NC preschool tuition costs as much as a mortgage, and doesn't pay workers a living wage

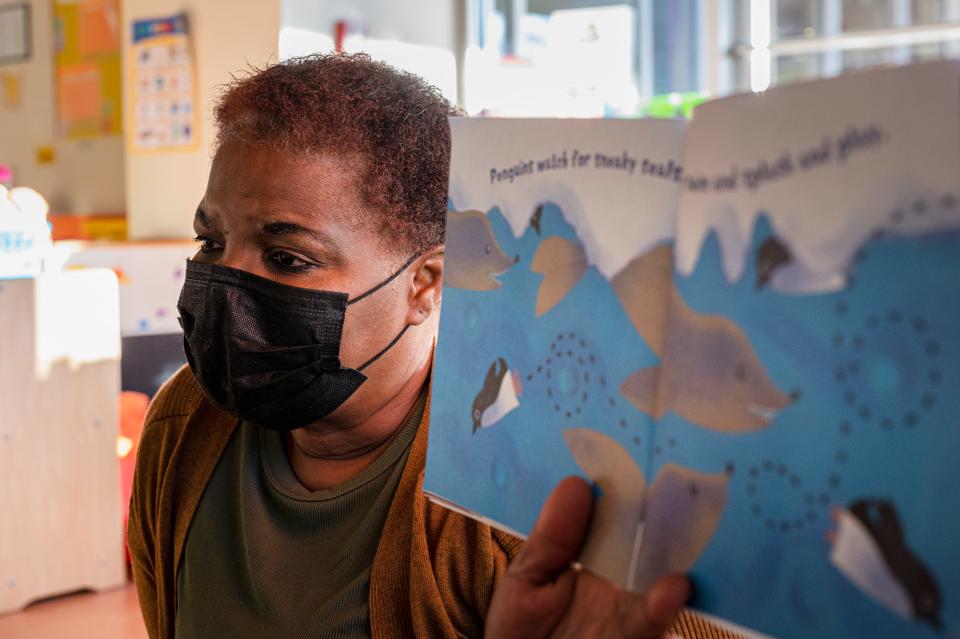

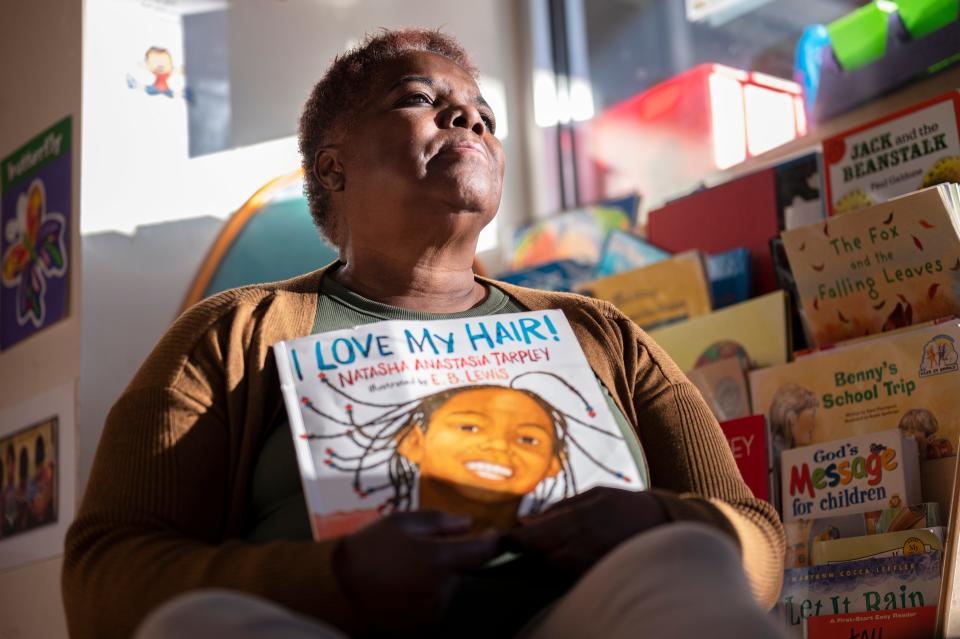

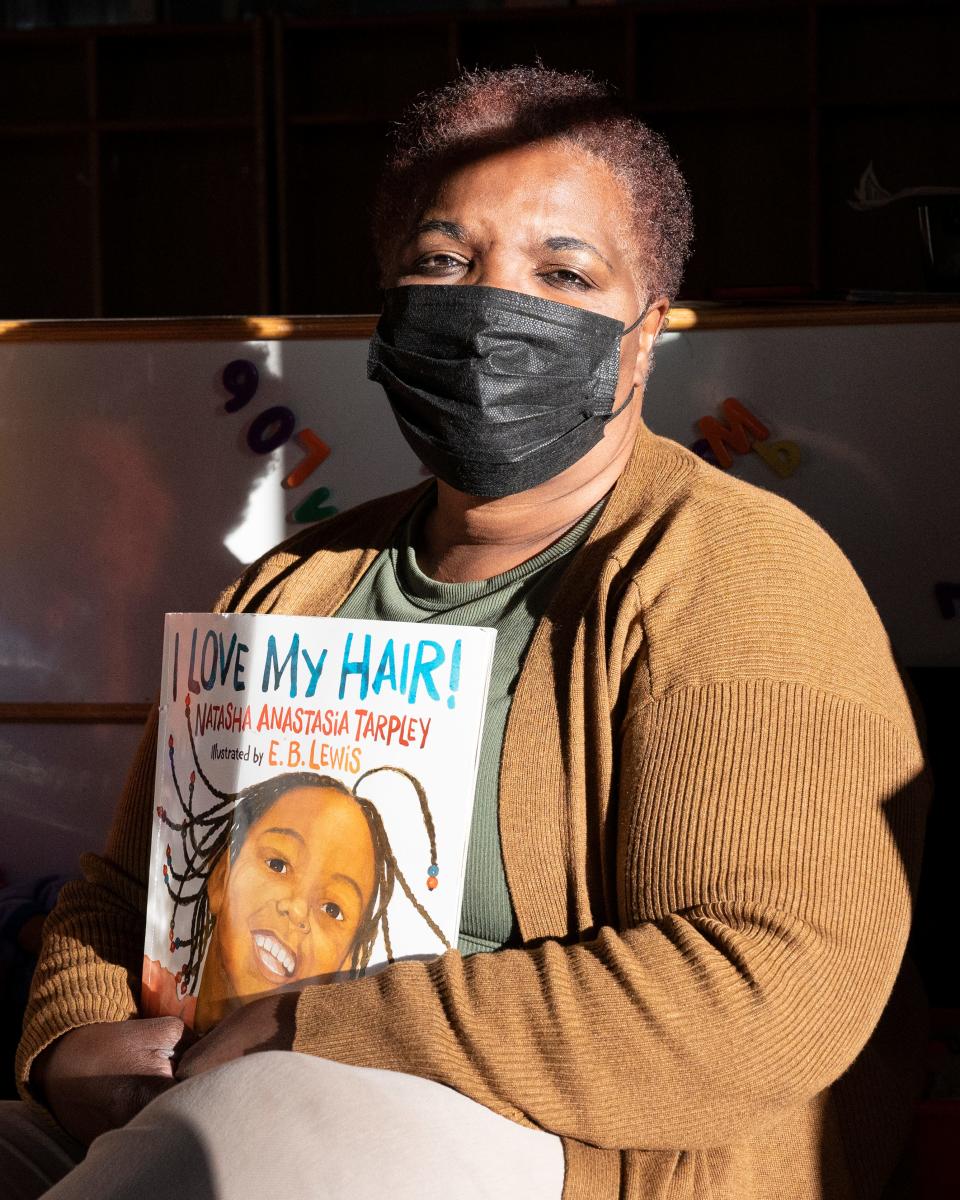

The sun poured into preschool teacher Priscilla Rowell’s 4-year-olds class Nov. 16 at Excel Christian Academy in Burlington, N.C., lighting up the acorn cutouts, the musical instruments, the alphabet mat and 11 children there to learn. Or, in the case of one small boy fetching his mask after breakfast, to dance.

“When you hit the carpet and we start learning I want you to keep that energy,” said Rowell, a short woman with close-cropped hair, sporting sneakers and a breast cancer awareness lanyard. She turned to the rest of the class: “How do we read? Silently.”

They did that, and much more, over the next two hours. Here is a partial list of the activities Rowell conducted with assistant May Carpenter, 66: serving cereal, correcting manners, reviewing the days of the week, explaining hibernation, practicing the sight words “up” and “at,” policing masks, giving a dramatic reading of the book "We're Going on a Bear Hunt," helping kids write the letter W, reviewing one child’s needs with a speech therapist, coaching kids to zip up their coats and leading everyone outside, at which point she began walking herself.

Self-sufficiency matters, she said. “My son, I regret to this day I didn’t let him zip up his own coat.”

Rowell has three children and is “mimi” to four, biological and not. She’s 62 and has worked with children for more than 30 years, including 24 years in public school. Two years ago she earned her associate’s degree, fulfilling a life’s dream. And for those two hours of work in November at a top-ranked center, she made $25. Before tax.

