Chicago who is the author of several articles on the issue. "The debate for us is how loudly should we denounce it?"

From 1501 to 1866, an estimated 12 million slaves from Africa were sent to North America, according to a database created by scholars using shipping records and plantation registers. Of these, only 33,000 came from Goree Island, an insignificant portion of the overall total, the database shows.

Yet the plaques which grace the stone walls of the Slave House speak of the "millions" of slaves that passed through its halls.

In the 1990s, Philip Curtin, an emeritus professor of history at Johns Hopkins University and the author of two dozen books on the Atlantic slave trade, became one of the first scholars to question the authenticity of the Slave House. In a discussion on an online forum for historians, he said he believed the "hoax" was perpetrated by the charismatic Joseph Ndiaye, who preceded Coly as the museum's curator, and who ushered generations of visitors through the house, recounting the alleged horrors perpetrated there with theatrical pomp. Ndiaye initially claimed that 20 million had passed through the house, upping it to 40 million by the time Curtin visited in 1992, four times the total figure of slaves exported from Africa overall.

"A lot of people have been taken in by the Goree scam," Curtin wrote. "Though Goree is a picturesque place, it was marginal to the slave trade."

The debate over the house's place in history has become emotionally charged and politically treacherous in Senegal, due to the high-profile role the museum plays in attracting tourists to the island, including celebrity visitors like Obama.

On the day before the president's planned tour, Coly, who was Ndiaye's assistant up until the curator's death in 2009, fielded calls from journalists, proudly retelling the anecdote regarding Mandela's emotional visit. In a glassed-in cabinet, he keeps the yellowing picture of Mandela, his expression drawn, even dark, after visiting the house. Next to it are portraits of Bill, Hillary and Chelsea Clinton, their faces pained as they are shown part of the exhibit. And there are framed certificates from UNESCO, which to the dismay of historians added Goree to its list of World Heritage Sites, claiming on its website that "from the 15th to the 19th century, it was the largest slave-trading center on the African coast." Austen and other historians say the listing was political, pointing out that Goree was added in the 1970s, when UNESCO was led by Amadou Mahtar Mbow, a Senegalese national.

Coly, the curator, reacted violently to the suggestion that the house's history may be trumped up, saying those who question it are akin to Holocaust deniers. "There are people who deny that there were concentration camps," he said. "What it shows is a lack of respect for blacks, for the memory of our people."

Ana Lucia Araujo, a history professor at Howard University whose work deals with the history and memory of the Atlantic slave trade, said that historians have never been able to confirm the claims made by the museum's curator. The very real need for a place where slavery can be remembered, she says, has overridden the objections of scholars.

"We have a number of tourists from the United States that go to Goree, because we have no place here to commemorate the Atlantic slave trade," she said. "But that does not make the site a real historical site. It's a site of memory. But it's not a real place from where real people left in the numbers they say."

The irony is that there are real places throughout Africa's Atlantic Coast from where tens of thousands, even millions, of slaves left. Unlike postcard-ready Goree Island, which still has its aging 17th and 18th century architecture, there isn't much to see at the slave depots that played a critical role. "One of them is the port of Luanda in Angola, where the real majority of Africans left — nobody goes there," she said. "If there was an Auschwitz in Africa it was not on Goree. It was in Luanda."

While much of the criticism has come from historians abroad, Senegal's scholars are among the critics, even though they have faced a harsh backlash at home. Among them is a quiet man who, until recently, ran a museum on the other end of the island, about a 15-minute walk from the Slave House.

Abdoulaye Camara, the former curator of the Goree Island Historical Museum, answers the question about the Slave House by asking visitors to head to Exhibition Room No. 1, adorned with historical maps of Goree Island. One of them is from 1775, just before the Slave House was built. "Look at this map and draw your own conclusion," he says.

The map shows that at the time, the edge of the island on which the Slave House was built was surrounded not just by a natural barrier of rocks, which appear as a scribbled band, but also by a rampart, which would have blocked all access for a ship trying to approach the Door of No Return.

"If you contest the Slave House, they start throwing rocks at you. It's not a question of negating our history. ... But we need to understand that this is a symbol. It's not based on fact," he said.

That point was likely lost on Obama, who arrived Thursday with his wife and daughter. He peered out of the Door of No Return. Alone for a brief moment inside the doorway, he stared out across the water, as the waves crashing on the very rocks that would have prevented a ship from docking could be heard.

When he spoke to reporters waiting for him outside, he said visiting the site was a "very powerful moment," which has allowed him to "fully appreciate the magnitude of the slave trade."

___

Associated Press writer Julie Pace contributed to this report from Goree Island, Senegal.