Now That We've Seen a Black Hole, Here's What Future Photos Could Look Like

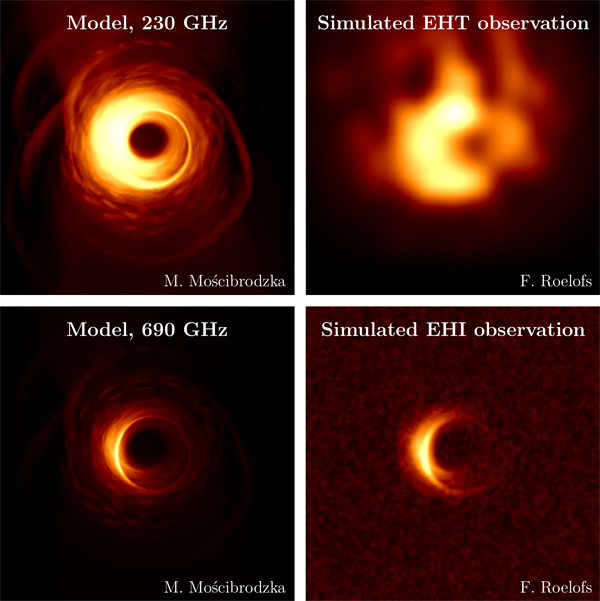

The world's first picture of a black hole captured imaginations around the globe. Now comes the next challenge for scientists: taking better, sharper photos, in hopes that they will be able to test Einstein's Theory of General Relativity. To get there, they want two or three satellites orbiting the planet looking for black holes.

The scientists are calling their creation the Event Horizon Imager (EHI).

"There are lots of advantages to using satellites instead of permanent radio telescopes on Earth, as with the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) [the consortium that captured the first image of a black hole]," says Freek Roelofs, a Ph.D. candidate at Radboud University and the lead author of the article proposing the idea, in a press statement.

"In space, you can make observations at higher radio frequencies, because from Earth these are filtered out by the atmosphere," Roelofs says. "The distances between the telescopes in space are also larger. This allows us to take a big step forward. We would be able to take images with a resolution more than five times what is possible with the EHT."

While the original black hole photos proved, as radio satellites had done years prior, that black holes exist, scientists are eager to dive into the details. Even the smallest unexpected discovery could have cosmic repercussions.

"The fact that the satellites are moving round the Earth makes for considerable advantages," Radio Astronomy Professor Heino Falcke says in the statement. "With them, you can take near perfect images to see the real details of black holes. If small deviations from Einstein's theory occur, we should be able to see them."

The scientists proposing the EHI have five particular black holes in mind, each smaller than the one at the center of the galaxy known as Messier 87, home of the original black hole picture. The EHI system would be able to capture the bigger black holes like M87 or Sagittarius A at the center of the Milky Way, while also looking at smaller black holes.

Of course, it took years of work and collaboration across the globe to capture the first image of a black hole. A second system of picture-taking will likely take a long time as well.

"The simulations look promising from a scientific aspect, but there are difficulties to overcome at a technical level," Roelofs says.

Scientists worked with the European Space Agency (ESA) t0 make sure the idea was possible.

"The concept demands that you must be able to ascertain the position and speed of the satellites very accurately," according to Volodymyr Kudriashov, a researcher at the Radboud Radio Lab who also works at ESA/ESTEC. "But we really believe that the project is feasible."

One of the biggest challenges could be sharing data between the satellites. "With the EHT, hard drives with data are transported to the processing centre by airplane," Kudriashov says. "That's of course not possible in space."

That's why the team is proposing a laser link, with data partially processed on board prior to continued study on the home world. It would be similar to the laser links used to monitor Earth-observing satellites used by the European Data Relay System.

"There are already laser links in space," Kudriashov points out.

Scientists looking to build on the data from the EHT also say a hybrid system might work, with the orbiting telescopes joining the eight powerful telescopes on Earth that worked together for the iconic image.

"Using a hybrid like this could provide the possibility of creating moving images of a black hole, and you might be able to observe even more and also weaker sources," Falcke says.

Source: Radboud

('You Might Also Like',)