Every weekday morning, millions of parents in this country hand over their young children to workers — almost all women, mostly non-white — who earn less than the person who hands over a chicken sandwich from the drive-through. That’s the reality driving a national child care staffing shortage that threatens not only parents but the economy as a whole.

Pre-pandemic, North Carolina had about 37,400 early childhood workers caring for 734,550 children, according to the University of California, Berkeley. Those numbers dropped during the first months of COVID-19, but now child care centers are trying to rehire to higher staffing levels than before, the North Carolina Child Care Resource and Referral Council found. They couldn’t do it. Three quarters were struggling to hire and half were having a hard time keeping teachers, even after nudging wages up $1/hour.

Early education matters for children, half of whom enter public kindergarten in North Carolina not prepared, according to state data. Perhaps more urgently, it matters for the economy. COVID-19 has revealed to non-parents what parents already knew: You cannot work for wages if you don’t have child care.

That’s why advocates call preschool teachers “the workforce behind the workforce.” But even with dedicated, inspired teachers like Rowell, centers can't find staff. The system is not working. And it has to.

“For us to have a viable economy, we must have care,” Child Care Services Association senior vice president Linda Chappel said.

'A lot of people wouldn't do it'

Rowell has almost as much energy as her students. She wakes up at 4:30 a.m. by choice, “looking forward to coming to work,” she said. “I get hugs from all the babies. She takes a walk and does a little devotion before arriving at Excel at 7:15 a.m. As she finished her associate’s degree, she had custody of two children and worked two jobs. When asked how she graduated with that workload, she said, “Trust in the Lord and keep pushing.”

Rowell wanted to be a mother when she was a child. “And then I took it a step further,” she said, caring for other people’s children. She’s always gravitated toward service jobs. “A lot of people wouldn’t do it. But I feel like it’s just as important.”

It is. Study after study has found that high-quality preschool improves everything from high school graduation to adult earnings to criminality. Nobel-winning economist James Heckman calculated that a dollar spent on early childhood education could have as high as a 13% annual return on investment.

You don’t have to cite stats to Rowell. One of her former students is now a fourth-grader in the Excel after-school program. “I remember when she stuttered and struggled with reading,” Rowell said. Now she reads to the 4-year-olds. “That just gives me a good feeling.”

Rowell has seen the long haul. “Some of my students, I now have their kids,” she said. “That makes me feel good, that people through the generations believe in me.”

Not that they necessarily understand what Rowell does. Preschool staff aren't babysitters. They don't just change diapers or hold bottles or demand good manners. They teach.

Four year olds at Excel have a structured curriculum, published by OWL. Rowell's favorite moment of the job is when she teaches a new skill “and at least half of them grasp it.”

That week, the focus letters were R and W. “Down the hill, up the hill. Down the hill, up the hill,” she coached, tracing a W in the air. The students clutched their fat pencils and wrote. Rowell leaned over to look at a boy who was getting things a little backwards. “You’re making great Ms!” she said. “Don’t get frustrated. You can do it.”

The job might be especially challenging now that COVID-19 has kept so many children out of centers, and more isolated from socializing and playing with others.

“People don’t understand the significance of those first 2,000 days of a child’s life,” said Davina Woods, Rowell’s former supervisor, who now owns a center for babies and toddlers around the corner from Excel. “Brains are not born. They are built.”

Woods thinks the inaccurate stereotypes of what preschool teachers do are why the salaries are so low. The Illinois governor’s office wrote in a 2019 report that the early childhood education market “functions because ECE professionals forgo a living wage aligned to the sophistication of their work.”

'There's no profit!'

Just how bad is the pay? Bad. Before the pandemic, the median wage for a North Carolina child care worker was $10.62 an hour. Close to one in five lived below the poverty line, the University of California, Berkeley found. It's worth remembering that in the South, this job was once literally slave labor.

Rowell has done the math. Yes, she earns only $12.50 an hour. But Excel is one of the rare independent centers that offers paid time off and health insurance. Not only does she love working with children, but the extra dollars in fast food and retail don’t compensate for the instability of constantly changing schedules and no health coverage, she said. Rowell has diabetes and kidney disease, and is a 22-year cancer survivor. (It was “1999, Prince, and I was going to party like it was 1999,” she said, ruefully.)

However, not everyone shares her priorities. Woods, who wakes up even earlier than Rowell, left Excel last year to open Genesis Child Development Center for infants and toddlers. She jumped from a five-star center she had helped build into sustainability into the crevasse of the child care staffing crisis.

“I opened up Genesis and I can’t find one single person,” she said. “I never thought it would be this difficult just to build me a team.” Finally she successfully begged other centers to loan her two teachers. Both were new to the profession, and Woods could pay them only $10.50 an hour, without benefits. “I told them today, hey, Chick-fil-A’s hiring, $14, $15 an hour,” she said.

