Chance encounter at Ground Zero on 9/11 helps retired NYPD cop to finally get medical help

He was a cop on the corner.

I was a journalist looking for someone to talk to — anyone.

It was early afternoon on Sept. 11, 2001, in lower Manhattan, a few hundred yards from the smoking rubble of the worst terrorist attack in American history — a place that came to be known as Ground Zero.

The neighborhood seemed deserted.

Except for this police officer.

Why we connected then — and what that connection means today — is one of those tales that reveals how some of life's most significant events often begin as mere chance encounters.

For some of us, maybe that accidental meeting in first grade led to a lifelong friendship. Maybe it was a teacher you trusted in college that you still turn to for advice. Or a boss who inspired you — and still does. Or that stunning woman you met on the elevator that you eventually married.

This chance encounter between the cop and me begins on Sept. 11, 2001 — that most confusing of days.

That morning, with my car radio barking news of a massive terrorist attack, I drove frantically through the backstreets of Bergen and Hudson counties to finally reach the Jersey City waterfront at Exchange Place. Across the churning waters of the Hudson River, the twin towers of the World Trade Center had just collapsed after Islamist radicals crashed hijacked commercial jetliners into each of them. Brown-gray smoke blotted what otherwise seemed a perfect azure sky.

Instinctively, I knew I needed to cross the river. But how?

I spotted a tugboat that was about to disembark with a squad of Jersey City police officers and Jesuit priests from the nearby St. Peter’s Preparatory School. The officers wanted to cross the Hudson to just lend a hand at what they figured might be the world’s biggest crime scene. The priests told me they were going to bless dead bodies.

I jumped on the boat.

We crossed the Hudson in silence.

After the tug docked near Canal Street, I walked southward, alone on West Street toward the smoke and rubble of those once-gleaming twin towers that often glowed like orange popsicles in the winter’s sunsets.

I wondered: Was this the start of another war — my generation’s Pearl Harbor? Who knew?

Besides wanting to write a column that tried to answer those questions and convey some measure of meaning of this day, my editors also wanted me to collect comments from ordinary people for a news story.

I didn’t have my laptop. But it did not matter. There was no internet service. Cell towers had been disabled in the attack. Somehow I had to dictate all this by phone back by 5 p.m. to a bustling newsroom in Hackensack, New Jersey. Think here of that old newspaper movie in which a reporter calls, "Hey, get me rewrite."

But first, I needed to talk to people. Witnesses. Anyone who could offer an observation.

The neighborhood, however, seemed deserted.

Finally, at the corner of Murray and West streets, I spotted a police officer. He was alone and leaning against some sort of barrier.

I crossed West Street and approached the officer, telling him I was a newspaper reporter from New Jersey and asking something dumb like: “What do you think of all this?”

Thankfully he didn’t tell me to get lost. The cop gazed up and down West Street for a second or two, his eyes taking in all the gray dust that covered the street and sidewalks, the cars and fire hydrants — even a nearby basketball court. The scene, he said, reminded him of those photographs of all those ash-covered hills of Washington State after the Mount St. Helens volcano erupted in 1980.

"I've never seen anything like this," he added. "I don't think our grandchildren will see anything like this."

I jotted the comments in a notebook and asked his name.

“Marty Davin,” he said. “NYPD.”

Mike Kelly: If an attack like 9/11 happened again, would America unite? Could we?

'I couldn't remember your name'

