NJ Senate President Scutari failed to disclose details of about $600K in campaign expenses

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

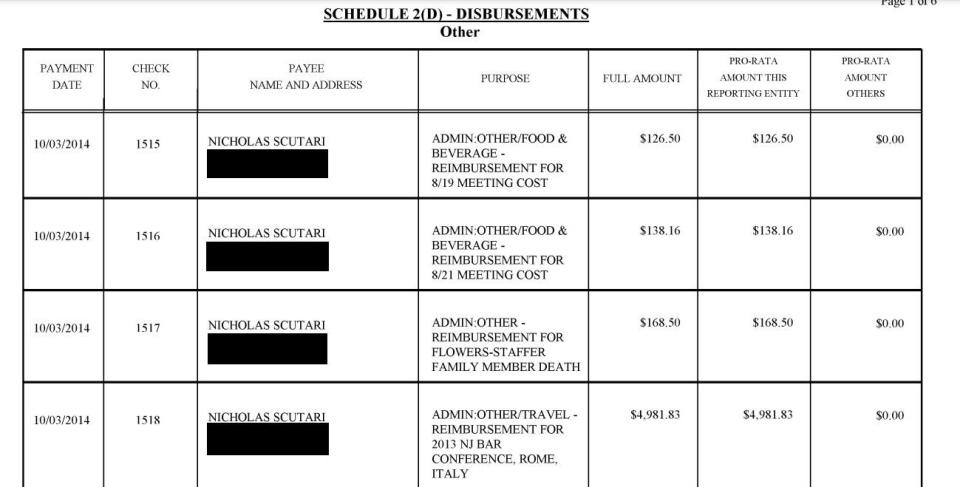

The item was a routine entry in state Sen. Nicholas Scutari’s campaign finance report: On Oct. 3, 2014, his campaign wrote a $4,982 check to cover the various costs of attending a "2013 NJ Bar Conference" in Rome, Italy.

Head of the powerful Judiciary Committee at the time, Scutari was a panelist at the lawyers’ event, held at the luxury hotel Westin Excelsior Rome.

But some key pieces of information were missing from that Rome entry on his report: namely, the specific expenses that Scutari had while on the trip that resulted in the single check back to himself for nearly $5,000.

It has long been a trademark of reports submitted by Scutari, now the Senate president.

Scutari’s campaign failed to properly disclose basic details of close to $600,000 in campaign spending — out of a total $1.8 million over the past 15 years. For nearly 1,000 entries, Scutari recorded expenses as “reimbursements” to himself or staff, failing to disclose the vendors or businesses the campaign had compensated.

State law requires candidates to provide important details about how they spend the campaign donations they receive, including the names of companies or vendors they paid — a requirement that helps voters determine whether money is actually being spent on legitimate campaign expenses, and not personally benefiting or compromising a candidate, ethics experts say.

Scutari often failed to provide those key details.

For more than $270,000 in expenses, Scutari lists himself as the vendor, paying himself back for baseball fundraisers and travel expenses to events ranging from the lawyers’ conference in Rome and two trips to Portugal to a Latino Institute conference in Puerto Rico.

Similarly, for about $320,000 in expenses, Scutari lists as the vendor Edward Oatman, Union County’s manager and Scutari’s former chief of staff, to reimburse Oatman for covering the costs of unspecified food and drinks, travel, fundraising rentals, postage, the partial rental cost of a port-o-john for a Linden picnic, and more in reports to the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission (ELEC).

“Throughout a career in public office that has spanned decades, Senate President Scutari has always filed campaign finance reports in a timely and accurate manner. At no point has he ever received any questions from ELEC about his reports, and they have always been accepted without comment,” said Nick Fixmer, with the Senate Democratic Majority. “We are looking into the issues you raised, and if any additional information needs to be added to old reports, we will do so as quickly as possible.

“Senate President Scutari believes strongly in having a vital, operational Election Law Enforcement Commission, one that operates quickly and effectively to ensure all candidates follow current election finance reporting laws,” Fixmer said.

