North Carolina flooding proves we need a new way of rating hurricanes

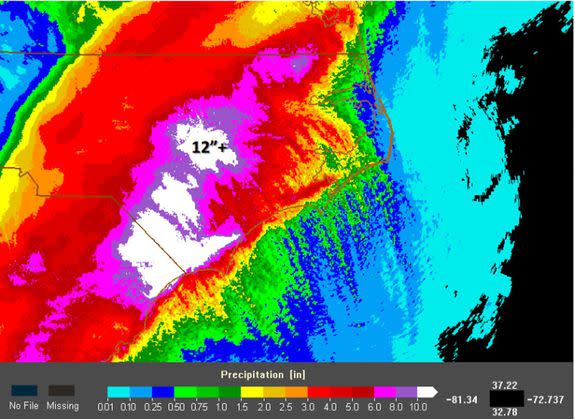

With North Carolina reeling from more than 17 inches of rain from Hurricane Matthew, it's time to face the fact that the way we measure hurricanes and communicate their likely impacts is seriously flawed.

We need a new hurricane intensity metric that more accurately reflects a storm's potential to cause death and destruction well inland, rather than the Saffir-Simpson Wind Intensity Scale, which focuses on the potential for coastal damage from high winds and storm surge flooding.

SEE ALSO: Hurricane Matthew could cause billions of dollars in U.S. economic damage

So far, Hurricane Matthew has killed 22 people in the U.S., nearly half of which occurred in North Carolina. As of midday Monday, an entire town — Lumberton — was being evacuated via helicopters and boats, as a river surged through the entire area. A levee break may have accelerated the flooding there.

Image: AP

The inland flooding illustrates the complexity of these storms. In advance of the storm making landfall, the national media spotlight focused on the potential for tremendous wind and storm surge damage in Florida. Yet in the end, this event may go down in history as North Carolina's worst natural disaster on record, due to heavy rainfall.

Saffir-Simpson only measures wind

Right now, the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Intensity Scale is what we use to communicate how strong a storm is. Developed by engineer Herb Saffir and meteorologist Bob Simpson in the early 1970s, it is based on the maximum sustained winds in a hurricane.

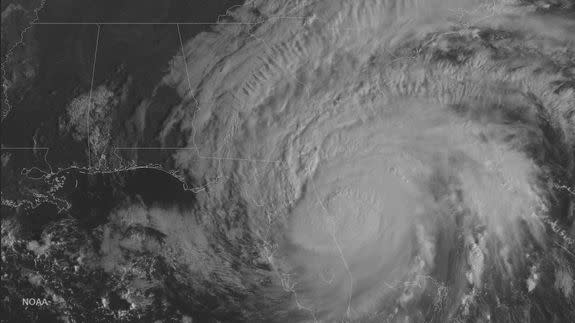

But this ignores the multitude of other threats that hurricanes pose to coastal and inland areas. In the U.S., Hurricane Matthew, which was the longest-lasting Category 4 and 5 storm on record during the month of October, will be remembered more for its water damage — both storm surge and inland flooding — than its winds, which is what the Saffir Simpson Scale communicates.

Image: NOAA

With Matthew, the storm did some of its worst damage when it was "just" a Category 1 storm, slinking along the coast of the Carolinas. The storm's category may have suggested to people that it was not a huge threat to North and South Carolina, when in fact the opposite was true.

The storm combined with a preexisting frontal system and record high amounts of atmospheric moisture, pumped into the air from unusually warm sea surface temperatures, to crank out torrential, flooding rains.

It's long been known that water is the biggest killer during hurricanes. So why do we use a scale that only communicates the wind and coastal storm surge threat?

The answer is that we just haven't come up with a better one yet. Or rather, several have been proposed, but none have become a consensus view within the weather community.

Potential alternatives

For example, a 2006 paper proposed a post-landfall hurricane classification system that would incorporate open water storm surge, rainfall, duration of hurricane force winds, maximum sustained winds, gust score and minimum central pressure.

Each storm would be assigned numerical values for each variable, and then the storm would be assigned an overall value on a scale of 0 to 100.

Image: ohn Bazemore/AP

Of the Saffir-Simpson scale, the paper, which was published in the Journal of Coastal Research, stated: "Its purpose is invaluable in the pre-landfall window; however, the Saffir-Simpson Scale does not accurately account for the total damage in the post-landfall period."

