'Every vote should count': North Dakota ID law threatens Native Americans’ vote in key Senate race

On the tribal reservations, Republicans are accused of trying to suppress a potentially decisive bloc who tend to swing Democratic

As the blanket of morning fog evaporates over the outskirts of Fort Yates, a group of volunteers files inside a nondescript yellow building, decorated with signs that read: Standing Rock Will Vote. Everyone here knows the office. It has stood for decades and is owned by the reservation tribal government. But one thing about it has remained a mystery: its address.

Until recently that would hardly have mattered. Many properties, from government buildings to small homes, have no formal street address. Members of the Lakota Sioux tribe who live on Standing Rock, like the Native Americans on four other reservations in North Dakota, just know where people live. Most residents use PO Boxes to collect their mail. For years, thousands have used their PO Boxes when registering formal identification documents.

Now, with less than two weeks left before the crucial midterm elections, that poses a problem some fear could change the outcome in a pivotal race.

Following a supreme court decision earlier in the month, North Dakota’s voter ID laws will go into effect in November. That means voters will be forced to show ID documents that include a full address before they can cast a ballot. The Republican-backed law has been branded a deliberate attempt to suppress the Native American vote.

“They proposed this legislation and never invited us to be at the table,” said Danielle Ta’Sheena Finn, Standing Rock’s external affairs director. “We were not invited to propose comments or questions or concerns. It was done almost under the rug, which tells you the intent.”

Inside the unnamed yellow building, the small army of volunteers, brought together by a coalition of Native civil rights groups, are determined to fight back. They plan to knock on every single door in the northern side of this vast reservation, which straddles North and South Dakota, and bus people to the single government building issuing new tribal ID cards until all Standing Rock’s population has the documentation required.

It is a mammoth task, in an open place where 3,000 eligible voters live in communities dotted around 1,128 square miles of land.

Alva Cottonwood-Gabe sat in the office, her old tribal ID card in her hand. It expired years ago but the 57-year-old, who lives on $393 a month in food stamps and other government subsistence, simply could not afford to pay $5 to replace it.

“I’ve got four grandchildren to support and I need it to pay for other things in the home,” she said.

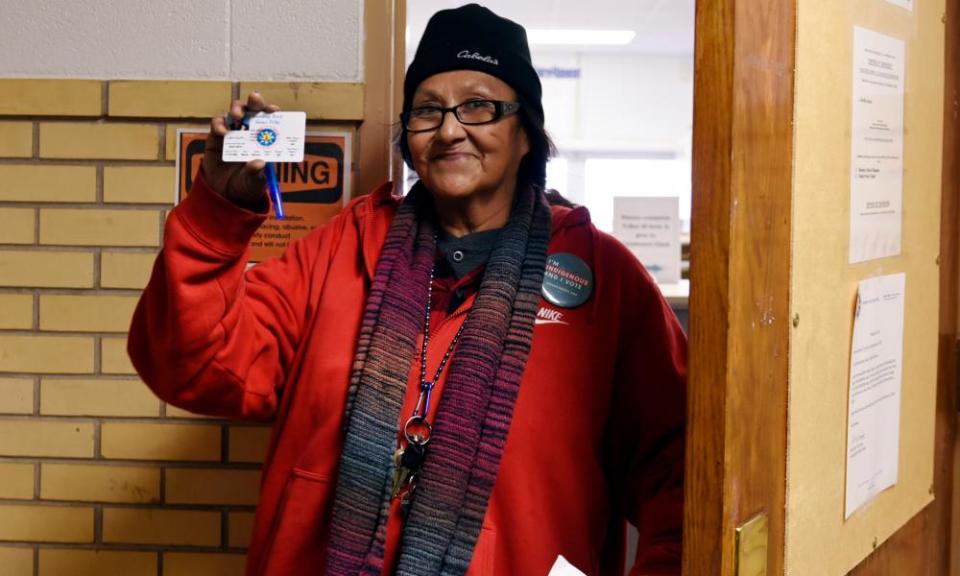

Following the supreme court decision, tribal governments in all of North Dakota’s reservations moved to waive the fee for new documents – soaking up the costs themselves. Cottonwood-Gabe was among the first to be bussed in to collect her new ID, which she brandished above her head, a small marker of victory. It was identical to her previous ID card, bar a single line that noted her address was 568 Sioux Avenue.

The laborious process, which involved three forms and a queue at the federal office, was a reminder to her of what she believed was the new law’s true intent.