No complaint has been filed to ELEC about Scutari's reports.

Scutari has been the chief sponsor and defender of the controversial Elections Transparency Act, which Gov. Phil Murphy signed into law last month. Scutari’s core defense — and a talking point shared by other Democrats who came under criticism for backing the new law — was that the sweeping overhaul of New Jersey’s campaign finance system would shed more light on how special interest money flows in and out of secretive dark money accounts, which had grown in popularity.

“This bill in large measure is a transparency act and is going to allow for people to know more about money in politics,” Scutari, D-Union, told reporters in February. “That's what this bill is about.”

But the law could also encourage a new deluge of cash into New Jersey politics, because it allows higher contribution limits and creates new fundraising accounts for powerful political parties.

At the same time, the law hamstrings the ability of the state elections watchdog agency to monitor all levels of elections for campaign finance violations.

The law slashed the time the Election Law Enforcement Commission’s six investigators can take to examine a complaint from 10 years down to two years after a violation took place, and applied the change retroactively, wiping out virtually all current investigations.

More: Pay-to-play: Which NJ politicians received the most cash from government contractors?

More: Murphy signs disputed election finance bill that gives him more power over watchdog agency

So if someone wanted the commission to take a closer look at Scutari’s spending and submitted a complaint — the agency cannot start any investigation without first receiving an official complaint from the public — the staff has less time to examine whether any laws were broken. The two-year clock to investigate can also get used up if a politician under investigation stalls, fails to cooperate or appeals to the administrative courts.

What’s more, the commission is currently toothless. One board seat had been vacant, and the three other board members resigned in protest after Murphy signed the Elections Transparency Act into law. If investigators did find violations, ELEC could not issue fines or penalties until the governor fills the board’s empty slots.

‘An important anti-corruption protection’

Campaigns have wide latitude in New Jersey on what they can use political donations for: Campaign accounts can cover “campaign expenses,” or “any expense … used in connection with an election campaign,” as well as spending that covers the “ordinary and necessary expenses of holding public office.”

Candidates can’t use donor-funded campaign accounts for “personal use,” or for expenses that would exist even if a person weren’t running a campaign, such as a personal mortgage or household food.

That is why the details that Scutari repeatedly failed to disclose, including the vendors or other recipients of the candidate’s spending, are critical to understanding whether funds are being used appropriately, ethics experts say.

“Restrictions on how candidates use funds is an important anti-corruption protection,” said Dan Weiner, director for elections and government at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law. “Because if you donate to a candidate’s campaign and that money just goes to personally enrich them, just being used to buy luxury goods … that is a very dangerous avenue for corruption and bribery.

“And transparency is obviously an important safeguard to make sure that those restrictions are being followed,” Weiner said.

More: ELEC executive director avoids discipline after charges of homophobia, racism and more

More: Here are the major changes in the NJ Elections Transparency Act

State statute lays out what needs to be disclosed: the full name and address of the payee, the date of purchase, and the purpose, amount and check number. Writing “reimbursement” as the description is not enough.

If a campaign reimburses a person for a credit card charge, the report must include the name of the person owning the credit card and the name of the lending institution, the name and address of the vendor, the date, the purpose of the purchase and an itemization of the goods or services paid for.

Statute also requires that such reimbursements be reported as a loan to the campaign committee, which Scutari’s campaign does not appear to have done.

ELEC has fined politicians in the past who listed credit card payments as campaign expenditures without detailing what they were specifically for.

