How much can a president impact the economy?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

An earlier version of this article was published in the On the Trail 2024 newsletter. Sign up to receive the newsletter in your inbox on Tuesday and Friday mornings here. To submit a question to next week’s Friday Mailbag, email onthetrail@deseretnews.com.

Good morning, friends.

3 things to know

The prosecution rested in the hush money case against Donald Trump on Monday after Trump’s defense attorneys finished their cross-examination. During the final line of questions, former Trump attorney Michael Cohen admitted to stealing money from the Trump Organization, which he clarified during redirect by the prosecution. After the prosecution rested, Trump’s attorneys made a motion to dismiss the case, which the judge said he would review. Read more here.

Can Arizona Republicans stop fighting long enough to win? We’ll find out in November, when Arizona becomes ground zero for both the presidential election and a key U.S. Senate race. If Trump wins Arizona, he will likely win the presidency. The same goes for the race to replace retiring Sen. Kyrsten Sinema — if Republicans win, they’ll likely retake control of the Senate. But both would require Republicans to stop tearing each other apart. That doesn’t look likely. Read more here.

Biden blasted the International Criminal Court as “outrageous” on Monday after it sought an arrest warrant for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, as well as leaders of terrorist group Hamas. “There is no equivalence — none — between Israel and Hamas. We will always stand with Israel against threats to its security,” Biden said. The ongoing instability in the Middle East sharpened over the weekend when Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi was killed in a helicopter crash. Read more here.

The Big Idea

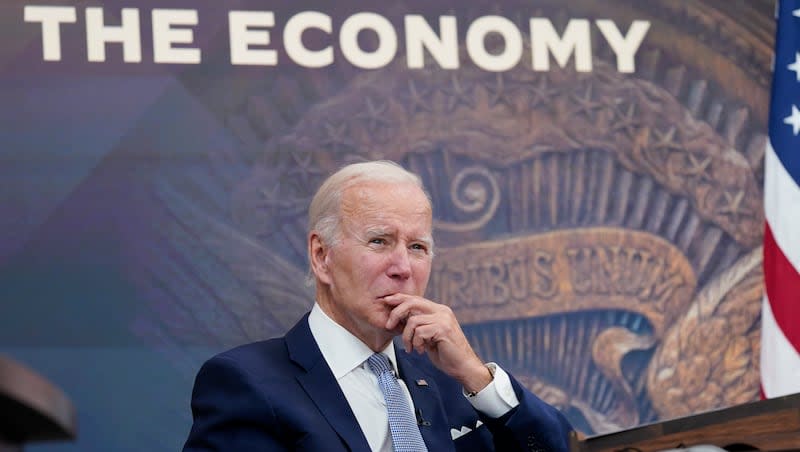

The great economic blame game

In Friday’s edition of On the Trail, I spoke with a Nevada pollster about the latest New York Times/Siena College poll. He shared some interesting insights about the speed at which Nevada — a reliably blue state for several election cycles — is now turning red, thanks to economic discontent with the Biden administration. (If you missed our conversation, you can read it here.)

When you parse the numbers in this latest Times poll, it becomes clear that the economy is a big deal beyond Nevada, too. A quarter of all voters surveyed say the economy (21%) and cost of living (7%) are the most important issues for them. More than half of voters say that the economy is “poor.” A big majority — 69% — of voters say the country’s political and economic system needs “major changes” or “to be torn down entirely.”

I’ve written before about the weakness of the president’s “Bidenomics” message, like here and here. Biden continues to try to sell voters on his administration’s economic accomplishments, like reducing inflation and bringing down unemployment after the pandemic. But voters aren’t buying it, due to a host of other reasons: inflation is still high, interest rates are high, average household net worth is low, average debt is high.

This disconnect — between Biden’s messaging and voters’ reactions — will be a central theme in the 2024 election. By many measures, Trump oversaw a flourishing domestic economy before the pandemic ravaged it. By like measure, Biden has navigated the U.S. through a largely successful economic recovery, though voters do not share his perspective.

That presents a paradox: voters are quick to say the national economy is in shambles, but they are much slower to critique their local economy. According to a Wall Street Journal poll, only a quarter of voters in swing states think the nation is heading in the right direction; only 36% consider the U.S. economy to currently be “excellent” or “good.”

But when you ask the same voters about their own states, they are much more complimentary. 64% of North Carolinians say their economy is excellent or good. 59% of Georgians say the same. 52% of Nevadans, too. Overall, 56% of swing-state voters have favorable views of their local economy — a full 20 percentage points higher than those who view the nation’s economy favorably. (Polls have repeatedly found the same local-national discrepancy: here’s Gallup from 2001 and 2012 showing the same.)

