They can now eat a few M&Ms — new peanut allergy treatment is changing kids’ lives

When Jack McKelvey was 4 ½ years old, his life changed dramatically when he ate a chocolate chip cookie that had touched a peanut butter cookie.

He broke out in hives and was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy, one of the most prevalent food allergies in children. “His reaction to the proteins in peanuts is very, very high,” said his mother Louise McKelvey, of Hollywood. He didn’t need to consume any nuts; a severe reaction in Jack could be triggered just by being in the vicinity of a peanut product.

At school, that meant he had to sit at a special “allergy table” in case one of his classmates brought a peanut butter sandwich for lunch. There were no outings to the ball park with peanuts and Crackerjacks when his beloved Red Sox played. His mother had to do a complete wipe-down of all surfaces near his seat when they flew to visit his grandmother in England, and his family never ate out for fear Jack would be exposed to a peanut product at a restaurant.

“He was very aware he was different. There were no cakes, no birthday cupcakes. It was very isolating for him,” said McKelvey.

But Jack’s life, now at 9 years old, has once again changed drastically thanks to a new treatment for food allergies available at Memorial Health’s Joe DiMaggio Children’s Hospital. Called oral immunotherapy, it introduces the patient to very minute quantities of food allergen over time, essentially fooling the immune system and desensitizing it to the allergen.

Only one-third of pediatricians follow peanut allergy protocol, survey says. Here’s why

It allows those with food allergies like Jack’s to tolerate accidental exposure. Some patients eventually can freely eat the food that once caused an allergic reaction.

“Tolerance is the ultimate goal,” said Dr. Hanadys Ale, a specialist in pediatric immunology and allergies at Joe DiMaggio, which has pioneered the treatment in South Florida. “You’re teaching the immune system that it is okay not to react.”

“It’s a phenomenal treatment,” said Vivian Cino, a nurse practitioner who is the immune therapy coordinator at Joe DiMaggio’s clinic. “Oral immunotherapy has been in the works for almost 10 years and now it is finally available.”

Some patients participating in the allergy desensitization program have no desire to eat peanuts, but Cino developed a knack for distraction techniques and made it fun for the young patients.

