With Nelson Peltz on the Board, Will P&G Finally Break Up?

At the end of Procter & Gamble’s historic annual shareholders’ meeting in October, the climax of the biggest, most expensive proxy fight in corporate history, the two antagonists shook hands. “We’ll talk,” said CEO David Taylor, who thought he had won by a slim margin, though a careful count of paper ballots showed some five weeks later that he’d lost. To which activist investor Nelson Peltz replied, “We’ll talk, but we don’t listen!” (the “we” referring to P&G’s top leaders and directors). Taylor responded, “No, no, no, that’s not true.”

And there we have in microcosm the surprisingly inconclusive outcome of a bitter battle ostensibly over a single board seat, but in reality over the future of one of America’s greatest companies. We know who won the proxy fight, but we have no idea whether Trian Fund Management’s Peltz will succeed in his campaign for major change at P&G. Though his $3.5 billion of company stock gives his views extra heft, as Taylor’s “We’ll talk” indicates, Peltz will be only one director on a board of 11 or 12. The two men’s brief conversation suggests they can’t exchange even a few words without disagreeing fundamentally—reflecting the larger conflict between their sharply different views of P&G’s future. Peltz spent at least $25 million to get himself elected to the board, and P&G spent at least $35 million trying to keep him off. Now they’ll resume their dispute, but with Peltz in the boardroom.

Truth be told, Taylor and Peltz agree on one big thing: P&G needs fixing. They spin it differently. Peltz rails about “P&G’s decade-long history of underperformance.” Taylor sells the upside—that “we’re in a major transformation.” But the underlying reality is that this company has been sputtering for years.

P&G pg isn’t just a business in the doldrums. It’s in a troubling situation we’ve seen before—an aristocrat of American enterprise seemingly past its prime, now facing the profound question of whether it can regain lost glory or continue into a long, slow decline. IBM, General Motors, Sears, and Kodak were at that same turning point about 25 years ago; some would put General Electric in that category today. A comeback isn’t impossible—IBM did it, for a while at least—but history says the odds are heavily against it. David Taylor, 59, and Nelson Peltz, 75, both think they know what needs doing, though their strategies are radically different. All evidence suggests they’ll both remain on this project for a long time to come, maybe several years. So who, if either, can save this company?