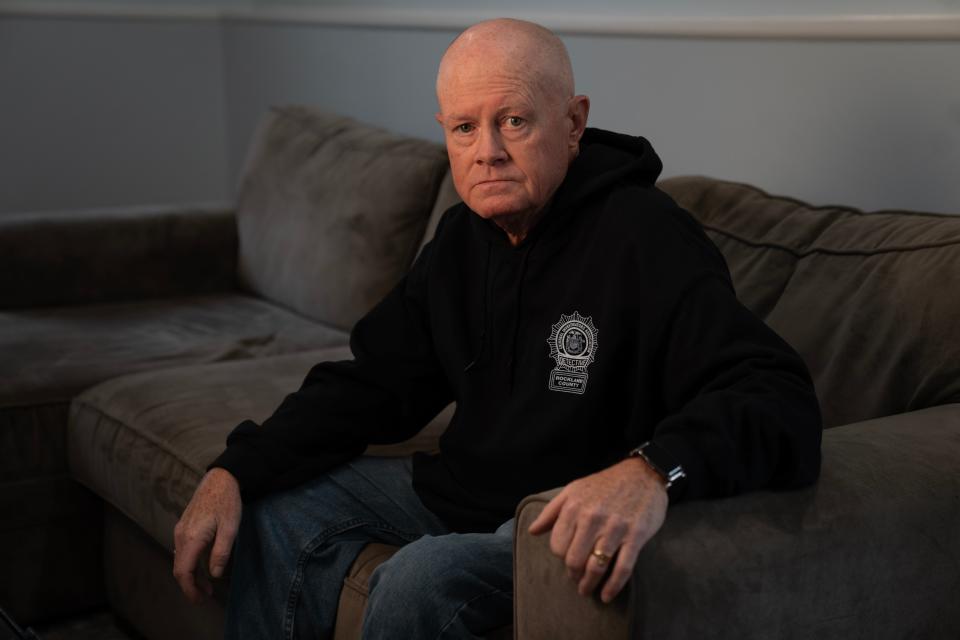

Fast forward to 2024. Marty Davin and I did not see each other again until last month. Davin was now 60 and retired from the NYPD after a 20-year career — 13 years as a detective. He needed help.

What connected the two of us now was a series of diagnoses that Davin had received in the last few years that confirmed he was suffering from 9/11-related health problems. In order to be approved for a variety of pension and health benefits, he needed to prove to his NYPD bosses that he was actually on the scene of the 9/11 attacks. He had no memos, no official reports of what he did on 9/11. But he remembered talking to a journalist.

So he set out to find me.

“I knew I was interviewed by a newspaper reporter and quoted in an article,” he said when we finally talked in April 2024. “But I couldn’t remember your name.”

How Marty Davin and I linked up more than two decades after the 9/11 attacks is another piece of this tale of why chance encounters can be so important.

Davin grew up in Fair Lawn, New Jersey. He graduated from St. Joseph’s Regional High School in Montvale. He worked briefly as a meat cutter at a Paramus ShopRite grocery store and studied at William Paterson University in Wayne and John Jay College in New York City before moving to New York City and joining the New York City Police Department.

He was soon promoted to detective. And as the team of al-Qaida terrorists hijacked four commercial jetliners on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001 — crashing two into the twin towers — Davin had been assigned with other NYPD detectives to a federal Drug Enforcement Administration investigation.

When those planes smashed into the towers and also the Pentagon and a Pennsylvania farm field, Davin was driving to work from his home in Rockland County, New York. As soon as he reached the DEA’s secret base a few dozen blocks from what would become Ground Zero, his commanders told him to ditch his undercover look of jeans and a casual shirt and put on an NYPD blue uniform.

Soon, Davin was standing guard on the corner of Murray and West streets — only a few hundred feet from the trade center rubble. He remembers chasing away a looter. But otherwise, he was alone — except for his encounter with me.

What Davin did not know at the time was that he was face to face — breath to breath, actually — with an invisible enemy of dangerous toxins that spewed from Ground Zero into the air. Years later, Davin's doctors told him that he had been exposed so much to those toxins on 9/11 and during the following weeks that he had developed a series of worrisome health problems. These included respiratory ailments, blood complications and skin cancer as well as sleep apnea and what doctors told him was an increasingly compromised immune system.

It wasn’t unusual for Davin to be diagnosed so many years after being exposed to those toxins. Medical researchers have discovered that the putrid air from Ground Zero and the chemical-laden rubble — along with the pulverized concrete — creeped into the cells and tissues of thousands of people. Like moles that hide for years, those toxins did not sicken everyone right away. Years passed before some victims noticed their health had deteriorated.

That was the problem for Marty Davin.

Even though he retired in 2004, he wasn’t linked to trade center-related health problems until eight years later. And not all of Davin’s health problems emerged at once.

