New book goes inside a forgotten part of Muhammad Ali's legacy

When Muhammad Ali died one year ago, the outpouring of remembrances focused on his boxing career and his humanitarian work. Most obituaries included the phrase “the greatest” or “boxing heavyweight.”

Very few stories devoted much ink to a pivotal period in his life: a four-year court battle against doing military service in Vietnam.

Ali was drafted on April 28, 1967, refused, and was arrested. He was convicted for his refusal on June 20 of that year, sentenced to five years in prison, and banned from boxing for three years. He appealed and did not have to serve prison time during the appeal. And his conviction was overturned by the US Supreme Court on June 28, 1971.

That part of Ali’s life is the focus of Leigh Montville’s new book “Sting Like a Bee.” The book provides a refreshing, surprising lens into a trial that was a crucial part of not just Ali’s life, but American history, but is not well remembered by people under a certain age. It makes a strong case for why Ali’s legacy is bigger than boxing.

Clay vs United States

When Ali objected to fighting in Vietnam, he did so mainly based on religious grounds, as a minister of the Nation of Islam, but also on racial grounds, and on simple moral grounds. Why should he attack people in Vietnam, he reasoned, when black people in parts of America “are treated like dogs.” Besides, he famously said, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.”

Now that he is almost universally hailed as a hero and figure of positive change in our country, it’s easy to forget that many people at the time were appalled by his stance. Even Martin Luther King said that Ali “became a champion of racial segregation and that is what we are fighting against.”

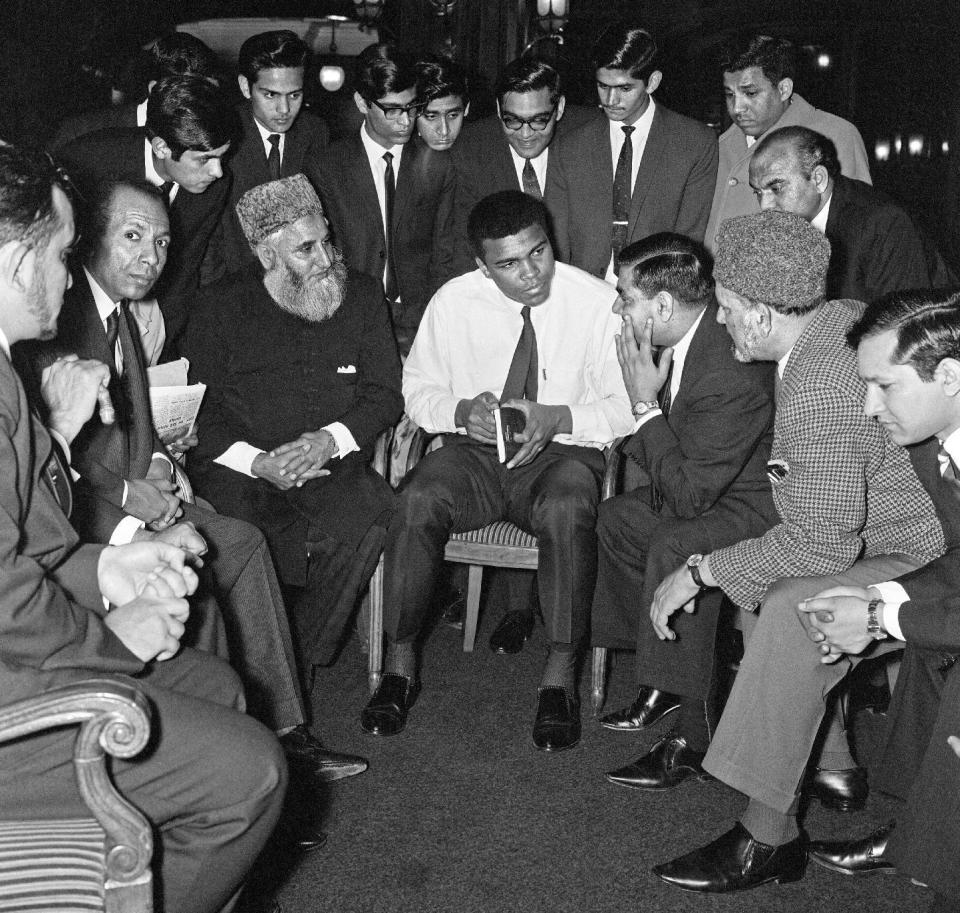

Montville writes that after the assassination of Malcolm X, Ali became “the most prominent Black Muslim in the country.” During his exile from boxing, he spoke at college campuses and made appearances all over the world. “The problem was,” Montville writes, “the part of the world where he lived was not impressed.”

When his conviction was overturned in 1971, some people felt he had benefited from “celebrity justice.” But a bigger factor was that by 1971 the country’s attitude toward Vietnam had soured, which helped his case.

These days, Ali’s objection to the war in Vietnam hasn’t been forgotten, Montville says, but rather has been subsumed amid other parts of Ali’s life and reputation. “His legend kind of grew once he got out of boxing, he became the great humanitarian, and it all kinda got sewn together in one big statue.”

Ali’s business approach

“Sting Like a Bee” opens with an anecdote about how Ali spent the very first boxing money he made: he bought his mother a Cadillac. With the second chunk of money he made, he bought himself a Cadillac. Soon enough, friends told him he should be in a fancier car, like a Rolls-Royce.

But it took a long time for Ali to make big money. At the beginning, he was getting a base salary of $4,000 a year, “and he kind of balked at that, that he wasn’t making enough money,” Montville says. “And he changed his image because of that. He thought he would come out of the Olympics [in Rome in 1960, where he had won a gold medal] and the world would lay money at his feet.”

It was only after his exile from boxing and his trial that he started making millions. When he came back, he soon fought Joe Frazier, who had stepped into the void Ali left behind. Both fighters got paid $2.5 million for the bout—a record then. His first product endorsement was for Brut deodorant. Much later in life, he did an ad for Pizza Hut.

But Ali never fully capitalized on his fame with endorsements and sponsorships, either by choice or due to limited offers.

Montville offers this explanation: “He had all that trouble with the American public, and even when he came back, while he was accepted, there was a core, maybe 35% or 40% who were still against him, and he was still controversial… He never had backers to push him in those directions while he was fighting. And then when he got out of fighting, the opportunities weren’t there because he was sick.”

Indeed, when Ali died, George Foreman, who is widely known for his savvy self-marketing, told Yahoo Finance that Ali was focused on other things than making money. “He caught onto it late,” Foreman said. In 2006, at age 64, Ali sold 80% of his name and likeness rights to CKX for $50 million.

Montville, a lifelong sportswriter who has penned books on Ted Williams and Evel Knievel, treats the trial of Ali with the gravity it deserves, but also keeps the writing breezy and lighthearted with little asides like, after Ali gets his conviction overturned, “Done. Finished.”

Ali, as Montville recalls in the book’s closing, “predicted that boxing, which he mostly meant as the heavyweight division, would die without him. The idea seemed preposterous… That is not the case any longer. Interest has never been lower for heavyweight boxing in the United States.”

Some boxing fans today might dispute that claim, but certainly no current fighter resembles the bombastic presence Ali had in and out of the ring. His four-year court trial had a major part in sharpening that unforgettable presence.

—

Daniel Roberts is the sports business writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter at @readDanwrite. Find more Sportsbook videos here.

Read more:

Muhammad Ali didn’t cash in on his name until age 64