Nasa Perseverance rover prepares for 'seven minutes of terror' in search for ancient life on Mars

Nasa is on tenterhooks as its Perseverance rover prepares to go through "seven minutes of terror" which will see it attempt the most treacherous landing yet on Mars.

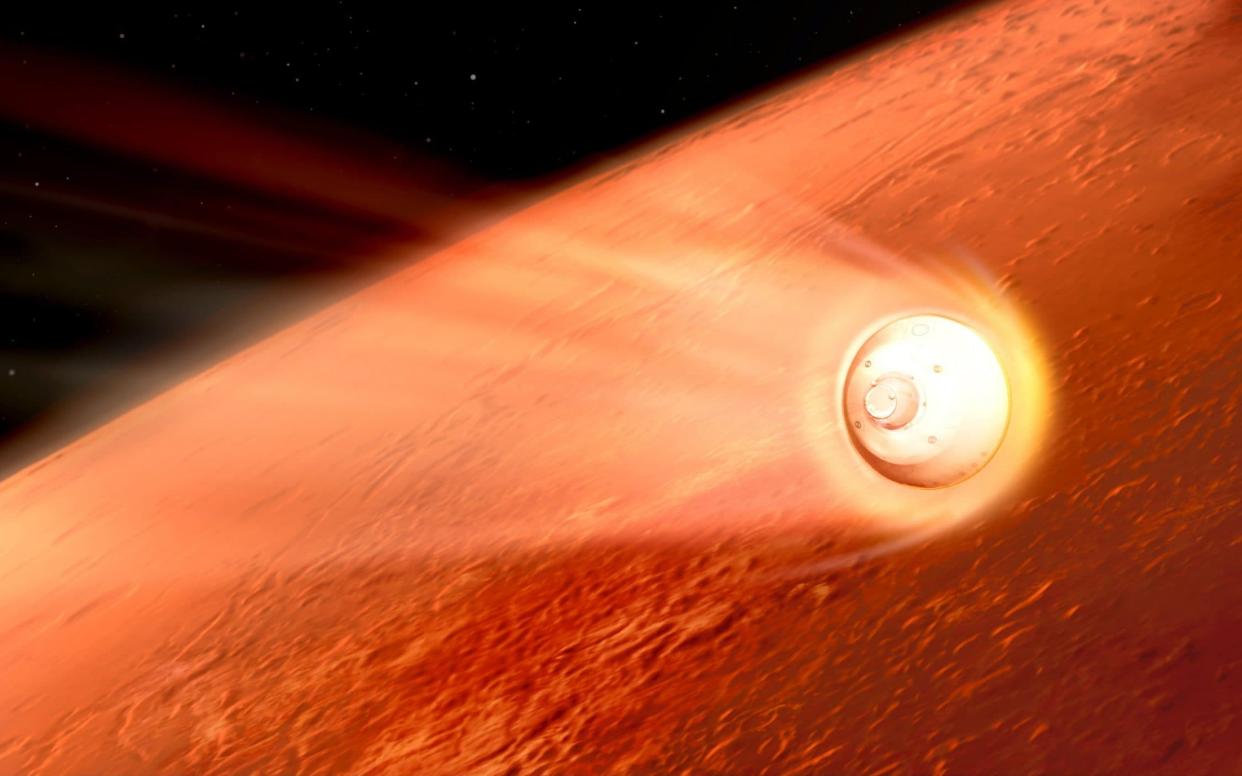

Perseverance will streak across the Martian sky at 12,000mph - more than six times as fast as a speeding bullet - before slowing itself down by deploying a 70ft wide parachute, and setting down in a crater littered with boulders.

If all goes according to plan the car-sized rover will reach the surface on Thursday at around 3.55pm US Eastern time.

It will be the culmination of the $2.7 billion Mars 2020 mission which took seven months to complete the 293 million mile journey.