“They are trying to suppress our vote because they don’t want to hear what we have to say,” she said. “But voting is so important, not just for me but for my children, my grandchildren, my great-grandchildren.”

A mother of 13 and grandmother of 20, Cottonwood-Gabe is a veteran of the pipeline protests that commanded international attention in 2016. She was Maced three times in clashes with police and left partially deaf in one ear, after authorities used sound cannons.

She has lived in Standing Rock her whole life and voted in every election since 1984. Environmental protection, she said, was the issue that concerned her the most at this year’s election.

The battle for the US Senate seat in North Dakota is among the most crucial races in the midterms. Democratic incumbent Heidi Heitkamp faces Republican congressman Kevin Cramer in an election that could be decided by just a few thousand votes. If Democrats cannot hold the seat, it will be almost impossible for them to take the Senate. Heitkamp, who voted against Donald Trump’s controversial supreme court nominee, Brett Kavanaugh, currently trails in the polls.

Her victory in 2012 was decided by less than 3,000 votes – making Native Americans, who make up about 5% of the state’s population and tend to swing Democratic, a potentially decisive bloc in 2018.

Almost immediately after Heitkamp was elected, Republicans in the state legislature passed the voter ID law. Following court rulings that initially blocked it, 2018 will be the first election the law is in full effect.

Cramer, an arch-conservative, has like other Republicans in the state argued the law is vital to protect against voter fraud. At a debate last week he suggested there was no discriminatory effect and accused the law’s critics of playing “identity politics”.

History tells a different story.

North Dakota, the only state in the union that does not require individuals to register before they vote, has prosecuted just one case of voter fraud in decades. According to the Standing Rock tribal council, there has never been a cases of voter fraud in Sioux county, the jurisdiction that covers all of Standing Rock’s territory in the state.

For some the new laws were a further reminder of the state’s racist past, in which it legally disenfranchised most Native voters. At the turn of the 20th century North Dakota’s constitution gave the right to vote only to “civilised persons of Indian descent” who had ended their ties to tribal government. Like the Jim Crow laws of the south, the discrimination was formally ended with the passing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act – a defining achievement of the civil rights movement.

But since a 2013 supreme court decision weakened key provisions of that law, the voting rights of minority groups like Native Americans have come under frequent attack.

Standing at the top of a hill that overlooked Fort Yates, as autumn leaves swirled in the wind, Chase Iron Eyes looked out over his childhood home.

“This history that we have here is not set up to honour us as human beings or honour our right to participate in democracy,” he said.

“The government didn’t need a physical address to come and steal our children for boarding school. The government didn’t need a physical address when it was time for us to be conscripted into their militaries. But now they need a physical address so that we can exercise one of the most basic principles and tenets of a representative democracy.”

Like many working to get out the vote, Iron Eyes, a prominent activist and former Democratic congressional candidate, was hopeful the new law would only serve to galvanize voters. But he was acutely aware of the challenge in a place battling with an addiction epidemic and unemployment rates over 60%.

“Every election is such a beast. There’s got to be an organized, consistent effort to get our people – disempowered, disenfranchised oppressed people – to give a shit about their destiny. That’s a hard thing to do.”

Over the two days of door knocking observed by the Guardian, dozens of Standing Rock residents said they had already been out to collect new ID documents. But canvassers were concerned by a few incidents that illustrated the strict requirements now in place.

Residents were being told to fill in their forms in blue ink: clerks at the county offices had rejected applications written in black and green. One Standing Rock resident, Dale Ramsey, had his application for a new ID rejected as he had previously listed an address outside the reservation on a separate document. (He had been homeless at the time and so registered at a shelter outside Standing Rock.) As it stood, he would not be able to vote.

The tribe were also concerned that two of the five polling stations inside the reservation would only be open from midday on election day – the other three will be open from 9am.

Volunteers were encouraging voters to cast their ballot early, at the county courthouse, by applying in person for an absentee ballot and handing it straight back with the vote cast. But the tiny offices there were burdened with other municipal duties too.

Out in the remote settlement town of Selfridge, 34-year-old Honorata Defender and three other volunteers were knocking on doors. On one dusty street, 81-year-old James Cowry opened the door, surprised to be receiving visitors.

He had lived in his home for three decades and had never known its formal address. The volunteers told him to call the local 911 coordinator, who would give him the information. But he had still not decided whether to vote.

“I don’t feel for the candidates either way,” he said.

Defender vowed to come back and drive him 30 miles down the road to pick up his ID card later in the week.

“Every vote should count,” she said. “I’ll do all that I can to help you.”