Is NASA Actually Working On a Warp Drive?

A NASA propulsion physicist has, he says, resolved a paradox in a hypothetical warp drive.

The Alcubierre drive uses a huge amount of energy to make a sort of fold-like pocket dimension.

The NASA paper suggests a rolling start in order to guarantee a travel direction.

Is NASA really working on . . . a warp drive? An internal feasibility report suggests the agency might be, or at least that the idea of traveling through folded space is part of the NASA interstellar spaceflight menu.

In the report, advanced propulsion physicist Harold “Sonny” White explains the ideas of theoretical physicist (and peer) Miguel Alcubierre. He then describes a “paradox” in Alcubierre’s work, and how that paradox might be resolved to make a working model.

The colloquial term “warp drive” has come from science fiction, and it refers to the idea of sub-luminal (less than the speed of light) travel that conforms to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, but still pushes speed to absolute maximum that’s theoretically possible. In the Star Trek canon, progressive designs come closer and closer to a hypothetical barrier—the way real scientists continue to hew closer and closer to absolute zero. In real life, light speed is the barrier.

The Alcubierre drive works like a physics version of a classic party trick. The spaceship sits in spacetime while science pulls the fabric from in front of it to behind it, like a tablecloth pulled out from under a full spread of dishes. White explains:

“The concept of operations as described by Alcubierre is that the spacecraft would depart the point of origin (e.g. earth) using some conventional propulsion system and travel a distance d, then bring the craft to a stop relative to the departure point. The field would be turned on and the craft would zip off to its stellar destination, never locally breaking the speed of light, but covering the distance in an arbitrarily short period of time just the same.”

Alcubierre’s theory dates to 1994, and physicists have used it as a jumping-off point for further discussion ever since. By creating a kind of pocket world where a spaceship can operate seemingly outside of physics, the laws of physics can be sidestepped—or so the theory goes.

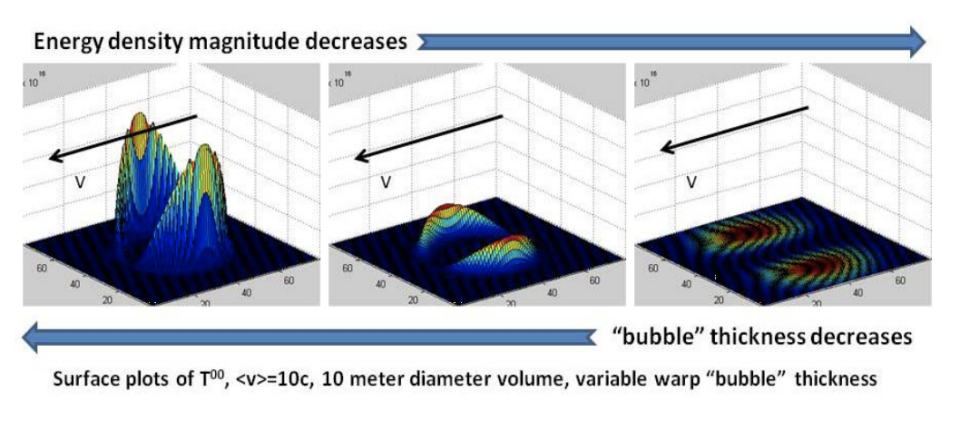

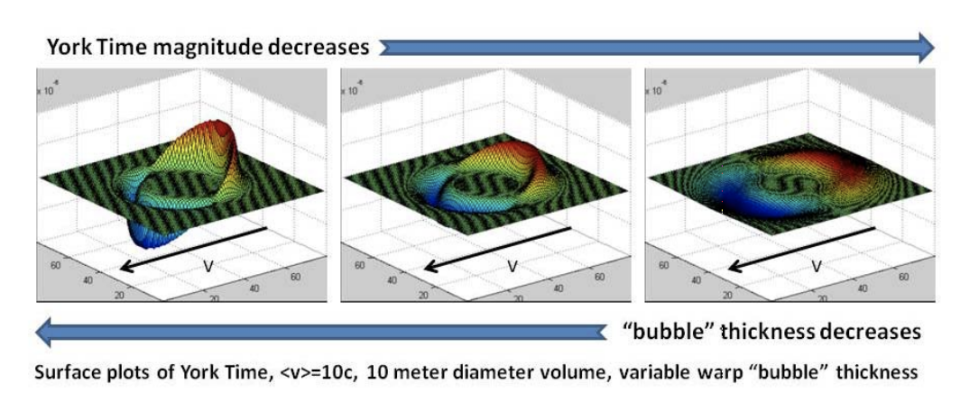

What’s the paradox? White describes it this way: “When the energy density is initiated, the choice in direction of the +x-axis is mathematically arbitrary, so how does the spacecraft ‘know’ which direction to go?” Sci-fi has solved this paradox by inventing a “stable wormhole,” but White can’t fly a deus ex machina to Alpha Centauri.

Instead, he suggests a slightly different paradigm: “In this modified concept of operations, the spacecraft departs earth and establishes an initial sub-luminal velocity, then initiates the field. When active, the field’s boost acts on the initial velocity as a scalar multiplier resulting in a much higher apparent speed,” White explains.

Instead of coming to a stop and then engaging the warp drive, the ship would use a rolling start as a directional cue.

We think of warp speed as, well, the only way faraway interstellar travel will ever be feasible. And White has focused on one mathematical paradox within the work, but that’s not the only such obstacle.

He suggests the proving ground for warp speed could be, well, closer to home. “[T]he idea of a warp drive may have some fruitful domestic applications ‘subliminally,’ allowing it to be matured before it is engaged as a true interstellar drive system,” he explains.

If scientists can make the so-called “negative mass” required for an Alcubierre drive, even a tiny example could be deployed within Earth’s atmosphere.

You Might Also Like