Neighbors watching neighbors? HOA vehicle surveillance irks some in NC neighborhood

By all accounts, the controversy over surveillance at Princeton Manor began at a pool party last summer.

“Personally frustrated” by a string of car break-ins and a recent burglary in the Knightdale subdivision, a member of the homeowners association board struck up a conversation with a Knightdale police officer at the event, asking what else the neighborhood could do to fight crime.

“Security cameras and doorbell cams are not picking the information up that we need to turn over to help identify these people,” the board member, Chris Willis, recalled in a late summer HOA meeting video shared with The News & Observer.

The officer, Willis said, noted that Knightdale police and other neighborhoods nearby had recently turned to technology from Flock Safety to record license plates and other vehicle information. The private, Atlanta-based firm has grown rapidly since its founding in 2017, marketing its small cameras to law enforcement, companies and neighborhoods.

“Before you know it, there’s a camera at each entrance,” said Keith Gibbs, who’s owned a home in Princeton Manor for nearly 20 years. “And people are starting to say, ‘Well, what is this? What’s going on?’”

At a cost of $2,000 to $3,000 annually per camera, the devices capture license plates and other information on all vehicles that pass by, data that’s retained for weeks and searchable by anyone with access. Their purpose, the company says, is to gather evidence police can use to solve crimes.

The move to install the cameras, though, did not sit well with many Princeton Manor residents, who like other neighborhoods across the country are divided over privacy concerns about the technology and how it’s used.

On Facebook and Nextdoor, Gibbs said, the conversation between Princeton Manor residents shifted from the usual gripes about on-street parking and chatter about social events to concerns about invasions of privacy.

“I understand that we have to have safety and security in our neighborhoods,” said resident Ray Rivera, a retired Wake County sheriff’s deputy. “But when you put a system in that is monitored by regular citizens that captures the comings and goings of over 400 people, 400 houses — to me, that’s concerning.”

Months later, the controversy is still simmering. And the cameras are still recording.

Keeping ‘a historical record’

In its marketing materials, Flock Safety says its products are now active in more than 3,000 neighborhoods and HOAs nationwide. That includes subdivisions in Durham and the Mingo Creek community in Knightdale, right down the road from Princeton Manor.

Knightdale, Garner and Raleigh police departments use the cameras too, tracking tens of thousands of vehicles along city streets and collecting data they retain for 30 days.

But when the two cameras went up in Princeton Manor in the late summer of 2023, Gibbs said there was little clarity on who was able to access what the devices collected and how that data would be used.

“I’m very much against an organization that I’m a part of becoming a private police force and not having policies, procedures, very well trained individuals in place on how to use that data to protect our neighborhood,” Gibbs said.

Skye Creech, who heads up the Princeton Manor HOA board, declined a request for an interview. He wrote in an email to The News & Observer that the board has addressed use of the system with the neighborhood and Gibbs “on numerous occasions.”

“Both the Princeton Manor Homeowners Association and Flock operate within the laws of the State of North Carolina, and we are confident the system operates in such a way at all times,” Creech said.

In the video of the HOA meeting held shortly after the cameras were installed, Willis told neighbors that the board moved forward with Flock not as a measure to track residents, but as a tool to address crimes — “albeit petty, albeit theft and vandalism.”

“Nobody knows that this car belongs to this address or anything like that,” Willis told meeting attendees in the video. “This is simply a historical record so that we can participate, after the fact, if something happens in the neighborhood that we need to help Knightdale PD solve.”

But Gibbs said it’s not hard to “put together a pattern” — which cars park at which houses — to find out who’s who. And even if there’s no nefarious intent now, he said, he’s concerned about the power the system grants to “privately police public streets.”

“If it’s a gated community? Sure. Those are your streets, do whatever you want,” Gibbs said. “But now every person that comes to my home — that I invite to my home — there’s a record of them being in the neighborhood.”

‘Kind of creepy’

Gibbs and Rivera say they aren’t the only community members concerned.

In a neighborhood survey circulated after the cameras were installed, they said, 44% of the 149 residents who responded expressed opposition to the license plate reader system.

