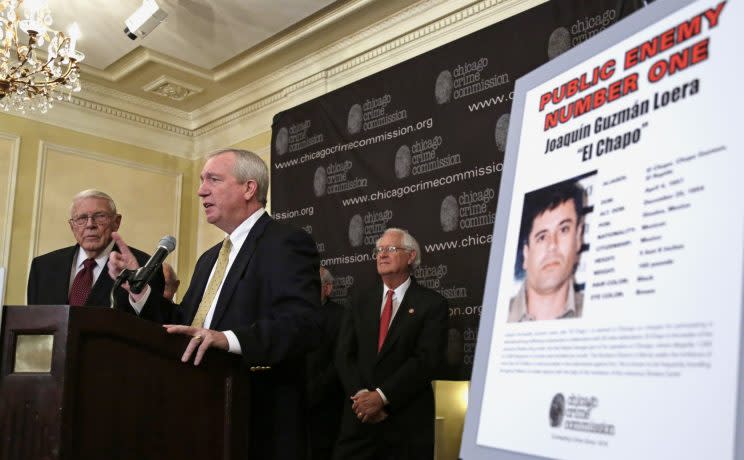

Nearing trial, extradited drug lord El Chapo returns to court in Brooklyn on Friday

The infamous Mexican drug lord known as “El Chapo” will appear in federal court in Brooklyn on Friday for the third time since he was extradited to the United States hours before President Trump’s inauguration in January.

The change of administration has resulted in the resignation of Robert Capers, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York who was the lead prosecutor in the government’s case against El Chapo. But the prosecution, now led by acting U.S. attorney Bridget Rohde, continues to pursue the case against the head of one of the world’s biggest international criminal enterprises.

Guzman, whose real name is Joaquín Guzmán Loera, has pleaded not guilty to 17 criminal charges relating to his long-standing role as head of Mexico’s powerful Sinaloa drug cartel, and if convicted he faces a mandatory minimum sentence of life in prison. At Friday’s hearing, Judge Brian Cogan is expected to set a start date for what’s sure to be a riveting trial — but both sides will get their chance to address a few other issues that have arisen since El Chapo’s arrival in New York.

The first order of business on Friday’s docket will be addressing concerns raised by the prosecution about Guzman’s defense team.

Although the government contends that Guzman’s enterprise has made him one of the richest people in the world — prosecutors are seeking $14 billion in forfeitures — the drug lord is currently being represented by a team of court-appointed public defenders led by Michelle Gelernt and Michael K. Schneider of the nonprofit Federal Defenders of New York, Inc.

In addition to questioning Guzman’s financial eligibility for public counsel, the prosecution has also suggested that the lawyers assigned to Guzman’s case present potential conflicts of interest because Federal Defender previously provided legal services to several potential cooperating witnesses and former Guzman associates turned government informants.

In its letter to Judge Cogan on April 21, the prosecution noted that “to date, the defendant has met with 16 private attorneys to explore the possibility of retaining counsel.”

But while the government acknowledges that Guzman will probably hire private attorneys eventually, ditching the Federal Defenders will hardly eliminate all potential problems with his defense.

In a separate set of letters submitted the court, the government also expressed concerns about the involvement of foreign nationals — such as attorneys who previously represented Guzman in Mexico — with his defense team in New York.

On Feb. 24, prosecutors submitted a letter to Judge Cogan requesting a protective order that would require any foreign nationals working with the defense team to be vetted by the government and receive court approval in order to access sensitive materials related to the case.

A subsequent letter submitted on March 6 clarified that the request “is not rooted in a categorical distrust of foreign nationals.”

Rather, they continued, “it is rooted in the defendant’s demonstrated history of relying on foreign professionals, including foreign attorneys, to further his crimes; his proven ability to corrupt officials at all levels of government; the Sinaloa cartel’s expansive international reach; and the reality that foreign nationals may much more easily evade the court’s jurisdiction — and thus the consequences of violating the Proposed Order — than United States citizens.”