'Seven minutes of terror'

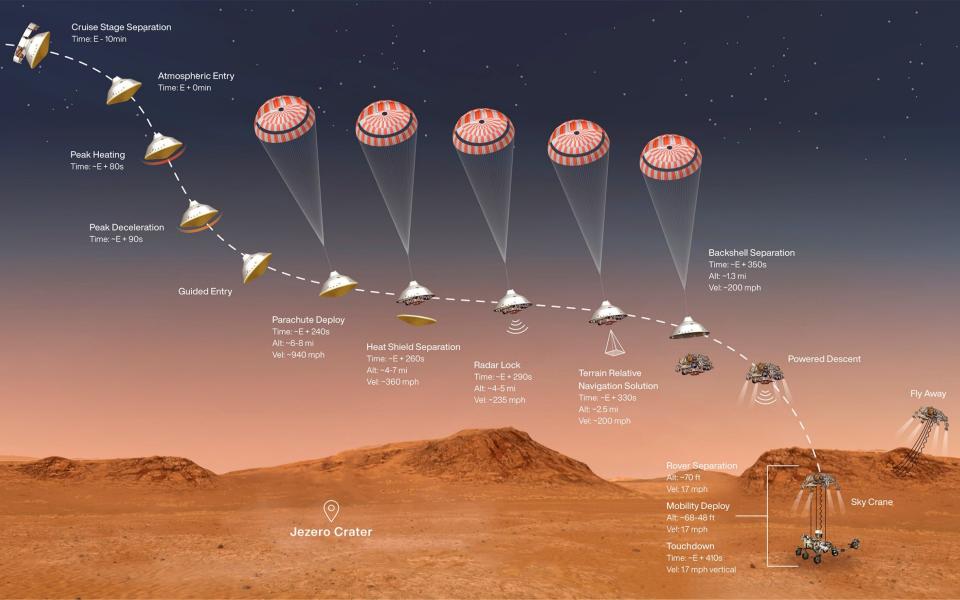

The entry, descent and landing [EDL] phase is known as the "seven minutes of terror".

Nasa scientists won't know what's happening in real time because it takes so long for radio signals to reach Earth.

Perseverance will send a radio alert as it begins the descent.

If they don't get another one seven minutes later then it means the rover crashed.

It will blast into the Martian atmosphere at 12,000mph encased in a protective capsule.

The giant parachute will then deploy to slow the descent capsule's plunge.

Scientists fear the violence of the parachute opening could mean it shreds into "confetti".

The heat shield will then fall away to release a jet-propelled "sky crane" hovercraft with the rover attached to its belly.

Once the parachute is jettisoned the sky crane's jet thrusters are set to immediately fire, slowing its descent to walking speed as it nears the surface.

It will then self-navigate to a smooth landing site, steering clear of boulders, cliffs and sand dunes.

Hovering over the surface the sky crane will lower Perseverance on nylon tethers, severing them when the rover's wheels reach the surface.

The sky crane will then fly off to crash a safe distance away.

Al Chen, head of the descent and landing team, said: "Success is never assured. And that's especially true when we're trying to land the biggest, heaviest and most complicated rover we've ever built to the most dangerous site we've ever attempted to land at."

Where will Perseverance land?

