NSC head McMaster knows what it will take to defeat ISIS. But will Trump listen?

NEAR TAL AFAR — On the rolling hills of the battlefield near Tal Afar in northern Iraq, fighters belonging to the armed brigades known as the Popular Mobilization Forces [PMF], made up of mostly Shiite tribal members, hustle to and from a front-line base confronting forces of the Islamic State.

Tal Afar is still largely under the control of ISIS. The PMF has captured the city’s airport, but its forces remain mostly on the outskirts of the city, three to five miles from the center.

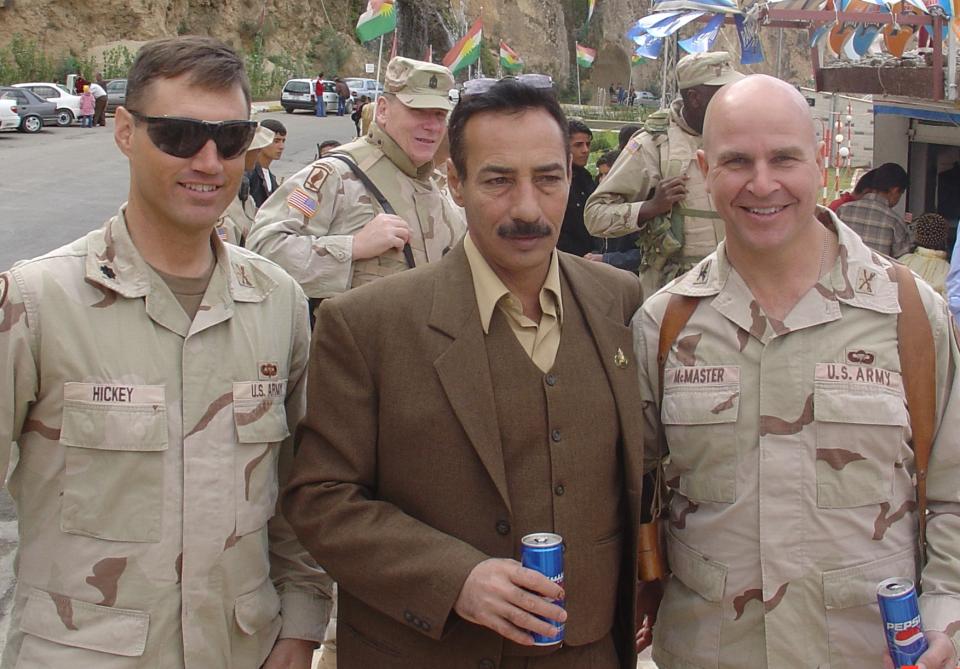

The city was once held up as an example of tribal unity between Shiite and Sunni Muslims after it was liberated from al-Qaida by American troops commanded by then Army Col. H.R. McMaster.

Last month President Trump nominated McMaster, now a lieutenant general, as his national security adviser, a pick that was widely praised by both Republicans and Democrats. McMaster’s experience in Iraq goes back to 1991, when as a captain in the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment he commanded a tank unit that defeated a much larger Republican Guard force, a battle for which he was awarded a Silver Star. His doctoral thesis became a popular book, Dereliction of Duty, which argued that American military commanders during the Vietnam War failed to challenge their superiors on their flawed strategy.

His approach to military operations earned him respect when he ousted al-Qaida insurgents in 2005 in Tal Afar by attempting to forge alliances among Iraqi tribal leaders and religious factions.

Now as another war rages in northern Iraq over Tal Afar and Mosul, McMaster’s reputation and experience may be useful in helping Trump formulate a strategy.

But Trump has shown little interest in the ongoing battle in Iraq, instead focusing on the defeat of what he has called “radical Islamic terrorism,” a phrase McMaster rejects. Trump’s campaign rhetoric called for harsh measures, including torture for prisoners, and he raised the possibility of taking revenge on fighters’ families, which would alienate the very people McMaster worked so hard to win over.

This war, with new soldiers fighting an even fiercer enemy that uses civilians as human shields and shoots refugees when they attempt to flee, could be a recipe for disaster even if ISIS is defeated; the American forces and the Iraqi government may not be able to maintain tribal and religious unity in the aftermath.

—-

On the Tal Afar front lines, most in the PMF, also known in Arabic as Hashd al-Shaabi, for now are still taking orders from Baghdad.