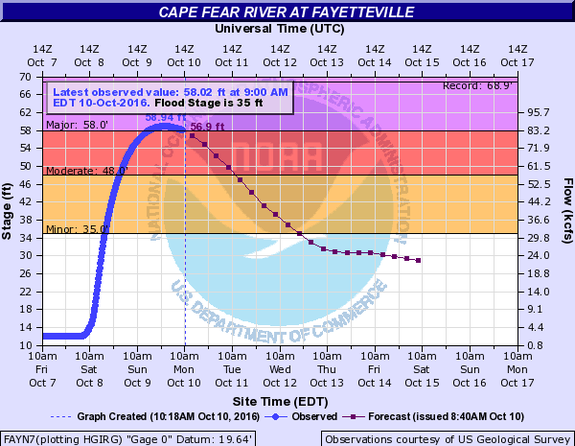

The post-landfall intensity scale may have helped communicate the flood threat during North Carolina's previous record deluge from a tropical storm or hurricane, which occurred in 1999. Hurricane Floyd caused flooding for weeks and killed 36.

In the next week, many rivers in North Carolina are predicted to crest above the Floyd flood records due to Hurricane Matthew.

Jason Senkbeil, a geography professor at the University of Alabama who co-wrote the proposal for a post-landfall hurricane classification system, said the Saffir-Simpson scale is useful because of its simplicity.

"The simple 1-5 ordinal Saffir-Simpson Scale gets people's attention and a 3 or higher usually prompts people to take protective action, or motivates those in low lying surge or flood prone areas to evacuate," he said in an email.

"In this regard the Saffir-Simpson Scale has been and continues to be useful," Senkbeil told Mashable, noting that new storm surge products and graphics are helping to communicate other threats that the scale does not incorporate.

The media, including meteorologists, focused a lot of attention on the threat that a Category 4 storm posed to Florida, and far less to the inland flooding prospect. This was similar to past storms, such as Hurricane Irene, which spared New York City much damage but went on to cause record, devastating flooding in New England.

"Every hurricane is different in terms of the types of hazards associated with landfall and we are doing a POOR job of communicating ALL hazards," Senkbeil said in an email "My scale was meant to be a post-landfall scale but it could be easily adapted to be pre-landfall. Matthew would have obviously been the water danger type as soon as it left Florida."

Image: Eric Gay/AP

"Although several media outlets were warning for potential flooding from Matthew in the Carolinas, too much attention was devoted to the possibility of landfall on the Florida coast and the potential wind speeds above 130 mph," he said. "Matthew only had a 25% chance of making actual landfall in Florida."

Kevin Trenberth, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado, said the Saffir-Simpson Scale "has always been seriously flawed."

However, replacing it, or supplementing it, is no easy task. "The main headline threat is always the wind speed and direct damage, which is always local to the coast," he said in an email. "The storm surge threat is also local to the coast but depends upon rate of movement of the storm and how it synchronizes with high tide: but it is always growing because sea level continues to rise."

"The most widespread threat is heavy rains and flooding," he said, noting that the size of the rainfall threat is related to the size of the storm and the temperature of the ocean where the storm is drawing its energy from.

With Hurricane Matthew, Trenberth said the sea surface temperatures were more than 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, above average for this time of year, across a broad region that the storm drew moisture from.

This added more water vapor to the air, which eventually condensed and fell as torrential rain in the Carolinas.

"So it seems to me that three threats need to be assessed but often aren't, or not adequately," Trenberth said.

Another index that has been proposed is the Cyclone Damage Potential, or CDP. This one can be used to estimate the potential damage a storm will cause to offshore facilities. Greg Holland, a researcher at NCAR who helped develop the scale, says work is ongoing to try to extend it to onshore impacts as well.

"The Saffir-Simpson categories are an excellent approach to providing clear communication on the potential impacts of hurricanes of varying intensity. However, while intensity is very important, focusing on it alone may lead to miscommunication of the actual impact potential," he said in an email.

Image: NOAA

There are still other proposals out there, including a scale that would try to capture the force and area of a storm's wind field, known as Integrated Kinetic Energy, or IKE.

Each of these has its pros and cons, but no single scale has yet been agreed upon and moved forward to an implementation. Hurricane Matthew should be a wakeup call that this needs to happen, soon.

With climate change set to increase rainfall from these massive storms, developing a more impacts-focused hurricane scale that includes the inland flooding issue is going to be even more critical.

Such a scale, if it is successful, could save lives, and prevent people from being caught off guard by torrential, even catastrophic amounts of rain.

Perhaps the people of North Carolina — many of whom have told reporters they were caught off guard by the flooding — will have some suggestions, once they get through this ordeal.