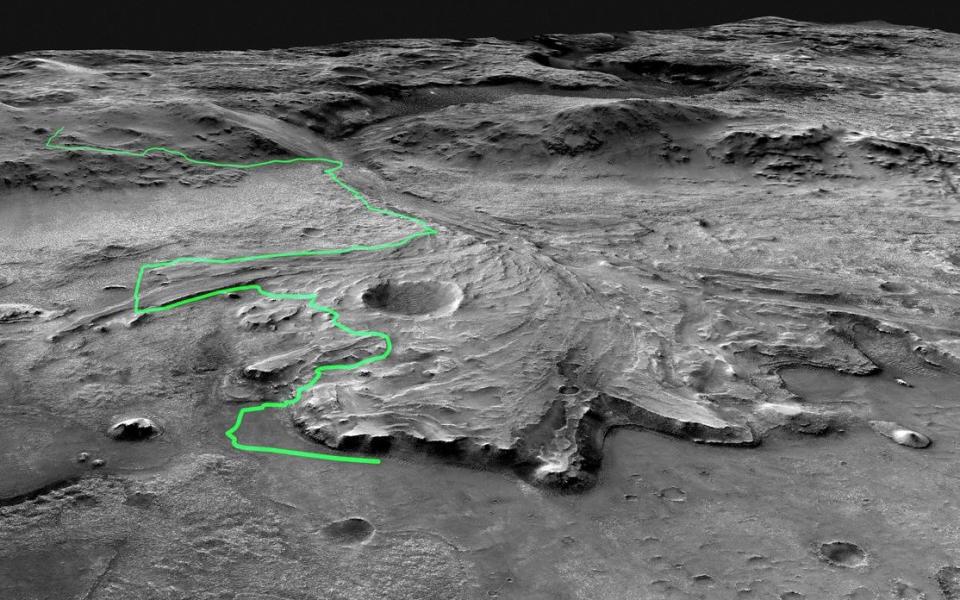

It will touch down in the potentially treacherous Jezero crater, which is filled with boulders.

The 28-mile wide crater was chosen because, three billion years ago, it was home to a river delta, and Perseverance will search for signs of ancient microbial life.

Scientists believe it may harbour a rich trove of fossilised microorganisms.

Nasa scientist Ken Farley said during this period Mars was "very similar to Earth in several important ways."

He said: "It had a substantial atmosphere, it had lakes and rivers on its surface, and it had habitable environments, places where organisms that we know about on Earth today could have thrived."

However, the crater's rugged terrain, deeply carved by ancient flows of liquid water, makes it treacherous as a landing zone.

If it lands successfully Perseverance will drill out half-ounce rock samples which Nasa ultimately hopes to bring back to Earth a decade from now on a later mission.

Why is Perseverance special?

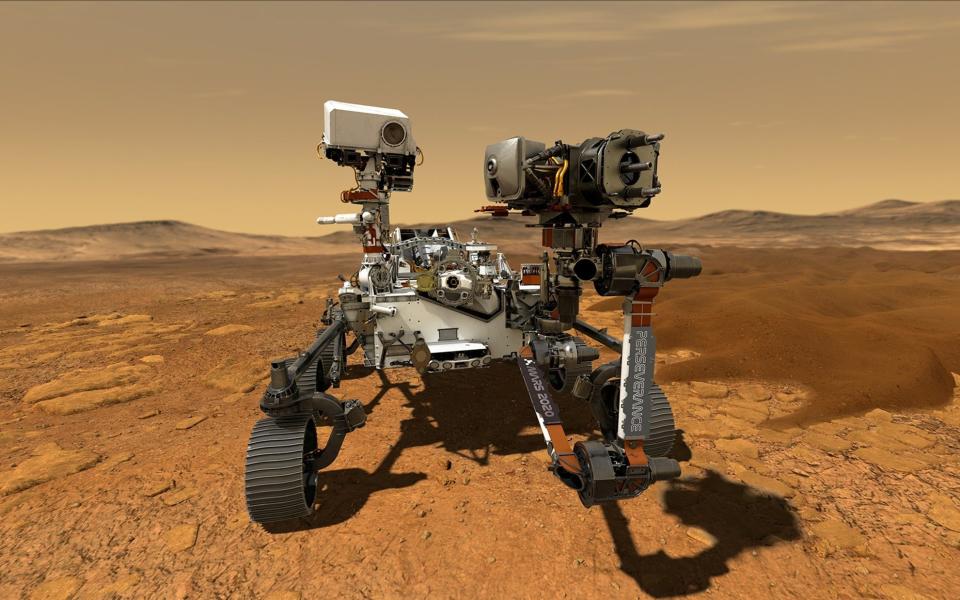

The six-wheel, nuclear battery-powered rover is the largest ever vehicle to be dispatched to the Red Planet.

Nasa scientists have described their challenge as "landing a car on Mars".