Loading...

That inability to hire staff has a direct impact on families. “Our phone rings every single day,” Woods said. With parents lucky to get even three months of unpaid leave, “Infant spaces were always prime – people would have to put their names on waiting lists as soon as the stick turned pink.”

Now, it's even harder. Licensed for 30 children, in November, Genesis could accommodate only 12. In December, the omicron variant spurred quarantines that kept staff home.

Ironically, both sides of the caregiving relationship feel it in their wallets. At the same time that child care pays unsustainably low wages, it’s painfully expensive for families. Excel charges $175 per week for a 4 year old, 7 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., a standard rate. At 52 weeks, that adds up to more than $9,000. More than the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Woods sees the paradox: “for a family’s tuition to be as much as their mortgage, and for the people who are providing their care to make minimum wage.”

It’s mostly because child care requires a lot of staff. For infant care, centers are required to have at least one caregiver per five babies, and for quality, the ratio should be one to four, according to North Carolina standards. Then there’s rent or mortgage, utilities, food, payroll taxes, workers’ comp, liability insurance. Baby wipes. To say nothing of the colorful educational supplies that fill Rowell’s classroom.

“The expenses are enormous,” Woods said. And “the cost for tuition very, very rarely offsets the cost of providing care. What drives tuition is what parents can afford.” The accounting simply doesn’t add up, she said. “The state likes to say ‘razor-thin’ profit margins. There’s no profit!”

The government does provide financial support for both parents and providers. In North Carolina, two salary subsidy programs paid around 5,100 preschool teachers an average of roughly $2,400 in the 2020-21 academic year, according to the Child Care Services Association. A college scholarship helps teachers earn degrees. And the state is giving out $805 million from federal COVID relief for centers to cover anything from rent to payroll software to antiseptic to mental health assistance for children or staff.

On the parent side, NC’s lauded Pre-K program is free for qualified families — if they can find a spot — though it covers only school hours, not the full work day, and it’s only for 4 year olds. Beyond that, the state offers subsidies for low-income families.

Unfortunately, subsidies don’t go far enough for either parents or centers, Chappel of the Child Care Services Association said. It “doesn’t cover the cost of quality.” For that matter, subsidies are mostly for lower-income parents, but “most families need help paying the cost of quality.”

The federal Build Back Better bill proposes $380 billion to cover free preschool for all 3- and 4-year-old children, cap child care costs at 7% of a family’s income and raise wages for workers. However, states would have to opt in, and of course the highly debated bill would have to pass with those provisions intact.

Build Back Better: Biden's child, elder care proposals come with a hefty price tag. But can they transform the industry?

So, how do child care workers manage? Some don’t, and leave the profession, as they are doing now. Some rely on family — Woods didn't take a paycheck for more than a year after starting Genesis. Some use public assistance: Section 8, food stamps — even, ironically, child care subsidies.

And some work second jobs.

'To live and not just to exist'

The sky Greensboro-ward was rosy as Rowell drove the few miles to Culp Fabric and parked by the loading dock. She walked through the wood-paneled entryway to a supply closet and got out a mop and a wheeled bucket. After a full day caring for children, she had another two or three hours to go cleaning the manufacturing company’s offices. The evening cleaning job pays $650 per month, enough extra “to live and not just to exist,” she said.

She cut through the warehouse, stacked high with rolls of heavy fabric. It makes her think of her dad, who used to work at a plant like this. “I just think how they start with the threads and turn them into this beautiful pieces, ship them everywhere.”

Rowell is used to the long hours. After work, she’ll eat something and relax, maybe watch Family Feud or window-shop on Facebook Marketplace. Her grown son plans to move out in April, but she can’t imagine having an empty nest. “Somebody’s always in need of a place and I open my doors,” she said.

She likes that her schedule fits all her work into five days, so she can spend the weekend with family, taking her mother out on a scenic drive, going to church, maybe bowling.

“This is not hard,” she said. “I can’t complain about it!” Moreover, said the woman who’d just spent a day with 4-year-olds, “There’s a lot of walking here. That’s a good thing. Get some exercise.”

Rowell probably wouldn’t complain if her feet caught on fire. But when asked to imagine that her child care job paid enough that she wouldn’t need a second job, she said, “Well, now that would be nice!”

Danielle Dreilinger is a North Carolina storytelling reporter and author of the book The Secret History of Home Economics. She went to Woodlands preschool in New York state. Contact her at 919-236-3141 or ddreilinger@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Times-News: Wage crisis in North Carolina child care drives workforce shortage