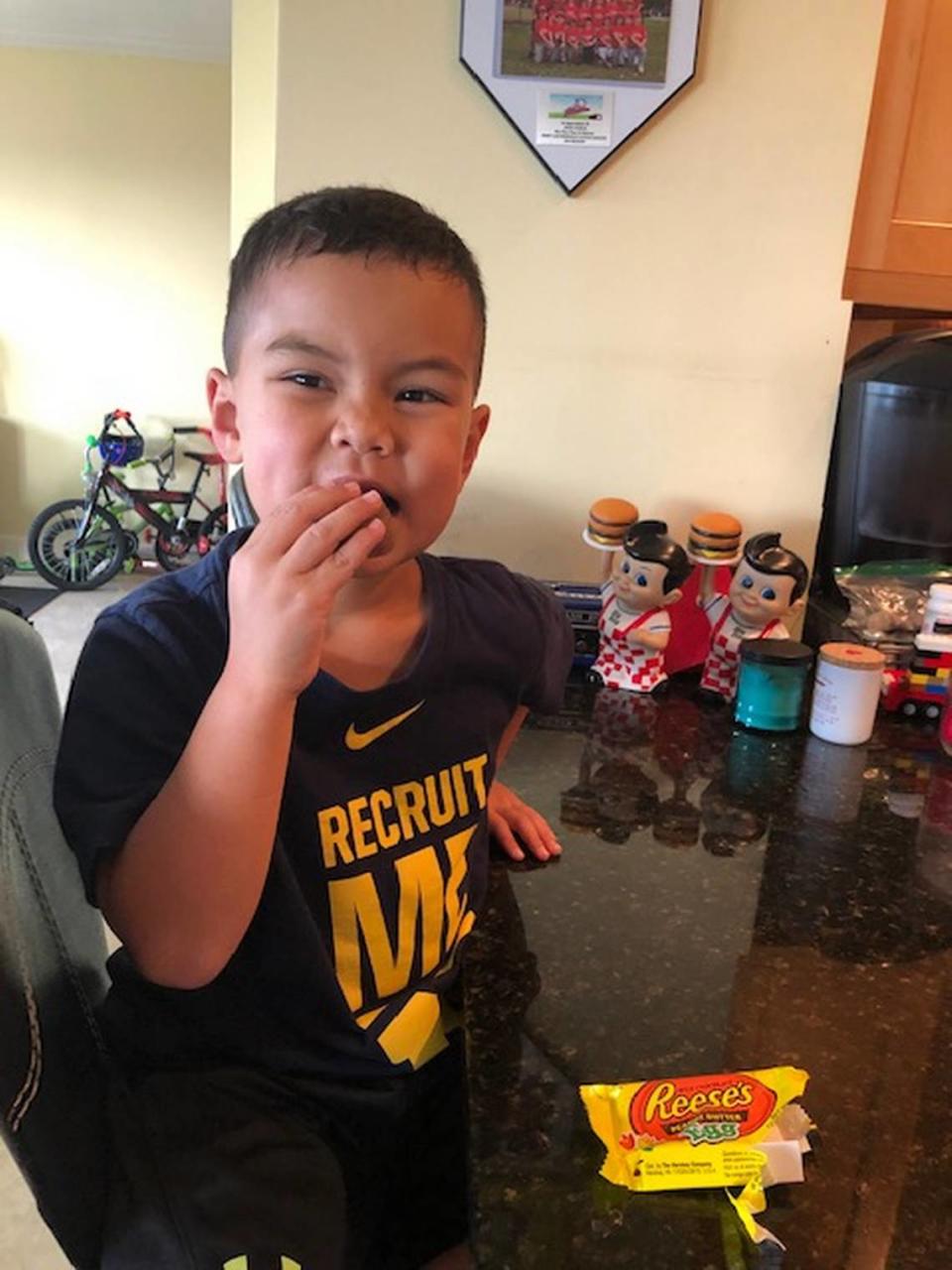

Enzo Martinez, who began participating in the Joe DiMaggio program when he was 4 years old, forgot he was even at the doctor’s office after a few visits and eventually could eat Easter candy containing peanut products.

“You can be allergic to just about any food, but about 90 percent of allergies are caused by the Big Eight,” said Ale. They include cow’s milk, eggs, soy, wheat, peanuts, tree nuts, fish and shellfish with sesame rapidly pushing its way into the top group at No. 9.

For some, food allergies are uncomfortable, causing reactions such as hives, an itching tongue, swelling of the lips and face, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and watery eyes. But they also may cause a sudden and severe allergic reaction called anaphylaxis that results in airway obstruction, shock and may even cause death. The only effective treatment for anaphylaxis is an immediate injection of epinephrine.

Around 32 million people in the United States suffer from various degrees of food allergies and about 5.6 million of them are children. That’s about two students per classroom, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unlike certain environmental allergens, there are no shots for treatment of food allergies.

Some food allergies, such as milk, egg, wheat, and soy, are often easily outgrown. About 75-80 percent of children outgrow their milk allergies, for example, by age 10, said Ale.

But what makes peanut and tree nut allergies so worrisome is that only 20 to 25 percent of children can outgrow them without some form of treatment. Peanut allergies, which affect an estimated 6.1 million people in the United States, also can appear at any age and have increased dramatically in the last two decades, more than tripling between 1997 and 2008. A more recent study found another 21 percent increase since 2010.

There’s a surprising reason for the spike in peanut allergies in children

FDA approves new peanut allergy treatment

Also offering new hope to those who suffer from peanut allergies is Palforzia Allergen Powder, which comes in capsule form and which the FDA approved on Jan. 31. The medical-grade peanut protein, manufactured by Aimmune Therapeutics, works on the same principle as oral immunotherapy with gradually increasing doses over time.

But unlike oral immunotherapy, which can be used to treat various food allergies, Palforzia is only approved for children from 4 to 17 years old with peanut allergies. It is not recommended for patients with uncontrolled asthma. After the initial phases of treatment, a maintenance dose must be taken indefinitely.

Joe DiMaggio can offer Palforzia but hasn’t prescribed it at this point. Instead, it has concentrated on offering oral immunotherapy, which is more economical, as a therapy for all the top food allergens, said Cino.

Even though there hasn’t been much experience with Palforzia, “I’m very hopeful,” said Dr. Vivian Hernandez-Trujillo, director of allergy/immunology at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital. “The studies look very, very promising.” Nicklaus hasn’t started to prescribe Palforzia to its patients yet.

She said she also finds OIT “very promising” for food allergy patients.

Hernandez-Trujillo said she was about to start using Palforzia in her private practice, but the COVID-19 pandemic has delayed its introduction because of the need for in-office visits and careful face-to-face monitoring of patients.

Among those eagerly awaiting its introduction is Hernandez-Trujillo’s 14-year-old daughter, Sophia Whitcomb, who suffers from peanut allergy as does her 10-year-old sister Olivia and her mother, who was diagnosed as an adult.

“I’m actually planning on doing Palforzia soon. I would love it,” Sophia said.

Sophia was initially diagnosed with peanut allergy at age 3 and the diagnosis was confirmed when she was 6. She’s never had a severe reaction and has learned to be careful.

“It’s not that bad. I’m used to it now, but it can be annoying with birthday party cakes and hanging out with friends,” she said. “It gets better. It’s not the end of the world.”

But her mother says “at the beginning, a food allergy diagnosis can be overwhelming. It’s not easy to live with. It really affects quality of life for an entire family.”

That’s why she’s so encouraged by the new treatment options.