Built at the space agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory it weighs a ton and has a robotic arm that's 7ft long.

It also has 19 cameras, and two microphones to record the Martian soundscape.

The cameras mean Perseverance will be able to film its own landing, and the microphones mean people on Earth will be able to hear muffled sounds from Mars.

Low resolution photos of the surface will arrive quickly.

Video footage, including entry into the atmosphere, is expected later.

Lori Glaze, of Nasa's planetary science division, said: "We're going to be able to watch ourselves land for the first time on another planet."

If it arrives intact Perseverance will be only the fifth rover to do so. All have been American.

Its top speed is 152 meters per hour (about 0.1mph) which is faster than any of its predecessors.

Over several years Perseverance will collect and store up to 30 rock and soil samples in cigar-sized tubes.

Nasa aims to eventually return the samples to Earth on a future mission in the 2030s.

Mr Farley said: "The scientists who will analyse these samples are in school today. They might not even be born yet."

The Perseverance mission will also test a system that can convert oxygen from Mars' primarily carbon dioxide atmosphere.

The Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE) will used electrolysis to produce small amounts of oxygen.

A helicopter on Mars

As part of the mission Nasa wants to fly, for the first time, a powered aircraft on another planet.

The mini-helicopter, called Ingenuity, will attempt to fly in an atmosphere one per cent the density of Earth's.

Ingenuity weighs just four pounds and its carbon-fiber blades will spin at a dizzying 2,400 revolutions per minute.

It has has four feet, a box-like body and two cameras.

The machine is also equipped with solar cells to recharge its batteries.

It will arrive attached to the underside of Perseverance, which will drop it to the ground once it has landed then drive away.

Up to five flights are planned over a period of a month.

Ingenuity will fly at altitudes of up to 15ft and for distances of up to 160ft, and each flight will last up to 90 seconds.

It is too far away to be controlled from Earth and is therefore designed to fly autonomously.

Bob Balaram, Ingenuity's chief engineer, said: "It basically opens up a whole new dimension of exploring Mars."

Space race 2.0

The arrival of the Nasa lander is part of an extraordinary confluence of interplanetary missions unprecedented in the history of spacefaring.

Probes sent by China and the UAE have already arrived in the past week. All three Mars missions launched last July to take advantage of the planet's close alignment to Earth that occurs only every two years.

Rival mission Hope from the UAE became the first to Mars' orbit on February 9, while China's Tianwen-1 probe sent back its first images of Mars on February 6 before entering orbit on the 10th.

Unlike the other two Mars ventures, China's Tianwen-1 and Mars 2020 from the United States, the UAE's probe will not land on the Red Planet.

While the probe is designed to provide a comprehensive image of the planet's weather dynamics, it is also a step towards a much more ambitious goal - building a human settlement on Mars within 100 years.

"It's not about reaching Mars, it's a tool for a much bigger objective. The government wanted to see a big shift in the mindset of Emirati youth... to expedite the creation of an advanced science and technology sector in the UAE," Omran Sharaf, the mission's project manager, said.

Tianwen-1 is China's second attempt to send a spacecraft to Mars. In 2011, a Chinese orbiter that was part of a Russian mission did not make it out of Earth orbit.

China's secretive, military-linked space program has progressed considerably since then. In December, its Change's 5 mission was the first to bring lunar rocks to Earth since the 1970s. China was also the first country to land a spacecraft on the little-explored far side of the moon in 2019.

Tianwen, the title of an ancient poem, means "Quest for Heavenly Truth."

The mission is China's most ambitious yet. If all goes as planned, the rover would separate from the spacecraft and attempt to touch down, likely in May. China would become only the second nation to do so successfully.

Landing a spacecraft on Martian soil is notoriously difficult, and China's attempt will involve a parachute, back-firing rockets and airbags. Its proposed landing site is inside the massive, rock-strewn, Utopia Planitia, where the US Viking 2 lander touched down in 1976.

The solar-powered rover, about the size of a golf cart, is expected to operate for about three months, and the orbiter for two years.