Because of all of these factors, they argued, “there is a significant risk that Sinaloa cartel members, who are also employed as attorneys or investigators, will attempt to infiltrate the defense counsel’s team to gain access to the Protected Material, which they will be able to use to harm witnesses and thwart ongoing investigations.”

In an interview with Univision, Mexican attorney José Refugio Rodriguez confirmed that he and two other members of Guzman’s legal team from Mexico were working with his New York-based attorneys at the cartel boss’s request. While he said they cannot represent Guzman in the United States, Refugio Rodriguez told Univision that he and attorneys Cynthia Castillo and Carlos Castillo were advising Guzman’s defense team on legal strategy and intended to visit their infamous client in jail.

Refugio Rodriguez did not contest the prosecution’s right to investigate members of Guzman’s defense team. However, he told Univision that he objected to what he considered the government’s characterization of Guzman’s Mexican lawyers as possible criminal accomplices. This, he argued, violated Guzman’s right to the presumption of innocence.

Judge Cogan plans to address concerns relating to Guzman’s defense team, who have also been busy flooding Cogan’s docket with issues of their own.

Just over a year ago, Guzman was reportedly so desperate to be freed from the inhumane treatment at Mexico’s Altiplano prison — the same maximum-security facility from which he’d escaped the year before — that he urged his lawyers to expedite the extradition process in hopes of being more comfortably incarcerated in the United States.

But the U.S. government had no intentions of making things comfortable for the notoriously slippery narco, who has already managed to escape from not one, but two maximum-security prisons in Mexico.

Upon Guzman’s arrival in New York in January, Capers and Arthur G. Wyatt, head of the Narcotic and Dangerous Drug Section of the U.S. Justice Department’s criminal division, explained the need for Guzman’s pretrial detention in a detailed, 52-page memo (PDF).

Based on his previous prison breaks, the severity of the charges against him, and his demonstrated “ability to tempt all but the strongest of individuals with large cash bribes,” they concluded, “it is difficult to imagine another person with a greater risk of fleeing prosecution than Joaquín Archivaldo Guzmán Loera.”

Accordingly, Guzman has been held in solitary confinement at Manhattan’s Correctional Center, or MCC, a high-security federal jail whose roster of well-known inmates have included Bernie Madoff and the accused former boss of the Bonanno organized crime family, along with several al-Qaida operatives.

In addition to complaints about the notoriously harsh conditions at MCC’s perpetually lit solitary wing, known as 10 South, which convicted U.S. Embassy bomber Ahmed Ghailani reportedly described as worse than Guantanamo Bay, Guzman’s defense team has submitted several complaints about additional restrictions, the Special Administrative Measures, or SAMs, the Justice Department has imposed on Guzman. One of these prohibits in-person visits with anyone other than his attorneys.

Defense attorneys have repeatedly petitioned the court to vacate the “draconian conditions of confinement,” which they argue violate Guzman’s “Sixth Amendment rights to have effective assistance of counsel, develop a defense, conduct a meaningful investigation, and his right to a fair and impartial jury; his Fifth Amendment right to due process; and his First Amendment rights to free speech and freedom of religion.” They have also asked Judge Cogan to let a researcher from Amnesty International investigate the conditions of Guzman’s confinement.

Guzman’s lawyers were slated to make their case for these and other requests at Friday’s hearing, but were preempted by an order filed by Judge Cogan on Thursday afternoon. In the order, Cogan denied a number of the defense requests, including their petitions to vacate all SAMs and the request for an Amnesty International investigation.

Cogan did grant Guzman permission to communicate with his wife via screened letters.

“If defendant would like to send his wife and infant children a personal message or they would like to send those messages to him, this can happen, subject to review by the screening agencies,” Cogan wrote. However, phone calls and in-person visits, through which concealed messages can more easily be transmitted, are still forbidden.