N.B. decides against updates to Clean Air Act to improve indoor air quality

Nearly a year after the legislature unanimously passed an Opposition motion to update the New Brunswick Clean Air Act and improve air quality in public buildings to reduce the spread of airborne illnesses, such as COVID-19, the government says it won't update the act after all.

The Department of Environment and Local Government reviewed the act, which dates back to 1997, and "determined updating was not necessary because protections already exist under other legislation," such as the Occupational Health and Safety Act, said spokesperson Clarissa Andersen.

Liberal Leader Susan Holt, who learned of the decision from CBC News, called it "disappointing, but not surprising."

"That they've determined it's not necessary for an act that is old, out of date, does not apply the most recent standards that experts in air quality suggest? Well, it validates what we thought, that this government doesn't care about clean air," she said.

An infection control epidemiologist called the decision "naive."

"I couldn't imagine a worse time for any government to say, 'Wow, we don't need to do anything more about indoor air because we have this covered,'" said Colin Furness, who's an associate professor at the University of Toronto.

"That can't be. It just can't be," he said. "We have learned too much over the last few years about what safe indoor air is to be able to make naive statements like that."

Sought to protect students, patients, seniors

Motion 36, tabled in April by Liberal MLA Gilles LePage, Opposition critic on the environment, urged the government to "modernize New Brunswick's air quality laws and standards with a goal of bringing forward a strengthened Clean Air Act and modernized regulations."

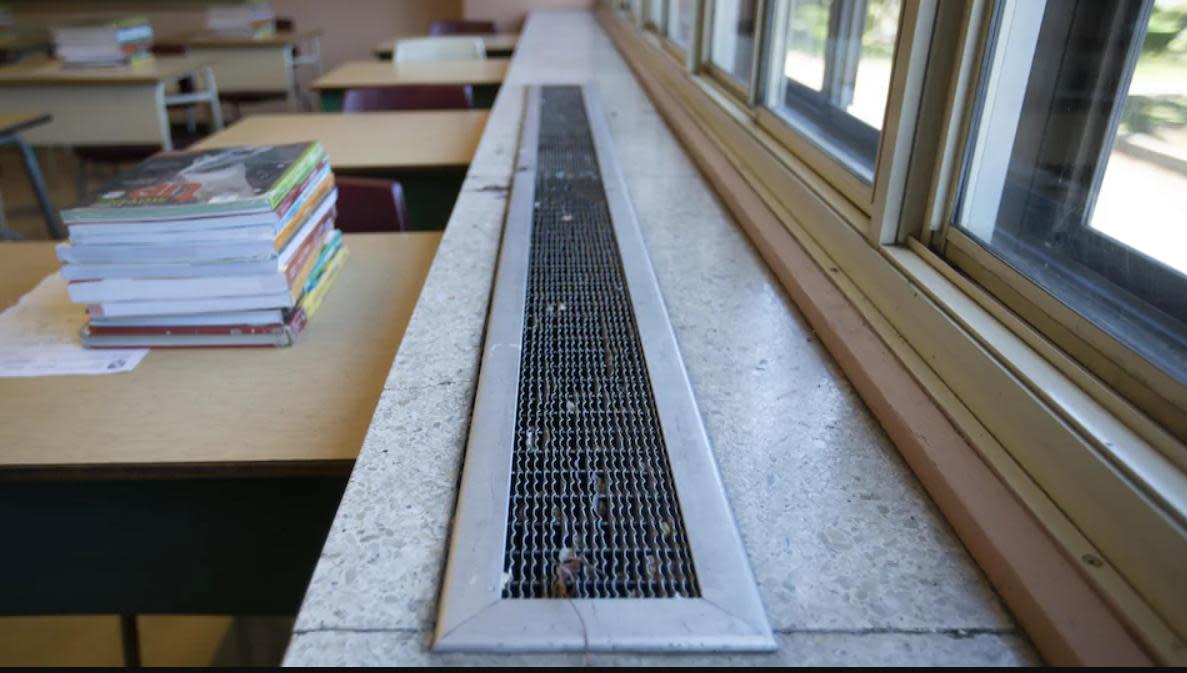

It also called on the government to "bring forward a plan to monitor, report, and improve air quality systems in public buildings like hospitals, schools, and government buildings to mitigate the risks associated with the transfer of airborne illnesses, airborne contaminants, and other harmful agents."