Sheikh Maitham Zain, one of the commanders of a PMF brigade, spoke with Yahoo News. He said, “The most difficult thing we are facing is the human crisis here. Mortars hit us. There’s a house [ISIS uses] where there are two floors. On the second floor, there are ISIS fighters, underneath [civilians]. We are fighting for families.”

Zain went on to explain why he thinks the battle for Tal Afar is important. “The most important leaders from ISIS are from Tal Afar, and it’s made the battle for Tal Afar more difficult.”

But one of Zain’s own fighters, a 16-year-old named Meysar, is also from Tal Afar. He is of Turkmen ethnicity, a majority Sunni group. He says he is fighting for his family’s land. “After ISIS took over Tal Afar, we ran away to escape, now we want to take it back.”

His family is safely in another city, but he believes they’ll be able to go home after ISIS is kicked out of Tal Afar.

While Meysar is too young to remember McMaster, he says he does remember living his whole life with war around him. “I’ve been injured,” he said, during battles in Turkmen communities in Iraq. And while he didn’t say how he’d been injured, it helped make him stronger: “Now I’m a good [fighter].”

Meysar was shy, but it was evident he was happy to be allowed to fight with the PMF. For him, it’s revenge against ISIS.

The PMF comprises around 40 units, under an umbrella created by the Iraqi government to unite militias against ISIS. Most of the Shiite brigades receive some support from Iran, while Turkey supports the outnumbered Turkmen and Sunni brigades. But there is rivalry. Some of the Shiite militias have been accused by human rights groups of mistreating Sunni civilians.

—-

In 2005, when McMaster entered Tal Afar, one of his main strategies for defeating al-Qaida insurgents was to integrate his soldiers into the local culture and society, and to create trust between Shiite and Sunni Muslim communities.

He even trained his men, at a base in Colorado with simulated situations and role playing in dealing with Arab culture, language and customs, and in interacting with religiously minded tribes. His tactics were considered successful.

Iraqi Gen. Najim al-Jabouri, who now oversees all operations for Nineveh province in northern Iraq and the Mosul offensive, was chief of police in Tal Afar before becoming mayor in 2005.

In an interview with Yahoo News he explained that “the problem in Tal Afar, the [former] chief of police was from the Shia {Shiite} side and the mayor was from the Sunni side and they created problems. The mayor, at that time, worked with the terrorists.”

“Al–Qaida controlled most of the city,” he said, and “life was difficult.” Tel Afar often looked “like a ghost [town], there were no birds, no life.”

But he takes pride in his relationship with the American forces. “I was a good adviser. I told them, ‘We need to win the people.’” Together they were able to rid the city of al-Qaida by the end of 2005. He believes the U.S. forces were key to helping create the “golden years” for Tal Afar, which lasted until 2007.

Jabouri said, “In the beginning we cleaned [the city of al-Qaida]. after that, we held the city very strong. After that, we had to build, give the people jobs. And step by step, the relationship between the Sunni and Shia and the American forces got better.”

The concept of “clear, hold and build” that Jabouri alluded to is a counterinsurgency strategy applied by Gen. David Petraeus in Afghanistan and Iraq. McMaster used this approach to rebuild civil society in Tal Afar.

But even so, intermittent attacks continued in the city from 2007 on — and American soldiers were gone by 2011, against Jabouri’s advice. He said McMaster agreed with him, but it seemed the U.S. government wasn’t interested.

In 2014, ISIS took over Tal Afar.

Jabouri blames weak Iraqi security forces and corruption, which angered the people and reawakened sectarian divisions. Jabouri also believes that for Iraq to have a peaceful future, the Iraqi central government must “learn the lessons” of the past and invest in healing the rifts between the tribes.

—-

But at another front in the battle for Tal Afar, another PMF commander, who calls himself Abbas, sits in a safe house near the front lines, and in a dimly lit room welcomed Yahoo News.

Abbas is strong in his Muslim faith and he attributes his mission to fight against ISIS and freeing civilians as “God’s orders.” For him, outside forces have perpetuated the disunity and conflict in his country.

But he’s not from Tal Afar and doesn’t know much about McMaster’s campaign, so he’s skeptical of American involvement. “Considering they are the strongest in the world, they are the ones who invaded [against] Saddam [Hussein] and created chaos in Iraq.”

While he acknowledges that the Americans have upgraded Iraq’s weapons and technology, he is still angry about their 2003 invasion of Iraq and says the U.S. has not paid for the damage. “They didn’t repair [relationships] in Iraq, but they did sow more chaos and blood and bad people.”