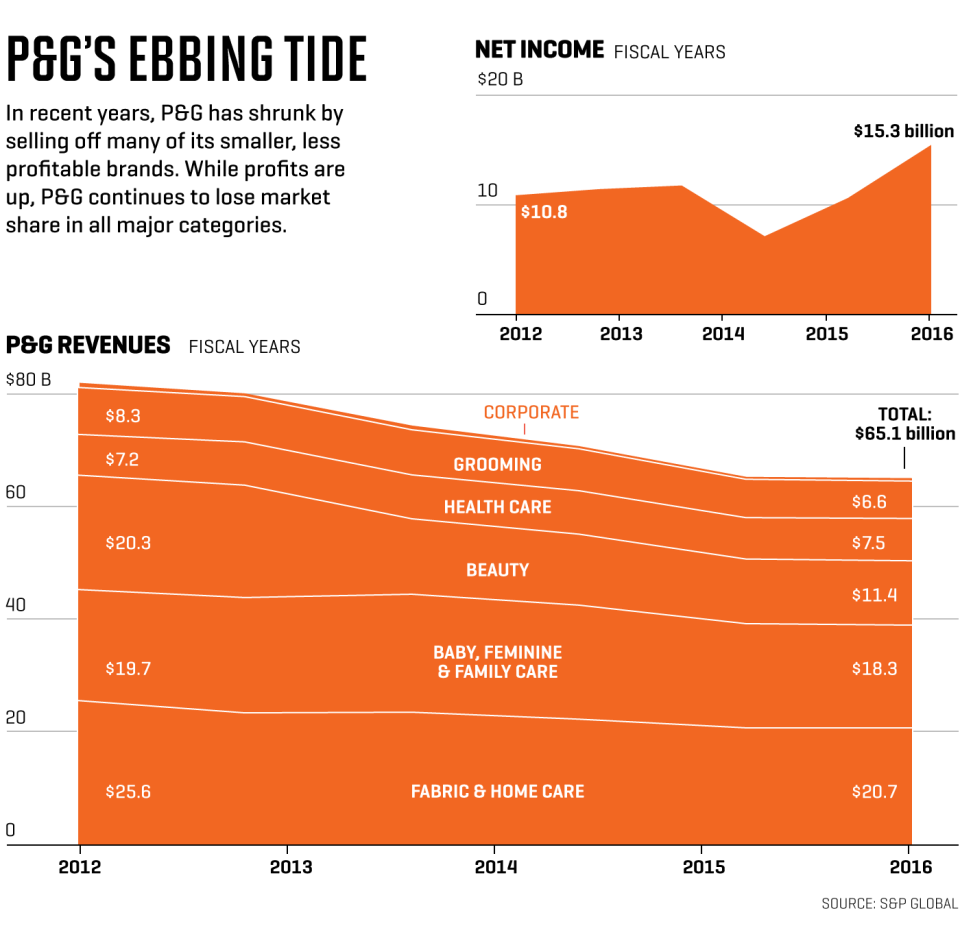

Consider the magnitude of the challenge. Since the U.S. economy’s pre-recession peak, P&G stock (including dividends) has badly underperformed the S&P 500. As the whole consumer packaged goods business slows down, P&G, the industry’s biggest player, has been falling behind major competitors—Unilever, Colgate-Palmolive, Henkel, and others. Dozens of major P&G brands, including Gillette, Crest, and Pantene, have been losing market share; all five of its product categories lost significant share in the past fiscal year (ended June 30). Organic growth, a company-calculated measure that strips out the effects of acquisitions, divestitures, and foreign currency translation, was just 2% last fiscal year, and the company forecasts 2% to 3% this year. Those numbers are below most competitors’, and since they aren’t adjusted for inflation, they mean P&G’s actual organic growth is around zero.

The numbers are damning, and nonfinancial indicators are even more ominous. Today’s best young people might never imagine that P&G was once as glamorous an employer as any company in the world. An alumnus, one of many distressed by its slide, recalls, “When I joined, it was the Google, the Amazon, the Goldman of its day. Its message was, ‘We’re the best company in the world. We create the best products, we improve people’s lives, we export great leaders to the whole world.’ It was hard to get into. They crushed you in the interviews. It was just great. They don’t have that edge anymore.”

Data supports the assertion. Back in 1996, P&G was America’s second-most-admired company (after Coca-Cola) in Fortune’s annual survey of corporate leaders, board members, and stock analysts. As recently as 2009, it was the sixth-most-admired company in the world. It has been falling steadily since, today ranking 19th based on a survey conducted before Peltz launched his proxy fight.

Of course most companies would be thrilled to rank 19th among the world’s most admired, to boast a market cap of $220 billion, to be a Dow component. These are the marks of a champion—and that’s a big problem, which can be summarized as follows: P&G is not in crisis. It can, if it succumbs to the temptation, console itself the way declining organizations have always consoled themselves, by focusing on its current state rather than on the trends. It can point to a hundred ways in which it’s doing well with various products in various countries. The fact remains, however, that the company missed most of the targets the board set for top executives in the just-ended three-year performance period. For the next three-year bonus period, the board declared an organic growth target of 2.8% a year, though Taylor has said he expects market growth of 3% to 3.5% a year. That’s barely treading water. As one former P&G executive sums up, “They set a goal to lose market share.”

Rescuing a big, old incumbent is never easy, but if it’s to be done, the best place to start is with the culture. Inevitably it is first a blessing and eventually a curse. P&G’s titanium-strong culture—rigorous, process-heavy, proud, favoring dedicated lifers—was essential to the company’s success but doesn’t adapt well when the environment changes. It becomes a brake, not an accelerator, in a world of digital disruption and broadly shifting consumer tastes.

P&G claims it recognized the challenge four years ago and has been transforming its culture since then. Taylor vows to turbocharge the change, in part by bringing in more outsiders at high levels. Makes sense, except for a perfect catch-22: The culture has a long history of rejecting outsiders brought in much above entry level—because they don’t understand the culture. P&G has brought in hordes of outsiders over the years through acquisitions, especially its biggest one, Gillette, but few executives remain. “The Proctoids rejected them,” recalls a former exec, using the term for thoroughly acculturated employees. In fact, Peltz says Taylor told him at a meeting last spring that “we cannot bring in outside people at too senior a level or they will fail.” P&G doesn’t deny the quote but says it was taken out of context. A spokesman points to several senior staff executives who have been brought in from outside, though few high-level line managers are outsiders. Overall, P&G says it brought in 200 outsiders above entry level last year, up from 50 a few years ago.

Yet bringing them in below senior levels achieves little. “You don’t change the culture by hiring salespeople,” says Clayton Daley, the company’s CFO from 1998 through 2008, who is now working with Peltz. “The company must hire senior line management from the outside. If your beauty line has been suffering for a decade, why wouldn’t you want to get someone from L’Oréal or Unilever?”

Closely related, and just as important, is the organizational structure, which at P&G has long been impossibly Byzantine, a sprawling matrix of dotted lines that would look like a map of the Tokyo subway if anyone charted the whole thing. For decades, virtually no one below the CEO held full control and responsibility for any profit-and-loss result. And without accountability, performance became less important than blame-shifting. Peltz says it’s still that way, but Taylor says he is thinning “the thicket,” as the near-impenetrable structure is known internally. He has given business unit heads “end-to-end” responsibility for profit and loss, though they still lack full control over spending and marketing decisions. In small markets, teams have “freedom within a framework” to control spending and pricing. Accordingly, Taylor is extending performance bonuses further down into the organization to enforce accountability. That’s progress. Whether it’s enough remains to be seen.

If Taylor can fix the culture and structure, he has a shot at reversing one of P&G’s most vexing problems: the decline of its vaunted innovation machine. The company was long the world’s greatest at the twin skills of creating new consumer products, often after years of scientific research, and then building superpowerful brands under which to market them. The outstanding example is Tide, the first synthetic detergent and the global bestselling detergent by a mile with estimated 2017 sales of over $6 billion.

But breakthrough innovations and new blockbuster brands have been getting rarer. P&G’s last two major hits were the Swiffer line of mops, sweepers, dusters, and related products, and the Febreze brand of household odor eliminators, both introduced in 1998. (Tide Pods, introduced in 2012, have been a highly successful brand extension.) Taylor is responding in part by introducing the “lean innovation” system, which many companies are using enthusiastically. It’s another good idea—if the culture doesn’t reject it.

More broadly, Taylor acknowledges P&G’s problems and says the company is fixing them. Exhibit A in his argument is the stock price. In the two years since he became CEO, P&G stock including dividends has returned 20.4%, not quite matching the S&P 500’s 23%. Middling performance may not seem like much to crow about, but it’s a great deal better than the stock had been doing over the previous two years.

The trouble with this argument is that at least some of the stock’s recent vim is a response to Peltz’s involvement and his reputation as an activist who spurs better performance. The stock price jumped in February when Peltz disclosed his stake, and it jumped even more in June when word leaked that Peltz had nominated himself for the P&G board. The company seems to be getting help from Peltz whether it wants it or not, then citing the stock’s rise in its own defense.

In addition, P&G has been performing financial acrobatics to buoy the stock. The company reported proudly in its latest earnings release that earnings per share from continuing operations had risen a respectable 5.8% in the most recent quarter. But a bit of digging shows that actual earnings from continuing operations hadn’t risen at all. P&G simply bought back a large number of shares, so the per-share number increased. It’s a similar story over the past four quarters: Earnings per share from continuing operations rose 6%, but virtually all of that increase merely reflects a shrunken share count; actual earnings from continuing operations rose just 0.6%.

Increasing EPS in this way does not make the company more valuable. It returns billions of dollars, much of it borrowed, to the shareholders, and the company’s capital structure changes, but that change has no effect on operating performance. There’s nothing improper about any of this. P&G has been buying back stock for many years. But a decade or two ago, when actual annual earnings growth reached 10% or more, buybacks added just a smidgen of extra EPS. Now they’re virtually the only source of increased EPS from continuing operations.

That practice isn’t sustainable, and the company plans to scale it back, saying it expects “core operating profit growth”—not share buybacks—“to be the primary driver of core EPS” this fiscal year. At the same time, it has promised to send even more cash back to shareholders in the form of dividends, to which it is almost religiously devoted. The dividend has been paid annually for 127 years and increased annually for 61 years. “Our first discretionary use of cash is dividend payments,” P&G states in an SEC filing. That’s fine unless it interferes with more productive uses of money, such as the acquisition of innovative new brands, a move that competitors are making and that Peltz advocates. Over the past four quarters, P&G has sent more than 100% of its free cash flow back to shareholders via share buybacks and dividends.

The truth is that Taylor’s transformation plan is incremental, despite the bold language about creating “a profoundly different company.” Like most insider CEOs of great, old companies in need of renovation, he seems concerned about breaking the organization by pushing too hard. That’s understandable, but cultures like P&G’s are astoundingly effective at repelling fundamental change. Peltz’s plan certainly pushes harder, yet it’s restrained, even by comparison with his own proposals at other companies, which have typically been more long-term-oriented than other activists’. He is not suggesting that Taylor be replaced or R&D be cut or debt be taken on.

Some investors argue that neither Taylor nor Peltz understands how troubled P&G really is. They say the only solution is a remedy that activists (including Peltz) have often demanded elsewhere: breaking up the company.

Ali Dibadj, a star analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein who was recently named to Institutional Investor’s All-America Research Team, has been advocating a breakup for over two years. “I think David Taylor is doing his best to change the company,” he says. “Unfortunately, he’s been given a company that should have been changed 10 years ago. I believe breaking up is still the best option for shareholders.”

Big companies argue that they achieve valuable synergies and economies of scale by combining many businesses, but Dibadj says those advantages “appear to be illusory.” Brands that giant companies divest, such as the beauty brands (Clairol, Wella, Covergirl, and others) that P&G sold to Coty last year, do just as well in smaller organizations, he says. “If one does the math on their margins and costs, and compares with smaller competitors, P&G is not more lean. It’s more complex. There are dissynergies of scale for P&G at this point.”

P&G insiders suspect that while Peltz hasn’t called for a breakup, he may secretly favor one. He wants P&G reorganized from 10 global business units into just three “stand-alone” businesses within “a lean holding company.” From that structure to a breakup would be only a small step. A P&G competitor, U.K.-based Reckitt Benckiser, marketer of Lysol, Woolite, and other brands, recently announced it will adopt just such a structure (with two parts rather than three) as of Jan. 1, and analysts speculate the move was a prelude to full separation.

A breakup might well unleash waves of innovation and productivity. But for now, it looks unlikely to happen unless performance gets much worse. That’s a problem regardless of what the best solution for P&G may be, because it supports the slow-decline scenario. Big, successful incumbents rarely flame out when they fail to adapt. More often they stagnate. They change, but not enough. They usually have a strategy for addressing their issues, but it isn’t sufficient, or they can’t execute it. “My biggest fear is that they’ll get organic sales growth back to 3% and will declare victory,” says one alum. P&G insists its ambitions are far greater than that.

At the annual shareholders’ meeting two years ago, a few weeks before Taylor took over as CEO, a shareholder named Karen Meyer asked outgoing P&G chief A.G. Lafley, “What assurance can you give me, the shareholder, that the officers and directors who drove the company bus into the ditch are the ones to get us out?” At this year’s meeting, her husband, Peter, reminded Taylor of that question and then gave his own response to it: “I think the answer has been made abundantly clear by the current data. They can’t.”

That answer may not be correct. Taylor, repeatedly acknowledging the company’s travails of the past several years, assured Meyer that the leaders and directors are utterly committed to outstanding results. And Taylor can succeed even without returning P&G to its full former glory. “I don’t think it can be the Google or Amazon of tomorrow,” says Dibadj. “But it owes it to shareholders to get better.”

Nonetheless, Karen Meyer’s question is undoubtedly the right one, and the answer will become clear in just the next couple of years. Now, when P&G is treading water but not sinking—when the need for change is powerful but not desperate—is when this great institution’s fate is being determined. Procter & Gamble is not in a crisis. We’ll know soon whether it requires one in order to make the needed changes. If it does, it will be too late.

A version of this article appears in the Dec. 1, 2017 issue of Fortune under the headline “Is It Time for P&G to Break Up?” The story has been updated to reflect breaking news.