The government is not obligated to take action on Opposition motions.

Liberal Leader Susan Holt said a number of other Opposition motions have passed unanimously in the legislature over the past two years, but most have not been acted upon. (Radio-Canada)

Still, Liberal MLA and then-health critic Jean-Claude D'Amours was hopeful when the motion passed in June that the government would undertake an in-depth review of the act and implement new, higher standards, and invest in equipment, such as ventilation systems to help protect the health of students, hospital patients, seniors in long-term care homes and other New Brunswickers.

According to Holt, it was an "extremely well-supported motion."

"The amount of public engagement in the motion and the amount of people who reached out to their MLAs, to us, to say, 'This matters, we want you to support it' — It had the most public connection of anything we did in the House last year."

Act designed to target outdoor air quality

But the Department of Environment and Local Government spokesperson said the Clean Air Act was "purposefully designed to target the air quality in the environment," while indoor air is "principally a matter of ventilation and building design."

The Occupational Health and Safety Act "outlines exposure limits and guidelines for indoor air contaminants anywhere workers are present," Andersen said in an emailed statement.

This act is the responsibility of the Department of Post-Secondary, Education, Training and Labour, and it is administered by WorkSafeNB.

The Department of Post-Secondary, Education, Training and Labou did not immediately respond to a request for comment about what the department is doing or plans to do.

WorkSafeNB's jurisdiction, according to spokesperson Lynn Meahan-Carson, "only extends to the protections for air quality where workers are present and does not include the general public."

Asked about the other component of the motion, which called on the government to "monitor, report, and improve air quality systems" in public and government buildings, Andersen reiterated the department "determined that existing legislation, such as the Occupational Health and Safety Act, already provided a legislative tool to investigate and maintain safe air in public buildings."

Preventative measures protect health, strained system

Holt contends taking action now to modernize the Clean Air Act is important. "We have a health-care system that is strained to the max. Preventative measures to keep people healthy are important to our bottom line and to the health of our province."

She points to air quality test results from public schools in 2022-23. Twenty-nine of the 35 schools tested had peak carbon dioxide levels above the Department of Education's threshold of 1,500 parts per million (ppm) — a threshold some critics have argued is too high.

Nearly 83 per cent of tested schools exceeded peak CO2 limits in 2022-23, air quality results show. (Syda Productions/Shutterstock)

Carbon dioxide is used as a proxy to measure air quality and the rate at which air is being renewed, which can also serve as a warning sign about the risk of spread of COVID-19 and other respiratory illnesses, according to experts.

"So at a very minimum, I think we should make sure our schools are safe and healthy places to be" for students and teachers, said Holt.

"We can anticipate future airborne diseases. And if we want to be smart with our pennies, the best investments are preventative ones so that we can avoid the kind of deaths and negative impacts that we experienced through this [COVID-19] pandemic."

Indoor air tends to be 'a lot more dangerous' than outdoor air because it's where pollutants accumulate, said Colin Furness, an infection control epidemiologist. (Katarina Kuruc)

Furness said it's "very rare" to encounter pre-COVID legislation that "actually adequately reflects what we now know about indoor air and about really what we need to feel safe."

He notes the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, known as ASHRAE, issued new indoor air quality standards last summer, providing a "ready yardstick."

"It would be really surprising if many, or even any [New Brunswick buildings], are really up to that ideal standard," he said. "And that's unfortunate," not only as far as protecting people from infectious diseases, but also from particulate matter, such as wildfire smoke, which is harmful to the lungs.