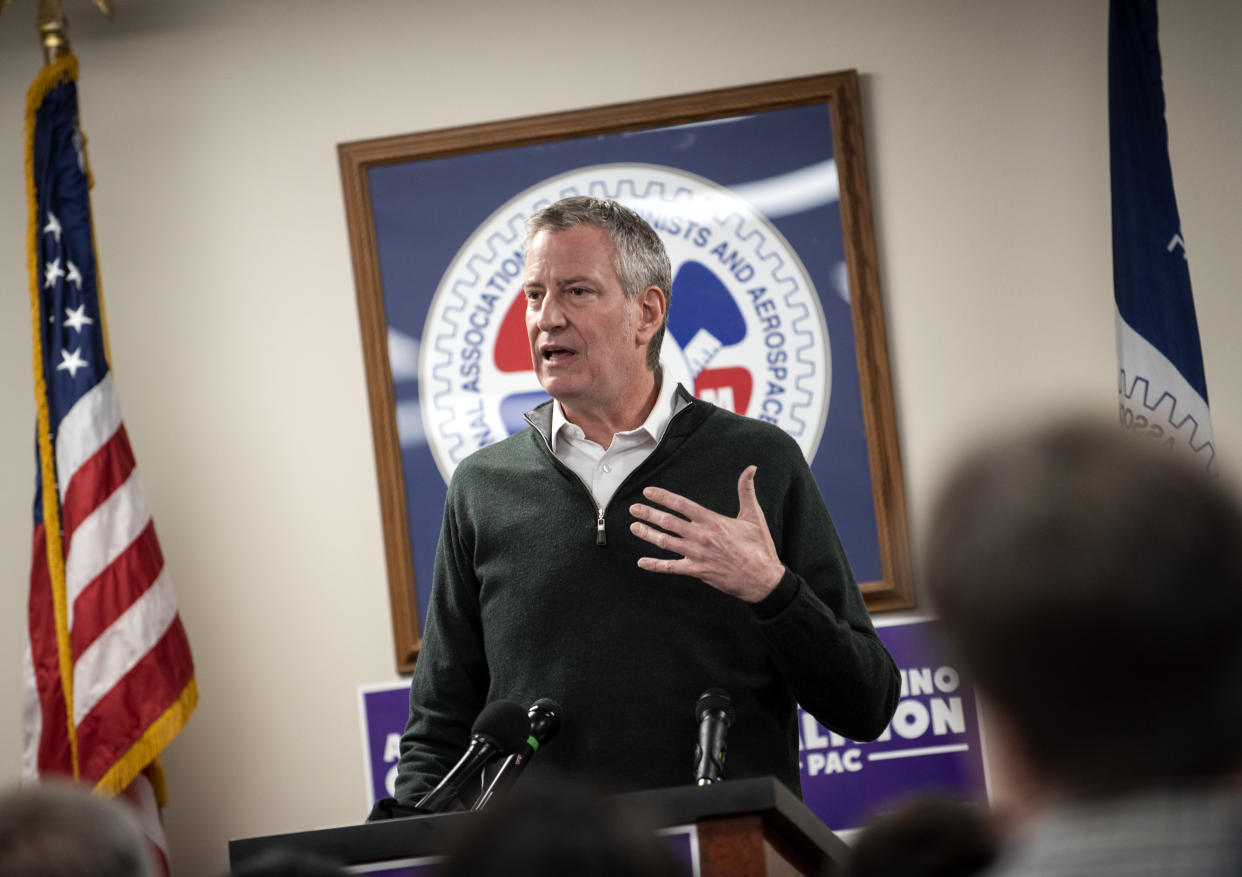

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio makes his case for unapologetic progressivism in Iowa

DES MOINES, Iowa — Bill de Blasio isn’t running for president yet. But there he was in Iowa’s capital on Sunday afternoon, after a snowy Saturday visit to Sioux City. He was one of several national politicians to descend on Iowa over the weekend. The state’s presidential caucuses take place next February, but with a dozen Democrats already in the race to take on President Trump, the window for new entrants is rapidly closing. Campaign staff, after all, are not a renewable resource. Neither are donors.

De Blasio seemed happy to be outside of New York, where he has faced criticism for corruption in his administration, his handling of a public housing crisis and a halting response to a burgeoning homelessness problem. He spoke to prospective voters at a union hall for about 90 minutes, and seemed ready to go for much longer, even as Mitch Henry of the Asian & Latino Coalition, which hosted the event, urged him toward a conclusion.

“Dude, I’m just warming up,” de Blasio said. He also noted that the mood in Des Moines was markedly more cheery than at a customary New York town hall. But he did treat Iowans to one of his more notorious habits, arriving at the union hall about 20 minutes late. He made up for that, however, by patiently answering questions from the audience, showing none of the irritability his constituents have sometimes encountered. He also donned the coalition’s trademark purple T-shirt, posted for pictures and stayed to shake hands and sign autographs, including on a batting helmet for his much-loathed Yankees (the audience was stunned to learn that the New York mayor is a Red Sox fan, an enthusiasm born of his Boston upbringing).

