NC has long been hostile to unions, but labor may be on the rise | Opinion

When negotiations between the United Auto Workers and Daimler Truck involving thousands of workers in North Carolina came down to a midnight strike deadline last Friday, the company agreed to the union’s demands.

The results are a boon for workers at the Mercedes-Benz owned company that manufactures trucks, school buses and parts at plants that include locations in Gastonia, High Point and Mount Holly. The deal will give workers at least a 25% pay increase over four years, including a 10% raise immediately.

But what is more remarkable than the workers’ gains is how and where they came about – a union negotiation covering workers in North Carolina, the nation’s second-least unionized state.

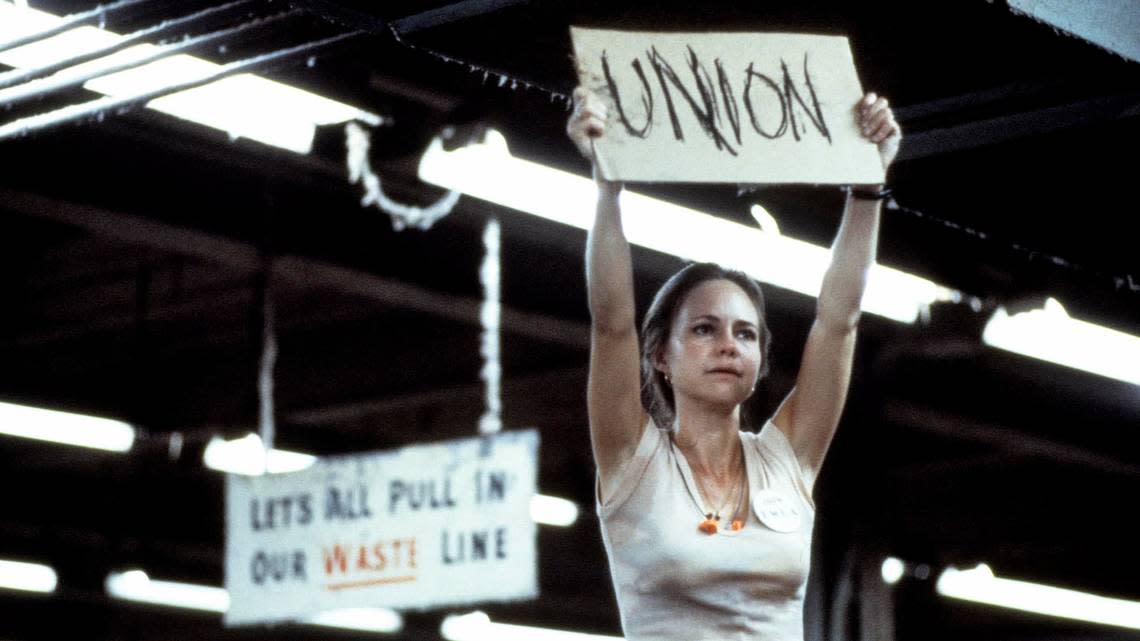

Could it be that the land of Norma Rae is becoming hospitable for organized labor?

Surely there are signs of a rising movement in the South. Workers at a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tenn., overwhelmingly approved joining the United Auto Workers (UAW) in April. It was the first southern auto plant to vote to unionize since the 1940s. Next up is a vote by thousands of workers at a Mercedes-Benz auto plant in Alabama.

“Working people are standing up and saying, ‘No more,’” MaryBe McMillan, president of the North Carolina State AFL-CIO, said in a Reuters report on a workers rally. ”No more moving companies South to bust unions and pay workers pennies. It is a new day here in the South.”

There is something stirring in North Carolina. Cornell University’s labor action tracker shows dozens of actions in North Carolina since 2021. The News & Observer reports that union campaigns have begun at Transcontinental Matthews near Charlotte and at 10 Roads Express in Greensboro. Even public workers – Wake County schools employees – staged a “walk-in” last week to demand pay raises.

Unions are on the rise in North Carolina, a right-to-work state that limits the power of unions and bans public employees from collective bargaining. But labor experts say there’s a long way to go before unions exert widespread pressure to increase wages and improve work conditions.

John Quinterno, a consultant and Duke visiting professor who studies workforce patterns in North Carolina, said more union activity counters North Carolina’s history as a source of low-wage labor.

“I think that model is under some pressure,” he said. “We’ve seen an increase in union sympathy and activity since the pandemic.”

But, he said, workers seeking to unionize still face “restrictions and strong headwinds” from public policy and companies.

Harry Katz, a professor of collective bargaining at Cornell University’s School of Industrial & Labor Relations, said a tight labor market and a positive view of unions among younger people is leading more Southern workers to unionize, but the movement is still faint.

“I don’t think we’re in the early stages of a revolution,” he said. “I wouldn’t overplay how much of a change is actually occurring.”

The willingness of foreign-owned auto and truck manufacturers to accept unions may reflect their concern about upsetting their unions back home, Katz said. When it comes to U.S. companies in the South, he said, “I think the resistance will be much more.”

Still, there is a significant change occurring in the public’s view of unions.

“The most important thing in the last 10 years is a more favorable outlook toward unions. They have a very high favorability among younger people,” he said. “Yet it remains to be seen how much difference that makes.”

It surely made a difference for more than 7,000 Diamler workers. That result will be noticed beyond the auto industry.

After a long history of policies that favored business owners in North Carolina, there’s a rising possibility that more workers in a tight labor market will exert their leverage to demand better working conditions.

At the table – instead of standing on it – a new generation of Norma Raes may yet be heard.

Associate opinion editor Ned Barnett can be reached at 919-404-7583, or nbarnett@ newsobserver.com.