For Native Americans in South Dakota, Thanksgiving is complicated. Here's what some had to say about the holiday

After a year-long hiatus from Thanksgiving because of COVID-19, Americans across the country are looking forward to a more normal celebration with their families and loved ones this year.

But the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted Native American communities last year, especially elders critical to keeping Native language and history alive. Because of that, many Native families who normally celebrate the holiday had smaller gatherings and stayed home.

The Argus Leader asked Native Americans from the Flandreau, Rosebud and the Oglala Lakota tribes about Thanksgiving and what it means to their communities as they head into a second winter of the pandemic and as South Dakota politicians and education leaders continue to debate how to handle Native American history in schools going forward.

More: DOE seeks applicants for second social studies standards revision workgroup

Francis Wakeman III: "From the textbook standpoint, we see pictures of Native people welcoming colonists"

Francis Wakeman III, 49, opened the Hunkake Cafe in Flandreau two years ago, serving food inspired by his grandparents' culinary traditions. When he thinks of Thanksgiving, the first thing that pops in his head is what he learned from textbooks.

"From a textbook standpoint, we see pictures of Native people welcoming colonists into this hemisphere over turkey and pumpkins," Wakeman said.

More: ACLU argues Noem, DOE 'likely' break laws by removing Oceti Sakowin from social studies standards

But Wakeman says the holiday is more of reaching out to people, and charity types of giving.

"In Dakota culture, we did things when people were born and when they died," Wakeman said. "That's where the food and gathering comes in and is really important, because it's a part of our history and our culture."

Nick Tilsen: "It erased the truth."

Nick Tilsen, 39, was born on the Pine Ridge Reservation and grew up going back and forth between the Twin Cities and the reservation. A citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation and current CEO of NDN Collective, an Indigenous-led nonprofit based in Rapid City, Tilsen learned Native history through his family as a child.

His parents met in 1973 during the midst of the Wounded Knee movement, when Native American activists of the American Indian Movement (AIM) occupied the town of Wounded Knee for 71 days.

"I grew up understanding Thanksgiving as an epic lie," said Tilsen. "The history books basically created a fake Americanized hallmark holiday that erased the truth of Native people."

More: Educators address legislative future of Indigenous inclusion, resilience in South Dakota schools

Tilsen explained just like any holiday in modern times when people are off work or school, Native Americans use Thanksgiving to convene with family. The truth about the story of Thanksgiving, or what he labels "Thanks-taking," that still resonates is Native people welcoming pilgrim settlers.

"We're hospitable people, it's part of our nature of who we are as people," said Tilsen. "For that to be weaponized against us, and then murdering of the same people who reached the hand to help you... that's what seems to be forgotten."

Pamela Byrd: "It's a sort of sweet and bitterness"

Pamela Byrd, 68, and an elder living on the Flandreau Reservation, spent last Thanksgiving over TV dinners and phone calls during the COVID-19 pandemic. Born in Arizona, Byrd has roots in the Hopi and Sioux tribes.

This year, she's looking forward to celebrating Thanksgiving at her niece's home in Sioux Falls. Byrd says Thanksgiving is a time to be with family, remember family members who have passed and have a good laugh.

More: Oceti Sakowin March for Our Children demands Indigenous history education for all of South Dakota

"It's a sort of sweet and bitterness," said Byrd. "I'm thankful for being thought of seven generations before and what was sacrificed for us, and we're still here."

Byrd will imagine her parents, who have passed, when she sits at the dinner table this Thanksgiving.

"My dad said, 'You have to laugh while you cry,'" she said. "So I remember good things about my dad, and wacky things about family members."

Garrie Kills A Hundred: "Thanksgiving is just another day"

Garrie Kills A Hundred, 67, recounts growing up in the most impoverished county in South Dakota, now known as Oglala Lakota. Thanksgiving was a time where the community would donate food, cook and make sure families who didn't have enough to eat had a good feast on the holiday, he said.

The holiday was just another day for Kills A Hundred, but for elders it was a time to get together.

More: Less than half of South Dakota's teachers using Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings

"You watch TV and you always here them say you should live Thanksgiving just like it was every day and have that spirit," he said. "That's a good thought, but back on Red Shirt Table when we would all get together, everybody would care for every family... we made sure every family had enough."

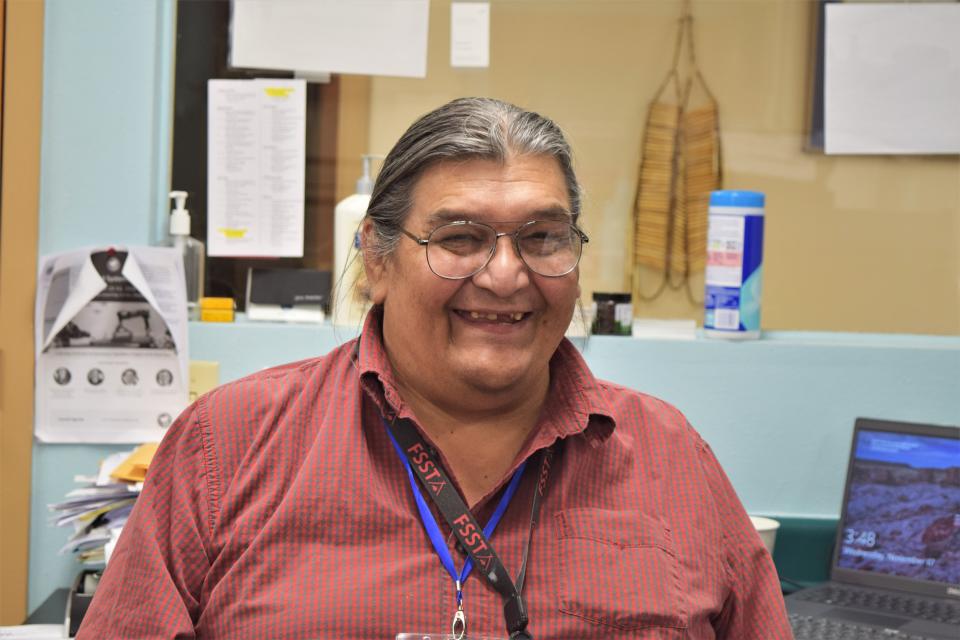

Duane Hollow Horn Bear: "It's not history."

Duane Hollow Horn Bear, 72, says Thanksgiving is less about the history and more about gratitude. The holiday has lost some of its roots in Native history because Native people have been acculturated and assimilated around American holidays, and also don't know their own history, culture and traditions, he said.

Hollow Horn Bear grew up on the Rosebud Reservation and was one of many Native American children forced into Catholic boarding schools in the '50s and '60s. Now, working as a Lakota language teacher at St. Francis Indian School in St. Francis, he believes bringing Native American history back needs to be done through changing South Dakota's social studies standards.

"In a cultural sense, it's what do we have that we are thankful for," Hollow Horn Bear said. "My life is filled with broken promises. I hardly dream anymore, because I'm struggling to survive. What we do give thanks for is our families, and the little things like this... It's not the history."

Email human rights reporter Nicole Ki at nki@argusleader.com or follow on Twitter at @_nicoleki.

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: Native Americans remember ancestors, give thanks on Thanksgiving 2021