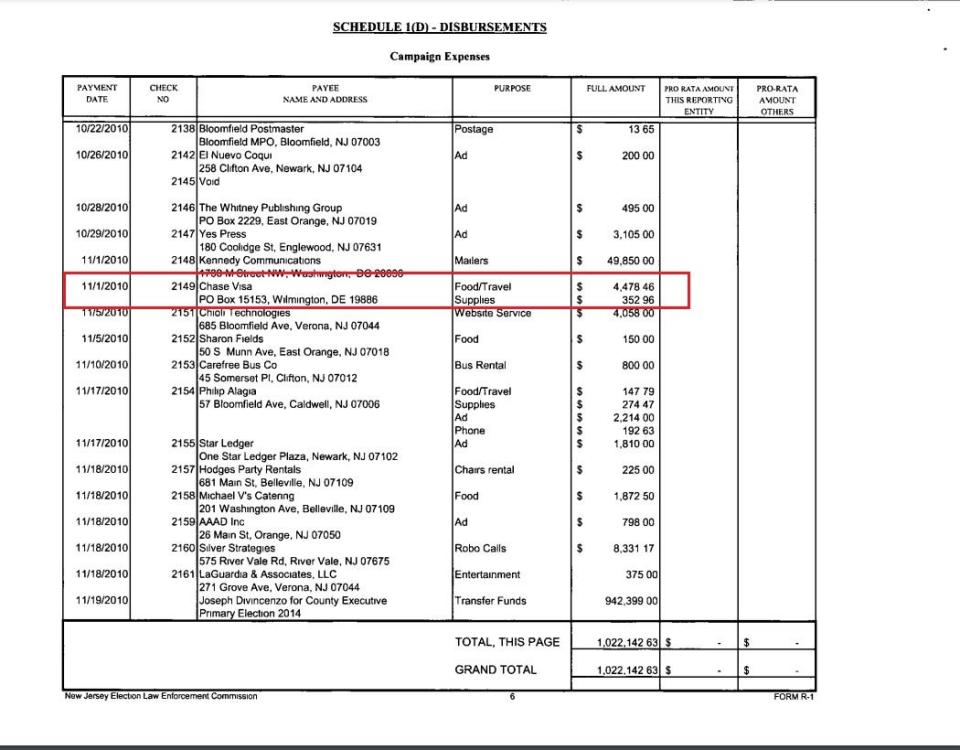

In 2017, Essex County Executive Joseph DiVincenzo settled charges with ELEC that he misused and didn’t properly report campaign funds. He paid a $20,000 fine, though admitted no wrongdoing.

Under the settlement agreement, he was fined for improperly using campaign funds for 43 expenditures totaling more than $13,000 and for failing to report until years later information about 602 credit card transactions worth more than $71,000.