In 2012, respiratory issues were diagnosed. Then blood complications. Then skin cancer. And so on.

Davin now concedes that more could be on the way.

'This is a story that needs to be told'

Such concerns and complications are not all that unusual among the thousands of cops, firefighters and other first responders who rushed to the World Trade Center site on 9/11 — and returned to help search for bodies. The air there smelled of death and bad chemicals. Plenty of first responders — and journalists, like me — remarked about how bad the air smelled. But federal officials — notably former New Jersey Gov. Christine Todd Whitman, who was then the head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — assured everyone in those early months that the air and rubble were not toxic.

What’s emerged during the last two decades is nothing less than a burgeoning health crisis that may eventually affect some 400,000 people who lived near the trade center or worked there — or rushed there to help after the towers fell.

So far, some 70,000 people have registered with the federal World Trade Center’s health registry, which is administered by the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. This columnist is one of them. Each year for more than a decade, I’ve scheduled a medical checkup at Mount Sinai, which is compiling a vast trove of health data. Thankfully, I’m healthy.

But others are not so lucky.

Doctors have linked 60 cancers and another two dozen ailments to the toxins that were found in the air and rubble of Ground Zero. And while 2,974 perished in the 9/11 attacks in New York City, at the Pentagon and in that Pennsylvania farm field where the final hijacked plane crashed, nearly 5,000 more have since died of health problems from Ground Zero's toxins. Many are police and firefighters. But the dead also include construction workers, food service volunteers and even a few journalists.

Such gruesome numbers were on Davin’s mind last fall when he set out to find me.

While he had already registered for medical checkups with the Mount Sinai program, he still needed to gain approval from the NYPD’s medical board for additional help.

The board rejected him three times even though he presented plenty of evidence of his worsening health problems related to 9/11 toxins. As Davin learned, the board kept dismissing his claims because his health problems kept changing. Actually, those problems were worsening.

Frustrated, Davin, who is married and the father of two adult daughters, finally turned to Timothy McEnaney, a lawyer based in Port Washington, New York, who has built a practice that specializes in helping 9/11 first responders battle government bureaucracy to receive health benefits.

In several lengthy interviews with The Record and NorthJersey.com, McEnaney confirmed the wide array of health problems that Davin suffered from, along with his painstaking efforts to gain approval for NYPD benefits.

"This is a story that needs to be told — how these cops are being tortured," McEnaney said.

With McEnaney’s help, Davin reapplied to the NYPD medical board a fourth time. Last September, the board finally certified that Davin’s health problems were indeed linked to Ground Zero.

But now another problem emerged — the NYPD pension board.

For Davin to receive special 9/11 disability benefits, he had to gain approval from the police pension board. And in talking to other officers, Davin realized he had a problem: How could he prove that he was actually near Ground Zero on 9/11?

To qualify for the special pension, Davin had to show he was near the trade center rubble on Sept. 11, 2001 or on the next day — or had spent another 40 hours at Ground Zero in subsequent months.

Davin knew the truth. Not only had he rushed to the trade center on Sept. 11, 2001 and on the following day; he kept returning. But NYPD did not have detailed records of how many officers made their way to Ground Zero during the attacks. Many cops were so busy that they didn’t even bother to fill out reports or make notes in their memo books.

The NYPD, meanwhile, also worried about fraud — perhaps overly so. Suppose, for example, that the lung cancer a cop had developed a few years after the 9/11 attacks was actually linked to a longtime smoking habit and not breathing Ground Zero’s toxins?

Such concerns were understandable. But in Davin's case, they were completely unfair.

More Mike Kelly: Exclusive: New FBI documents link Saudi spy in California to 9/11 attacks

A 'guy with an Irish name'

It was now October 2023. He had to find a way to prove he was at Ground Zero on Sept. 11, 2001. But how?

That’s when he remembered being interviewed briefly by what he thought was “some newspaper reporter from New Jersey” — a “guy with an Irish name.”

