NFL exports its games to UK, so why doesn't English Premier League do likewise for US?

On a fateful July day 29 years ago, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association stared down one of the boldest decisions it would ever make. Hosting rights for the 1994 World Cup were on the table, and the most enticing of the three candidates was a global superpower of 244 million people. That nation, however, did not have a professional outdoor soccer league. And it had not qualified for a World Cup since 1950.

FIFA measured the massive risks. It took the plunge. And then it fretted for six years as the United States attempted to manufacture soccer interest out of virtually nothing.

“We were all frightened to death that it would be a bomb,” says Charlie Stillitano, now a bonafide soccer promoter, then an industry rookie working on USA ’94. “We were all looking at the Olympics in Montreal,” which lost nearly $1 billion, “like the end of the world.”

But as ticket sales soared above expectations and fans streamed through the gates of mammoth American football stadiums in record numbers, fears were allayed. A fledgling soccer culture was born.

Almost a quarter-century later, it has grown into and perhaps out of adolescence. And it has become the subject of irresistible temptations across the Atlantic.

“The Premier League has looked at North America and the Far East as the final frontier in terms of branding and revenue opportunities,” says Steve Gans, a Boston-based attorney and U.S. Soccer presidential candidate who has worked as a consultant to European clubs. “So it’s had its eye on those markets for a long, long time.”

Its gaze has sparked several global initiatives. Most notably, its clubs embark on annual preseason tours of North America and Asia. They play glorified exhibition games as part of Stillitano’s International Champions Cup in front of tens of thousands of adoring fans, with millions more watching on TV. They capture an audience, which they then monetize through TV contracts and merchandise sales.

“They see unlimited growth,” Gans says of the American market.

But they’re also behind, because when they look across the pond, or maybe now into their own backyards, they see major American professional sports leagues expanding into their territory. The NBA will play its 25th, 26th and 27th overseas regular-season games this winter. The NFL has staged a regular-season game in London every year since 2007, and will play four this season alone. The first of those games is Sept. 24 at Wembley Stadium, where the Jacksonville Jaguars face the Baltimore Ravens, a game that will be live-streamed on Yahoo Sports.

But while Premier League teams schedule preseason games internationally, the league’s regular season remains bound to 20 stadiums across Great Britain. Why? Why hasn’t the marketing-savvy EPL spread its product by hosting actual meaningful games, not just exhibitions, around the globe?

It’s “the next logical step,” says Stillitano, the chairman of Relevent Sports, who confirms he and his colleagues have met with top European leagues and clubs. “Leagues, over time, have talked about it.” Spain’s La Liga could be the first to take the step, as soon as next year. Premier League executive chairman Richard Scudamore said in July that “clubs would like to do it,” and he himself thinks it’s the “right thing to do.”

But, he admits, “there is no plan to do it.”

Because just about everyone else disagrees with him.

*****

“I’ve got scars all the way up my back.”

That’s how Scudamore remembers his first attempt to implement a plan to take Premier League games abroad. It was in 2008. It was dubbed the “39th game,” and proposed the creation of an extra round of fixtures to be played outside of the UK.

“It produced massive backlash and opposition,” says Malcolm Clarke, chairman of the Football Supporters Federation, which represents fans across England and Wales. And, he says, “it should have been quite predictable.”

It wasn’t just the fans who lashed out. Newspaper columnists crucified Scudamore and the league. Even prominent managers condemned the idea. Lord Triesman, then the chairman of the English Football Association (FA), identified four central issues with the plan, and rejected it.

One issue is fundamental, and remains the biggest obstacle today. “The whole of English football has been based on the simple principle that all the teams in all the leagues play each other twice,” Clarke explains. The raw results of those double-round-robins determine everything, from league titles to promotion and relegation.

A 39th game, and therefore a third against one opponent, breaches that principle. It creates an unbalanced schedule, and has potentially drastic consequences. If an 18th-place team were to lose its “39th game” to Manchester United and a 17th-place team were to win its additional match against Burnley, the scheme would cost the relegated club hundreds of millions of dollars.

Unbalanced schedules are customary in the U.S., but never are they the sole determinant of a league champion; and never could they send a team burdened by a harsh schedule tumbling down to a lower division. “If it were just another bad season that the Cleveland Browns were going to have, it wouldn’t matter,” Stillitano analogizes. “But if the Cleveland Browns were no longer in the NFL? You see why people get upset.”

And so nowadays, Scudamore is more realistic. “If it did happen, it wouldn’t be a 39th game,” he said.

Other proposals suggest taking one of the already-ingrained 38 games abroad, but even that would create a home/away imbalance. There are superficially feasible third options, such as taking two of the 38, leaving all 20 teams with 18 home matches apiece.

But none of them dodge the other central issue at the heart of the backlash: the loss of a sacred Saturday afternoon in the stands. Supporters can’t fathom live matches being stripped away from them. Their anger hints at differences between sports fandom in England and the U.S.