There is also ongoing research on a skin patch therapy and sublingual immunotherapy where a food protein dilution is held under the tongue.

Cino said since Joe DiMaggio’s OIT clinic opened in 2018, it has successfully desensitized more than 25 patients with peanut allergies. Only one case wasn’t successful, she said. Currently, two children are being treated for egg allergies, but the bulk of patients suffer from peanut allergies.

In 2019, the OIT clinic saw 50 patients and enrolled nearly 80 percent in the program. Because the treatment requires strict monitoring, the COVID-19 pandemic has taken a toll on the program this year, said Cino

Jack McKelvey completed the program just before the virus rippled through South Florida.

The essence of the OIT program, which takes about four months to complete, is that increasing and very small doses – fractions of milligrams in the beginning – of the allergen are administered. For peanut allergies, peanut powder is mixed with juice and then super diluted and squirted into the mouth.

“No one should react to that first dose and no one ever has. That first dose is almost a placebo,” said Cino.

After the first dose, there is a 20-minute wait to monitor the patient’s reaction and then the dosage is doubled. The goal on the first day is to administer six doses at 20-minute intervals over a four-hour period.

If all goes well, the patient is sent home with 13 syringes to be administered over 13 consecutive days. Then the patient returns to the clinic for another monitoring session to see if there are any concerning reactions. They are then given another 13 doses of the same strength at the clinic. The therapy continues in this fashion until the threshold at which food allergy reactions occur is raised.

As Jack made his biweekly visits to the clinic, his dosages were gradually increased until he could ingest a piece of peanut, then a whole peanut. Now his maintenance dose to keep up his tolerance is four peanut M&Ms or Reese’s Pieces a day, said his mother.

“We are very clear that this is not a snack. This is his medicine. He cannot freely eat peanuts,” she said.

When children enter the program, parents are given two choices: Safe bite, where the goal is to desensitize the child to the point where there won’t have a severe reaction if they accidentally ingest a food allergen, or taking the treatment to where a child can freely eat what was their food nemesis.

“At the end of treatment, some patients can eat a peanut butter sandwich,” said Cino. “It does happen.”

Parents with younger children tend to opt for the second option more often, she said. By the time children with food allergies are older, Cino said many have developed aversions to the food that makes them sick and have no interest in eating it.

One reason Cino said she prefers OIT over Palforzia is that it’s highly manipulative and can be used to treat a variety of food allergies. “We can reduce the doses, spread them out, slow them down,” she said. “Not every child is the same.”

But like Palforzia, OIT isn’t for everyone.

Patients with poorly controlled asthma are not good candidates nor are very young children. The patient must be verbal enough to explain that their lips are tingling or their tummy is hurting after a dose, said Cino. The youngest child treated at the clinic was 3 years old.

Undertaking the program also requires discipline. “I ask is there support, do you have the time, how active is your child’s schedule?” said Cino. “There are many questions to be answered so I can successfully start and carry out the program.”

When a dose is given, for example, a child is supposed to limit physical activity for two hours before and two hours afterward, sometimes making it difficult if a child has many after-school activities or plays sports. Each dose also must be administered 12 hours but not more than 36 hours apart. The child cannot miss a dose and cannot be running a fever.

For Louise McKelvey and her husband, any inconvenience associated with the treatment is small compared with the family’s life now. “OIT has had such a tremendous impact on our family,” she said. “It changed everything.”

Now Jack will be able to go to the ballpark once the pandemic is over. He can share an after-game snack of doughnuts with his baseball teammates without worrying that the treats were cross-contaminated with peanuts during baking.

Right before self-quarantining rules went into effect, the family went on vacation and ate out at a restaurant. For the first time, Jack’s parents told him he could have anything on the menu as long as it didn’t contain peanuts. Since then, Jack has developed a love of sushi.

“The peanut allergy affected Jack. It caused anxiety. Now he’s a totally different child. He’s more carefree, more confident,” said his mother. “I have absolutely no regrets. My hope is his story allows other parents who are where we were a year ago to feel a little more comfortable making the decision we did.”

For some families, avoidance of the food allergen may still be their best option.

In that case, Hernandez-Trujillo says parents and children should make sure they always carry an epinephrine auto-injector and to get to the nearest emergency room immediately if the child experiences a severe reaction.

At a restaurant, she said, it’s important to drill down on how a food is prepared. It isn’t good enough for the restaurant to remove peanuts from a noodle dish, for example, if the same wok is used to prepare the peanut/noodle version.

“The most important thing is we have control. You also should carefully read food labels, every time. Even if the label looks similar to the label on a food that is safely consumed at home, read it. Labels can change,” said Hernandez-Trujillo.

“When your child is diagnosed with a peanut allergy or any allergy, have an action plan on what you will do,” she said. “Information and education really do arm us.”

Mimi Whitefield can be reached at mimiwhitefield@gmail.com or on Twitter @heraldmimi