There are more effective ways to deter and address crime, Rivera argues. A block watch system, for example, would increase safety and bring the community together, he said.

“This doesn’t,” Rivera said. “All this did was put a wedge between us.”

Once the deputy warden of a Connecticut prison, Rivera notes he’s no stranger to surveillance. But he said many of his questions about the data have gone unanswered.

“Now we have a system that’s not being monitored by any government agency,” Rivera said. “There’s no oversight. There’s no regulation.”

Flock Safety spokesperson Holly Beilin said HOAs using the company’s devices have much less capability than law enforcement — they can’t receive alerts on stolen vehicles and missing persons, for example.

“They’re not investigating crime,” she said. “They’re literally just providing evidence to law enforcement, and we encourage them to share directly with law enforcement.”

But neighborhoods that use Flock technology do have the same auditing tools as police and sheriff’s departments.

“An HOA board can actually audit what their other board members — or whoever has access to the system — is searching on,” Beilin said. She argues those features make Flock products superior to traditional video cameras, where “there is no ability to understand what user is looking at something and who is searching, when they’re searching.”

Beilin said the company provides sample policies when they sign up new HOA users. But she said it’s up to individual neighborhoods to create and enforce their own rules for how to use the system.

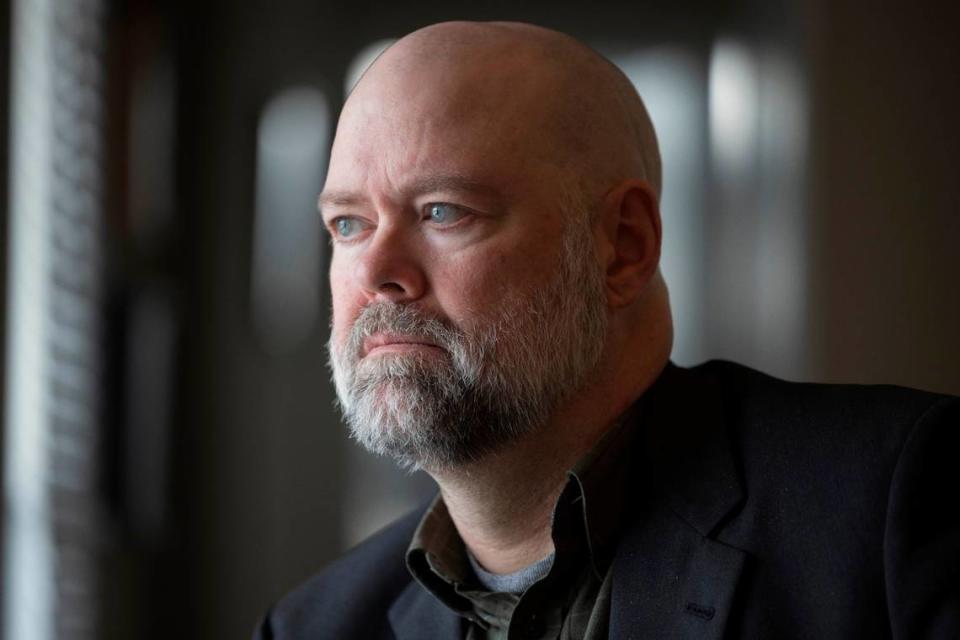

Gibbs, who ran unsuccessfully for a seat on the HOA board this year — prompted by his opposition to the board’s handling of the Flock rollout — said he’s not completely opposed to the technology. He generally trusts law enforcement to use license plate readers responsibly, he said.

“A lot of positive policing activity has come from Flock when used in a fashion like it is in Garner or wherever, where it is on major roads and actively scanning databases for warrants that can be tied to a license plate,” Gibbs said. “That’s because you have an active police force doing that.”

But he’s not convinced that the two-year, $10,000 contract he said the neighborhood signed with Flock is worth it. Neither is Rivera, who said that the devices are just “kind of creepy” in addition to being money poorly spent.

“It’s just a stark reminder, every time you come in here, that somebody’s watching you,” Rivera said. “Why? What the hell did I do wrong?”