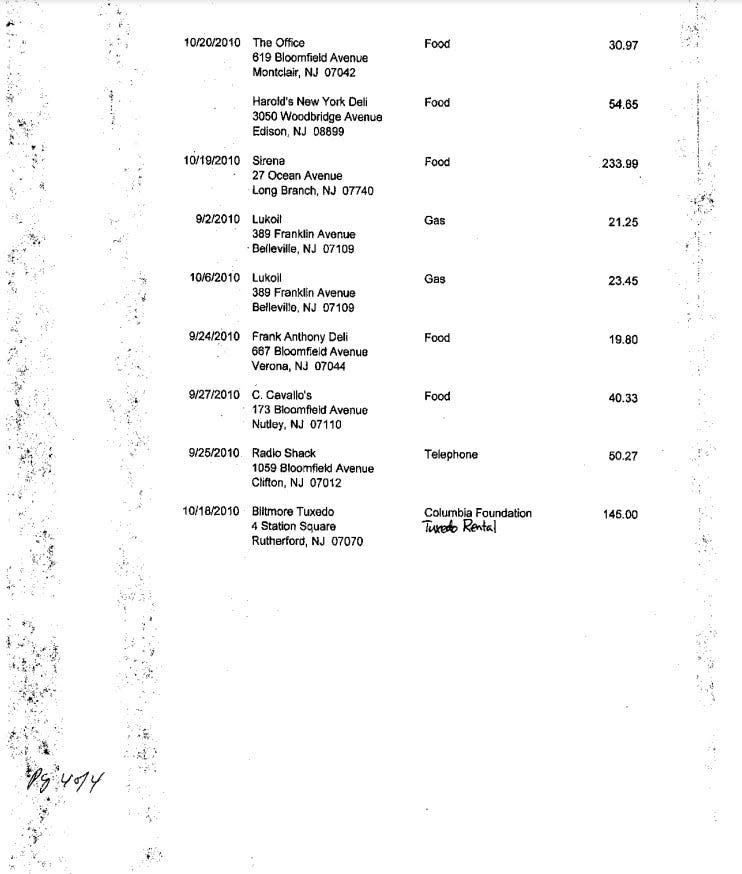

The complaint alleged DiVincenzo billed his campaign for tuxedos; trips to Houston and Puerto Rico; tickets to the U.S. Open, Devils and Houston Astros; his monthly gym membership; and paying parking tickets in his hometown.

His campaign finance reports listed the charges as payments for vague purposes such as “food/travel” and “supplies.” DiVincenzo used his personal credit card for the purchases, then sought reimbursement from the campaign, listing “Chase Visa” as the vendor. After the ELEC complaint was filed, he began filing amended forms with itemized lists of the credit card charges.

In several dozen cases between 2019 and 2021, Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin’s campaign filled out forms in a similar manner, listing $41,000 worth of expenses as “campaign credit card” charges, with the vendor listed as American Express. No complaint has been filed to ELEC about Coughlin's reports.

“Throughout his career, Speaker Coughlin and his team have always worked to file ELEC reports in an accurate and timely manner,” said Iris Delgado, executive director of the Democratic Assembly Campaign Committee. “We are currently working on itemizing these expenses, and will refile the updated report as soon as possible. Speaker Coughlin strongly believes in the Election Law Enforcement Commission and its mission, which is why he sponsored recent legislation granting the commission with more funding for staff and operations.”

Italy, Cuba, Portugal, Puerto Rico

Scutari’s largest reimbursements to himself covered expenses for travel and fundraising events.

Among the campaign’s largest travel reimbursements was a $4,981.83 payment to Scutari in October 2014 for “2013 NJ Bar Conference, Rome, Italy.”

The New Jersey State Bar Association’s annual midyear meeting was held in 2013 at the Westin Excelsior Rome, a hotel that had undergone a $7 million renovation and represented “the height of luxury,” according to the NJSBA’s event page advertising the Nov. 9-16, 2013, conference. The hotel cost 240 to 245 euros a night at the time plus city taxes and fees, the website said.

Attendees could also purchase a $180 winery tour in a private motor-coach to explore Castel Gandolfo, a popular tourist town overlooking Lake Albano, as well as Santa Benedetta, the oldest winery in Castelli Romani. Other tours offered included a $185 Italian Opera “Tosca” tour, a $75 ride in a three-passenger golf cart around Rome’s city center, a $60 outing to the Catacombs or an $85 excursion to the Vatican, the Sistine Chapel and St. Peter’s Basilica. It’s unclear from his campaign disclosure whether Scutari took part in any of the activities, or paid for any with his campaign account.

More: Which NJ special interests spent the most money to influence policymakers last year?

Much of the reimbursement information listed on Scutari’s reports is murky about what the campaign covered.

Other travel reimbursements to Scutari included:

$4,408 for “Cuba Discovery & Education Tour” on March 2, 2012.

$2,821 for “Portugal Conference” on June 5, 2019.

$2,431 for “Portugal Trip 4/27-5/3 2016.”

$1,982 for “Crown Bank Networking Trip 2/21/17.” Scutari listed on his 2021 financial disclosure that he earned less than $10,000 from investments at Crown Bank.

$2,723 for “Latino Institute Conference - Puerto Rico” on Feb. 6, 2014.