He also thinks outside majority Sunni countries, such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia are benefiting from the conflict in Iraq. “There is a fight for an Islamic leader and in that, the Turkish and the Saudis [benefit].”

When dinner was brought to the room, Abbas and his men shared their favorite war stories, joked and laughed. But when the conversation grew more serious, they began talking about their frustration with their rivals, the Kurdish Peshmerga fighters.

Last year, heavy clashes between Shiite militias and Peshmerga in an eastern province of Iraq left nearly 50 dead, most from Hashd al-Shaabi forces. Many in the PMF still carry wounds from the battle.

But Jabouri puts much of the blame on the Iraqi central government and the country’s Constitution. He believes it is problematic because it identifies the people by their religious and ethnic groups, Shiite, Sunni, Turkmen and Kurd, rather than “Iraqis,” as a whole. This, he said is “part of the disaster in Iraq.”

With tribal lines drawn, McMaster’s hopes for national unity seem distant. Gen. Jabouri however, has hope. He considers McMaster his friend; they’ve stayed in close touch over the years and he believes McMaster can influence Trump’s decisions over Iraq, both militarily and in repairing his beloved country.

—–

Back at the front-line base, near Badoush, PMF fighters loaded cannons aimed at ISIS forces across the open fields. The tube-like shooters were set up in a grassy yard outside a small house. When fighters hear ISIS shoot, they shoot back.

In between the loud pops of cannon rounds, fighters laugh and pose for photos. They don’t have common military uniforms: Some wear used U.S. or Russian camouflage, some mix and match with their own clothes, others add scarves on their heads, and some even walk around without proper shoes or protective gear. For now, these men don’t care much about the American involvement. PMF fighters don’t receive air or ground support from coalition forces, which are more heavily involved in Mosul.

“We don’t have any connection with the coalition,“ Zain said, “Our weapons and support are from the Iraqi Defense Ministry.”

They take pride in pushing ISIS back on their own, but Zain also emphasized he would like to see a unified Iraq overcome religious differences. “We as fighters here believe we are fighting on behalf of the world and behalf of [the U.S.],” he said, “Human kindness is not based on the interest of parties; we look at people with one [set] of eyes, equally.”

Zain pointed out that his unit helped host a medical clinic with a makeshift emergency room, treating wounded soldiers and civilians alike.

Fighters and medical staff rushed to the examination room for initial treatment and then helped carry a stretcher to a Red Crescent ambulance. PMF soldiers recited a common Shiite prayer to bless the injured, “Oh God, praise and peace be upon Muhammed and his families,” they chanted. For this PMF brigade, the mission was humanitarian.

—-

Based on his rhetoric, Trump sees the American mission here as less about stabilizing or unifying Iraq with humanitarian assistance and more about rooting out an existential military threat to the U.S. During the presidential campaign, Trump said he would have a plan for defeating ISIS in the first 30 days of his presidency, but so far Trump’s administration has yet to roll one out.

McMaster may have his work cut out for him in the weeks ahead. Political analyst and Brookings Institution fellow Jeremy Shapiro says, “These two are set up for conflict and failure. McMaster is so antithetically opposed to the approach to Islam and the war on ISIS that Trump has proposed that I can’t see him accepting it.”

Shapiro believes that although Trump praises military leadership, he really isn’t focused on details of Middle East conflicts, nor is he very interested. For Trump, he said, the mission is just about “killing terrorists” and “going home.” He added: “If you allow the generals to deal with it, they’ll suck resources in forever.”

The American people, Shapiro fears, don’t have “the national will” to occupy Iraq and sustain the casualties necessary to reconstruct a country whose internal rivalries they barely begin to understand. McMaster does understand, but whether his vision and advice will prevail in the treacherous climate of the Trump administration remains to be seen.

Once ISIS is expelled from Iraq and tribal militias no longer have a common enemy — or the backing of coalition forces — the old rivalries may resurface, and once again create an opening for another extreme and armed insurgency.

_____

Ash Gallagher is a journalist covering the Middle East for Yahoo News.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Sean Spicer spars with White House press corps over wiretapping

How an L.A. House district’s special election could mark a new direction for Dems

Health care fight raises concerns about Paul Ryan’s leadership

Cuts to poverty programs are ‘as compassionate as you can get,’ Trump budget chief says

Photos: Man killed after trying to grab soldier’s gun at Paris airport