What he didn’t do is say definitively whether he is running for president. “I’m certainly not ruling out a run for the presidency,” he said in response to the question. De Blasio has long-standing ambitions to play a national kingmaker in Democratic politics. In 2016 that effort fell short, as a planned presidential forum on inequality was canceled because of a lack of interest from candidates. De Blasio delayed his endorsement of Hillary Clinton, though he did eventually canvass for her in Iowa.

This time, de Blasio was in Iowa on his own behalf, seeking to usher in what he called “a whole new progressive era in this country,” one based on many of the same initiatives he has overseen in the last five years as the mayor of New York, including universal pre-kindergarten, paid sick leave and expanded public health options.

In previewing what could be his central argument in a presidential primary, de Blasio called the job of New York mayor “the second toughest” in American politics after the presidency. He acknowledged that the phrase had been around for decades.

In fact, it was made famous by John V. Lindsay, who used that formulation in 1969 to explain why his first term as mayor had gone so poorly. Lindsay went on to run for the presidency in 1972, a bid that met an early demise. Once seen as a national figure of the very kind de Blasio seeks to be, in later years Lindsay came to such loose ends that in 1996, he was given a largely meaningless city post by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani simply so that he could have health insurance.

De Blasio’s own model is Fiorello La Guardia, the boisterous progressive who was a close ally of Franklin D. Roosevelt and who implemented many social safety net programs that continue to benefit New Yorkers to this day. But to critics of de Blasio, Lindsay’s dreamy, unrealistic progressivism is closer to the mark. On Friday, New York Times editorial board member Mara Gay published a withering op-ed, “Mr. Mayor, Where Did the Love Go?,” in which she charged de Blasio with putting his own ambitions over the duty of governing.

“Unpopular at home in New York, where his approval rating is 43 percent, his worst showing since January 2017,” Gay wrote, “and apparently bored by the chore of running one of the greatest cities in the world, Mr. de Blasio seems ready to succumb to the temptation that has lured so many other men in his position: a run for president.”

The article was widely shared on social media.

De Blasio’s trip to Iowa began in Sioux City, where he met about 30 people at a bar on Saturday. The crowd that greeted him in Des Moines the following day was about twice that size. Speaking from a podium as the audience ate lunch on folding tables before him, de Blasio eagerly made his case, even though it remained unclear whom he was making that case for, and to what end. As in the past, he indicated that he wants to be a national progressive leader, a position that has been denied to him thus far. But he also allowed that instead of prodding other candidates into more progressive positions, he might want to be such a candidate himself.

As for those positions, de Blasio presented a political vision that would have delighted Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D.-N.Y., the young progressive who seems to be pulling the Democratic Party to the left on issues like income inequality and global warming, causing some consternation and exasperation in the Democratic establishment.

“Too many people think we are the party of elites,” said de Blasio. He talked about the need for higher taxes on millionaires and billionaires, asserting that there was plenty of money in the United States to fund social programs like universal health care coverage, only that that money was currently “in the wrong hands.” He offered full-throated support to labor unions, noting that unlike his predecessor Michael Bloomberg — who is considering his own presidential run — he has signed contracts with virtually all of the city’s public sector unions. Critics have charged that the generous terms of those contracts were intended to win de Blasio political support.

De Blasio also noted that the city’s pension funds had begun to divest from fossil fuels. He said that in order to forfend further global warming, it was necessary to “starve the fossil fuel industry of capital.” De Blasio has been criticized because while he embraces the rhetoric of climate change, he travels almost every day from Manhattan to Brooklyn in a fleet of sports utility vehicles in order to exercise at his favorite gym. There are several gyms within easy walking distance of the mayor’s residence on the Upper East Side.

Showing some familiarity with local issues, De Blasio discussed the need for a forward-looking agricultural policy, using as an example Iowa’s newfound wind-power sector. He also spoke about the candidacy of J.D. Scholten, the Democrat who nearly unseated Rep. Steve King, the pro-Trump conservative whose district had once seemed unassailably red. This was, to de Blasio, proof that there was a silent plurality, if not majority, of progressives across America. Because of that, he said it is high time for progressives to no longer “sound apologetic” about their ideas.

De Blasio certainly didn’t sound apologetic about his own record, or the role he intends to play in the Democratic primary. In response to a question from Yahoo News about Gay’s article in the New York Times, and about broader concerns that he was no longer interested in the mayoralty, de Blasio said that such suggestions were “ludicrous.” He said that it was necessary for him to address national issues and that he was able “to walk and chew gum at the same time.”

In response to a question from a CNN reporter about a rationale for his potential candidacy, de Blasio said that “we have to have a progressive as our nominee,” rejecting concerns that such a progressive would be branded a “socialist” by President Trump. A City Hall staffer who traveled with de Blasio to New York — and who was in Iowa on a volunteer basis — did not respond to a question about whether the favorable reception in Des Moines has convinced the mayor he should be that nominee.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

The Soviets wanted to infiltrate the Reagan camp. So, the CIA recruited a businessman to bait them.

Democrat predicts House will get Trump’s tax returns — but there are a few complications

Habitat for sale: An oil and gas group calls the tune at the Interior Department

Crackdown on opioids has its own victims: People who need them to live

Activists worry that Jussie Smollett arrest will discourage hate-crime reporting

PHOTOS: Eye in the sky: Unusual shots of animals from above will leave you in awe