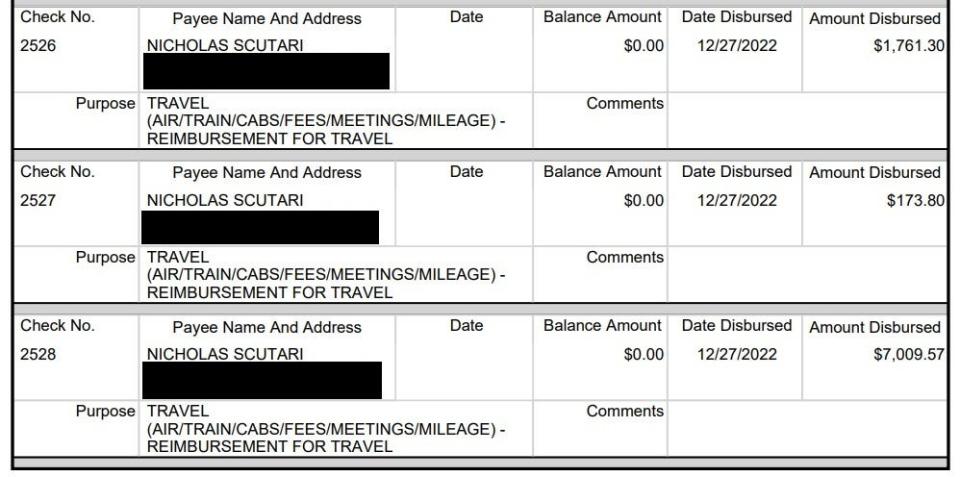

$7,010 for “Reimbursement for travel” on Dec. 27, 2022.

$6,542 for “Travel (air/train/cabs/fees/meetings/mileage)” on May 20, 2022.

Over the past three years, Scutari’s reports listing travel expenses became even less specific, with roughly $34,000 worth of expenses listed only as the generic “Travel (air/train/cabs/fees/meetings/mileage)” — without a note as to what city or what event the expenses covered, or what sort of transportation.

Since 2007, Scutari’s campaign has paid himself and Oatman, the former chief of staff, hundreds of thousands of dollars for expenses related to baseball fundraisers:

$66,938 to Oatman for “Fundraising Rental (Hall/furniture/tents) - Baseball fundraiser” in June 2022.

$41,815 to Oatman for “Fundraising Rental (Hall/furniture/tents) Reimbursement for NY Mets Fundraiser” in January 2019.

$15,140 to Scutari for “Reimbursement for Yankees Fundraiser” in February 2016.

$6,189 to Scutari for “Reimbursement for food for baseball fundraiser” in July 2018.

Past attendees at these events included retired New York Mets outfielder Mookie Wilson and pitcher Dwight Gooden, Assembly Speaker Coughlin and Middlesex County Democratic Chairman Kevin McCabe.

Scutari’s campaign listed reimbursements to himself and Oatman for payments covering catering, ticket deliveries and courier service, travel to the game, parking and “post game” food and beverage — but not the businesses paid.

Other reimbursements with no vendor listed covered meals at meetings, taxis, mileage, flight Wi-Fi, parking fees, holiday cards, stamps, flowers for a staffer after a family member died, and political dinners.

“The whole purpose of disclosure laws are to ensure that constituents can suss out and evaluate conflicts of interest, and to do that effectively, they need the information and data to do so,” said Stephen Spaulding, vice president for policy at Common Cause.

With more information, the public can better determine if they think a campaign is spending its money on actual campaign expenses and spending it efficiently, and whether it’s favoring allies or supporting questionable businesses.

“Is this campaign being run legitimately, or is it being improperly spent on inflated salaries for friends of the candidate or to high-powered officials?” said Stuart McPhail, litigation counsel at Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, speaking generally about why vendors are reported at the federal level.

“Is the campaign paying someone who might cause the public heartburn finding out they are paying, someone who is a scandalous individual?” McPhail said. “Are they paying foreign actors, or are they doing something nefarious with the money? The public has a right to know where this money is being spent.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: NJ Senate president failed to disclose campaign expense details