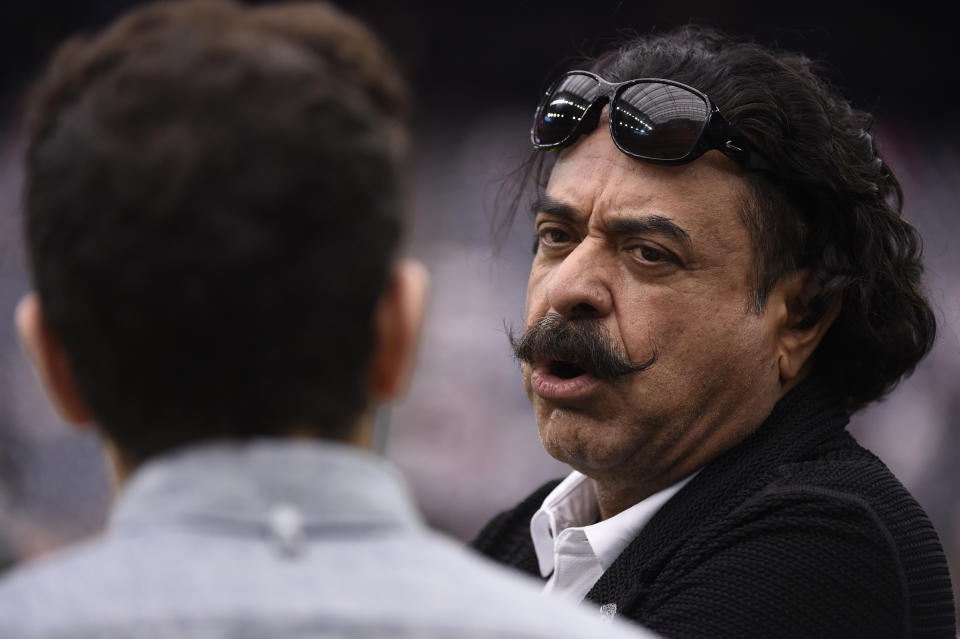

“Soccer is more of a tribal thing,” says Shad Khan, who owns both the NFL’s Jacksonville Jaguars and England’s Fulham FC. The “NFL is more of an open, inclusive thing.”

Khan’s Jaguars have played one of their eight designated home games in London each of the past four years. Outrage, though, is minimal, if not non-existent.

“The fan base is less angry in American sports,” Gans says. “Because being a season-ticket holder at [an English] club is extremely generational, tribal. So the view of possibly having to give up a home game for a team’s ambition elsewhere is more upsetting.”

“It’s cradle to grave,” Stillitano says of English supporters. “Fans are so unbelievably attached to their team, and to the tradition.”

Clarke, whose organization often defends that tradition, sees objections to the Premier League’s proposals as part of a larger resistance to a growing prioritization of foreign fans over local ones. “There is a sort of feeling that foreign owners who come in don’t understand the history and culture of British football,” he says. And with lucrative domestic and overseas TV contracts now the predominant source of the league’s revenue, “people are worried that that’s what dominates [their] thinking.”

Many local fans see an inherent contradiction in that thinking. “The match-going supporters are very much a part of the product that enables [the league] to sell these things for such large sums of money,” Clarke argues. “I don’t think American viewers or Asian viewers would be so interested in watching a game that was played in an empty stadium. So we say, ‘We’re part of the thing that enables you to sell the product abroad. So think about us a bit more than you have done in the past.’ ”

Scudamore insists the league is doing that, at least when it comes to moving games abroad. “Until the fan, political and media reaction is any more warm towards it, it won’t happen,” he said.

And if a new proposal did arise?

“We ran a big campaign [back in 2008],” Clarke says. “And I’m absolutely certain we would do the same again.”

*****

The Manchester Derby, City vs. United, has been contested 175 times since 1881, and up until this past summer, its rich history had been entirely confined to British soil. But on July 20 in Houston, NRG Stadium’s lights dimmed, smoke coated its tunnels, and out from the smoke emerged 22 players, 10 in sky blue, 10 in red. Over 67,000 fans roared; 452,000 more watched on ESPN. United manager Jose Mourinho had insisted prior to the derby that it would be little more than a competitive training session, but he was wrong. It was a spectacle. It captured the attention of an American soccer public that laps up any high-profile match placed in front of it. In a way, it was one of many preseason friendlies that validated the Premier League’s overseas desires.

But it also begged the question: Is taking regular-season games abroad necessary?

“In a lot of ways, the Prem is getting a lot of the benefit anyway,” Gans says.

Or at least six or seven of its members are. In that sense, the idea is more appealing to smaller clubs, who do come overseas, but who can’t fill big stadiums and ride the ICC’s promotional wave. But it’s also the smaller clubs for whom a game in Boston or Beijing wouldn’t be a guaranteed hit. What if Stillitano’s Relevent Sports were tasked with selling West Brom vs. Bournemouth at MetLife Stadium?

“We would promote it as authentic,” he says. But, he notes, “you’re competing against New York City FC, you’re competing against the Red Bulls, you’re competing against the Yankees, the Mets, the Jets, the Giants, the Knicks, etc. So I’m not sure. … We believe that we could make it work, but I don’t think it’s a slam dunk.”

Therein lies the dilemma. These are the discussions happening within Premier League clubs. Fourteen of the 20 would have to vote in favor to sanction overseas games. Do the potential benefits outweigh the concerns?

There’s a sense of inevitability about the globalization of the sport, which blurs with an inevitability of games being played abroad. But the roadblocks are real. Whether they’re unnavigable is the question.

“It’s a sincere question,” Stillitano says. “Is it worth it? That’s something they have to answer. Because you know you’re going to catch a lot of grief. This is the analysis you have to make.”

Yahoo Sports writer Eric Adelson contributed to this report.

More NFL on Yahoo Sports

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell covers soccer – the U.S. national teams, the Premier League, and much, much more – for FC Yahoo and Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell.