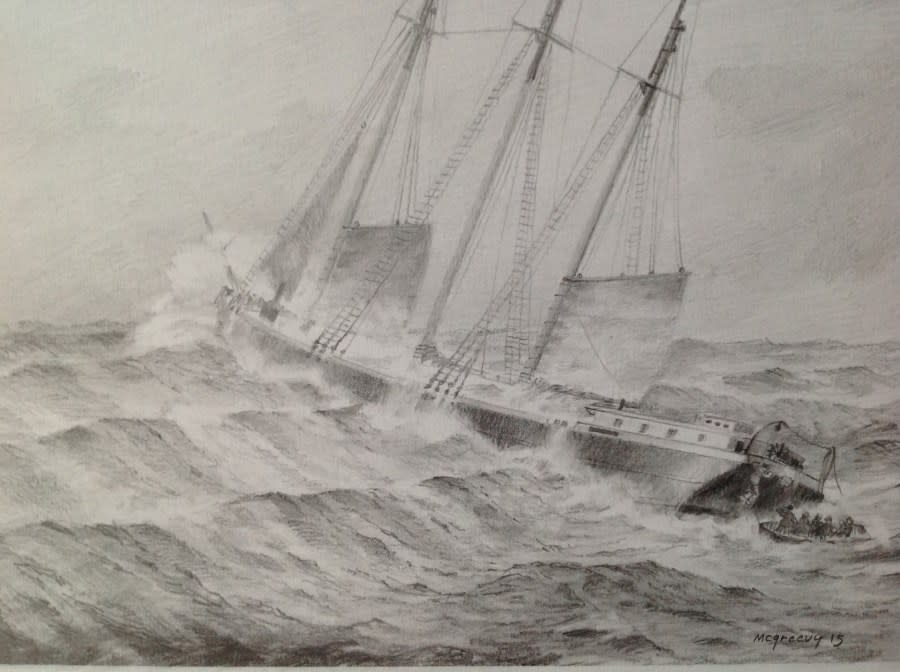

The Nelson: 125 years later, one of Lake Superior’s darkest shipwreck tales retold

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — Monday marks 125 years since a schooner sank on Lake Superior, twisting one of the darkest tales in Great Lakes lore.

Thanks to the crew at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society, that story, as dark as it may be, lives on.

For most nautical nightmares, a survivor has to deal with the loss of their fellow sailors — their work family. Capt. Andrew Haghney lost not only his work family but his wife and child.

The Nelson, a 199-foot, three-masted schooner, was built in Milwaukee and launched in 1866.

Newspapers and the D-Day Invasion: A pivotal role in WWII reporting

On May 13, 1899, the A. Folsom departed, towing two schooners loaded with coal, bound for Hancock, Michigan. On one tow line was the Mary B. Mitchell. On the other, the Nelson, complete with Haghney and his crew.

“Steamships would tow multiple schooner barges behind them for (economic purposes), so they can take as much coal or iron or whatever they were hauling,” Corey Adkins from GLSHS explained to Nexstar’s WOOD. “Sometimes, what would happen during a storm, is that these tow lines would break. The schooner barges then had no power because they didn’t have a motor.”

But a rough storm forced the Folsom, Mitchell, and Nelson to change plans. Newspaper reports from the time say conditions off the coast of Grand Marais, Michigan, turned frigid, with winds regularly breaking 40 knots — that’s more than 46 mph. The trio turned around to seek refuge in Whitefish Bay, on the northeast side of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. But like so many other ships now residing on Lake Superior’s eerie lakebed, the Nelson never made it.

Caught without its tow, Haghney’s crew was able to get the Nelson’s sails up, but the heavy barge was in deep trouble.

Crews battling four-alarm fire in Salisbury

Ice buildup made the wooden ship even heavier, and when the waves caused the Nelson’s load of coal to shift, the schooner was doomed.

“(Haghney) knew the vessel was in trouble. He had his crew and his wife and daughter on board the Nelson, so he put them all into what they called the yawl back then, but basically it was a lifeboat,” Adkins said. “He started to launch it and he was going to stay on board and then hop into the lifeboat with them. But a big wave came, and he got thrown into the lake. When he came up, the lifeboat was still attached to the Nelson, and the crew members and his wife and daughter all went down with that ship. The ship just dragged that all right down with it.”

Haghney had to watch helplessly as his family and crew were lost among the waves.

Capt. A. E. White, on the A. Folsom, also witnessed the wreck firsthand, albeit from a distance. He told local newspapers that the Nelson sunk rapidly, saying it “disappeared as suddenly as one could snuff out a candle.”

In an exact contradiction of the famous maritime adage, Capt. Haghney was the only one to not go down with the ship. He managed to cling to a piece of debris and eventually made his way to the nearby Deer Park Life-Saving Station, a precursor to the U.S. Coast Guard.

“Although nearly dead from cold and exposure, and with ice forming on his water-soaked clothes, he made his way to this place and is now being cared for,” the Grand Rapids Press reported on May 15, 1899.

The Nelson’s story is being shared once again now that the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society has found the ship. Its crew found the Nelson in 2014 off the shore of Grand Marais, approximately 200 feet under the lake’s surface.

A sonar image of the Nelson at the bottom of Lake Superior near Grand Marais, Michigan. (Courtesy GLSHS) Underwater footage of the Nelson found by the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society in 2014. (Courtesy GLSHS) Underwater footage of the Nelson found by the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society in 2014. (Courtesy GLSHS) Underwater footage of the Nelson found by the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society in 2014. (Courtesy GLSHS)

“This is a shipwreck that we have wanted to find for a very long time,” GLSHS Director of Marine Operations Darryl Ertel said in a 2014 news release.

The GLSHS uses a side-scan sonar to analyze the lakebed and look for signs of shipwrecks.

“We call it mowing the lawn,” Adkins said. “He just goes back and forth, back and forth and back and forth, searching for stuff. In the past three years, we have found 13 wrecks. … We find it with the sonar and then we go back with our (remotely operated vehicle) and put that ROV down there and see what it is.”

The GLSHS follows the basic maps of the older shipping lanes and has an idea of where some of the biggest undiscovered wrecks are, but they still use grid mapping to cover the rest of the lakebed.

“The shipping lanes are a little bit different today with the bigger boats, but not that different. Sometimes, during storms, those ships get so blown off (course) that they are not where the historical reports say. We find that, more often than not, that they’re not where they are supposed to be,” he said.

Fallen Wake County K-9 honored at National Police K-9 Memorial Service

Adkins said that as fascinating as the hunt can be, the real mission of the GLSHS is to share the stories of the sailors who sacrificed their lives for others.

“It’s important to our history,” he said. “Without the coal that they were bringing up to those people in Hancock; they use that for heat, they use that for many other things. It’s a part of our history that shouldn’t be forgotten. … They were just out doing their jobs and they lost their lives.”

The GLSHS will continue to search the Great Lakes for more shipwrecks and to tell more stories. But their search for the Nelson isn’t quite over. One thing the crew didn’t find in 2014? Its ill-fated yawl.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to Queen City News.