Davin was now living in Florida with his wife. He remembered reading his quote in a news article in which he compared the ash-covered streets of lower Manhattan to the photographs he had seen from the eruption of Mount St. Helens years ago. He even remembers buying The Record the next day at a convenience store.

But he couldn’t find the newspaper now.

“I decided to become a detective again,” he told me. “I needed something solid.”

His attorney, Tim McEnaney, was skeptical. "I said, 'good luck,'" McEnaney recalls telling Davin. "What are the odds that the reporter you spoke with is still working? Or still reachable?"

Davin searched Google. But The Record’s articles from 2001 had been erased. Next, he purchased a subscription to The Record’s computerized archives.

He found the article that mentioned him. It was printed on Page 3 of the Sept. 12, 2001 Record – the edition that carried dozens of stories about the 9/11 attacks and included the soon-to-be-iconic photograph by The Record’s Thomas Franklin of three New York City firefighters raising a U.S. flag over the trade center’s rubble.

The article mentioning Davin was titled “Witnesses Face Reality of Terror.” It seemed endless — more than 5,200 words long, with 45 observations and vignettes by Davin and others across New York and New Jersey. Worse, the article’s credit line showed that it had been assembled by one writer, with contributions by 28 other Record staffers who ranged from reporters who covered food, music and transit issues to high school sports and wrote editorials. The main writer, who crafted the heartfelt narrative, spent most of his time covering the New York Knicks professional basketball team. In short, it was one of those newsroom days when everyone pitched in.

Davin looked over the names of the contributors — all listed in alphabetical order — and started running Google searches to find contact information. It turns out many had left The Record. Some had moved away. Some found other jobs. Some were retired. A few had since died.

Davin then remembered that the reporter who interviewed him had an “Irish sounding name.”

He tried the first Irish surname on the list — Michael Casey. No luck.

Then, Davin reached out to Scott Fallon, who was still writing for The Record as its environmental and health reporter.

Fallon told Davin he was probably looking for me. Meanwhile, Fallon sent me an email entitled: “9/11 cop” and mentioned how “a retired NYPD officer named Marty Davin” was “trying to prove that he was near Ground Zero on 9/11 to be part of the health fund.” Fallon knew I had been at Ground Zero on Sept. 11, 2001. Fallon included Davin's phone number in his email. Could I help?

I dived into The Record’s computerized archives and found the lengthy news story I contributed to. Yep, that was the police officer I met at the corner of Murray and West streets.

I dialed Davin’s phone number.

Davin quickly explained his dilemma. The World Trade Center’s health monitoring program was treating him for 9/11-related illnesses. But the NYPD’s pension board would not approve special 9/11-related benefits unless Davin could prove he was near Ground Zero on 9/11 or the following day — or at least 40 hours during subsequent months. Davin felt he was being unfairly scrutinized by his own police department.

Could I verify to the NYPD that I spoke to Davin on Sept. 11, 2001?

Of course, I could. And weeks later, I sent a two-page letter to the NYPD pension board, explaining that Davin was on duty near Ground Zero on Sept. 11, 2001.

The pension board dragged its bureaucratic feet for nearly five more months. Finally, on April 10, the board concluded what should have been obvious years before — that Marty Davin actually ran toward danger on 9/11 and was now paying for that courage with a myriad of health problems.

The pension board classified Davin for full 9/11 pension benefits.

Weeks later, when we finally met over lunch in a Rockland County, New York, restaurant, Davin told me that his medical checkups with the World Trade Center health monitoring system were becoming more frequent. As we ate, his phone buzzed with a call from one of his doctors, setting up an appointment.

Despite such stress, Davin told me he felt relieved that he had managed to pass the scrutiny by the pension board.

And it was all because of a chance encounter on a street corner.

"If my name wasn’t printed in your newspaper," he said, "I would probably still be fighting with the board."

Mike Kelly is an award-winning columnist for NorthJersey.com, part of the USA TODAY Network, as well as the author of three critically acclaimed nonfiction books and a podcast and documentary film producer. To get unlimited access to his insightful thoughts on how we live life in the Northeast, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kellym@northjersey.com

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: 9/11 encounter with reporter gets retired NYPD cop medical help now