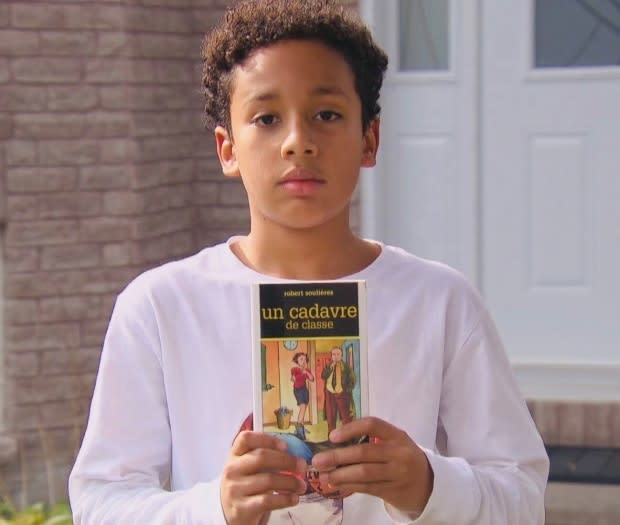

N-word in son's school book prompts rights complaint from Gatineau, Que., dad

A father in Gatineau, Que., has filed a human rights complaint after his son was assigned to read a book containing the N-word in elementary school.

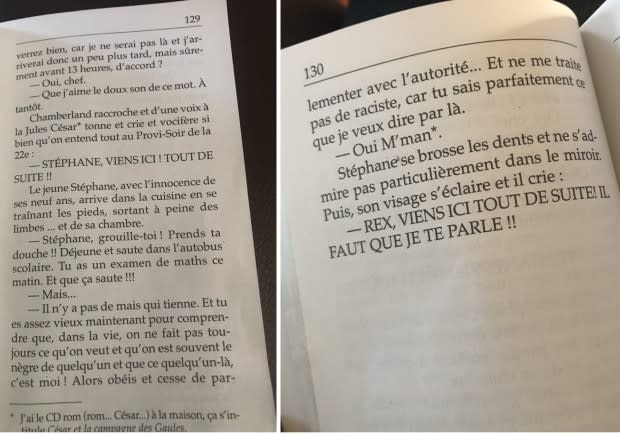

The book, Un Cadavre de Classe by Robert Soulières, was first published in 1997 and is part of a mystery series for children. On page 129, there's an exchange between a mother and son that reads:

"Et tu es assez vieux maintenant pour comprendre que, dans la vie, on ne fait pas toujours ce qu'on veut et qu'on est souvent le nègre de quelqu'un et que ce quelqu'un-là, c'est moi!"

In English that translates to:

"And you're old enough now to understand that in life we do not always do what we want and that we are often someone's Negro, and that someone is me."

In French, the word Nègre can mean both Negro and the N-word.

"I was shocked," Gioberti Francois said.

Francois said his son Quincy, 12, was reading the book in the back seat of their car in May as they were returning from a trip to Montreal. Quincy, who at the time was attending Ècoles des Cavaliers in Gatineau's Aylmer sector, was reading aloud when Francois heard the offensive word.

"I actually stopped the car to read it," he said.

Complained to school, board, ministry

The passage continues on page 130 to read:

"Alors obéis et cesse de parlementer avec l'autorité ... Et ne me traite pas de raciste, car tu sais parfaitement ce que je veux dire par là."

That translates to:

"So obey and stop arguing with authority ... And don't accuse me of being racist, because you know exactly what I mean by that."

But "racist" is exactly what Francois thought the phrase was, prompting him to write a letter to the school, the school board, the ministry of education and eventually, Quebec's human rights commission.

"Sometimes we live with ... [a] relic of the past," Francois said. "And sometimes it's a movement, like what I'm doing, that will allow us to remove this in our society."

The local public school board, Commission Scolaire des Portages-de-l'Outaouais (CSPO), said Quincy's former school stopped using the book at the end of the 2018-2019 school year, but it could not confirm whether students at other schools within the board were still reading it.

Racist history

The board said the book was used as an educational tool to help children identify difficult vocabulary and highlight societal issues, including racism. The book was chosen, the board said, to educate young people about the issue.

But Francois said his son read the passage without an understanding of what the word Nègre meant, or its racist history.

"He wasn't aware of that," Francois said.

"So ... we talked about systemic racism, black history and what effect [that word] could have on our society as a whole."

The children's book is endorsed by Quebec's Education Ministry and remains on its Open Books website. In an emailed statement to CBC News, the ministry said it's looking into the issue.

Not the 1st time

In 2010, the word Nègre landed French parfumier Jean-Paul Guerlain in hot water.

He was found guilty of racial slander and ordered to pay €6,000 after remarking during a television interview that he had worked like a "Nègre" to create one of his company's scents, according to Agence France Presse.

Guerlain later apologized, saying he was from a different generation when the expression was common.

The Liberal MP for Hull–Aylmer, Greg Fergus, said he considers the word to be offensive and believes it should go the way of other historic phrases that employ prejudiced notions about minorities.

"If you use those kind of phrases, what does that make you think of the people who belong to those groups? If you are Jewish, if you are Roma or if you're black," said Fergus, who is black.

Fergus said it's important for teachers and educators to talk openly about why words like Nègre are offensive if students are to understand why they're hurtful.

"We can't completely sanitize our history and culture and nor should we," he said.

"But what we should do is have a conversation around it. Why was that word being used? What is the subtext? What is the context in which it's being used?"

Francois said his human rights complaint is in part about creating an opportunity for learning and growth.

"We can complain, we can fight about this, but at the end of the day, what we want for our children is a better world."