Why the disconnect? Are voters more willing to ascribe economic failures to the White House than to local factors? And what role does the president really play in the economy’s health? Whose fault is it?

I reached out to Michael Kofoed, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and a research fellow at the Institute of Labor Economics (and a Deseret News contributor), to break it down. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Samuel Benson: Voters seem quick to blame Biden (or Trump, during the pandemic) for the U.S. economy’s struggles. How large of a role do presidents really play?

Michael Kofoed: The American economy is extremely strong on fundamentals, regardless of who is in the White House. World events and trends are just going to play themselves out. For example, a lot of people are feeling the pain from COVID inflation. There were some things that the Biden administration did that absolutely contributed to it. But Americans also don’t like to think about the economy outside of the United States. Sometimes when I talk with relatives, I ask, “Did Biden cause the even higher inflation that happened in the Nordic countries during the last couple of years?” And they’re like, “Well, no, he couldn’t have caused that, too.”

The problem we have as consumers is it’s really hard for us to think about abstract forces moving the economy along. We want someone to give credit to; we want someone to blame. And so it’s very easy for us to blame the president, or give credit to the president.

SB: Aside from appointing officials to the Fed, are there any concrete ways that a sitting president can put his thumb on the economy?

MK: That’s a great question. The president chooses the Fed, but the Fed is off-cycle. So if Trump gets elected, he can’t just turn around and fire (Federal Reserve chair) Jerome Powell, because the Fed is usually appointed halfway through the president’s term. So even monetary policy is generally, in the short run, outside of the president’s purview.

Where the president does have some influence is on taxes and spending. If you think about the economy as an 18-wheeler, and it’s heading down the highway, how could we just steer a little bit back and forth? You could do that by either increasing government spending if you’re a Democrat, or cutting taxes if you’re a Republican. Those are the levers the two parties tend to pull. Again, the problem the president has is the person who actually has the most power on those two tools is the House of Representatives, because the president does not set the budget.

If you have divided government, then the good thing is that everyone’s checked, and so the blame and the credit should be equally shared. But that rarely ever happens. My favorite polling that political scientists do is when they ask your approval of Congress in general, and then they ask about your individual member of Congress. People often have a low view of Congress but an extremely high view of their own representative.

SB: There is similar polling about the economy, too. Voters have low views of the national economy but higher views of their state’s economy. Why is that?

MK: It is the way we act as humans. Behavioral economics shows that when something good happens to us, it’s something that I caused. But when something bad happens to us, it’s something someone else caused. For example, if inflation causes prices to go up, but then my firm gives me a cost of living adjustment at the end of the year. So, I’m like, “oh, prices went up — that’s someone else’s fault. But I got this cost of living adjustment — that’s because I was a good employee.” It’s just the way we view the world. I think when we put ourselves in our own media bubbles, it just makes that effect even worse.

People are telling us their finances are bad, but consumer spending is as high as it’s ever been right now. But I’ve learned from way too family barbecues that when people say, “I’m hurting,” and you say, “No, my data set over here says you’re not hurting,” they don’t ever wake up and say, “Oh, I’m not hurting.” So this is the precarious position the Biden administration finds itself in: the numbers are good, but people don’t feel it because of inflation. So if you say, “You all need to change the way you feel,” that’s never going to be a winning strategy.

SB: If you went to a barbecue with every American voter, what are the things you would tell them to pay attention to before November?

MK: First, remember that the most important thing is not the price of the object, but how much you have to work to buy that thing. What is your actual purchasing power? The other thing I would say as you’re going in to vote for president, is you want to make take a good, hard look at actual, real data. (The St. Louis Fed website is really good for this.) Say to yourself, “Is it my feelings that are most important here, or is it the actual behavior that I’m doing?”

I don’t think the president can cause wide swings in economic activity. I do think that the president has the ability to cause some swings in the short run. So if we’re going after things like international trade or causing an uncertain business climate, those are going to be the things that are going to hurt you in the short run that the president can have some influence over.

As economists, we’re like the Vulcans on “Star Trek,” telling people to not trust their feelings, which sounds really awful. But look at the data. Our eyes and our feelings will always trick us.

What I’m reading

Idaho has seen some of the country’s most sweeping abortion legislation. But this story — about a progressive activist and a Republican lawmaker who found common ground — suggests that there is still space for compromise on one of America’s most controversial issues. North Idaho Has Drifted to the Extreme Right. One Republican Thinks It’s Hit Its Limit. (Cassidy Randall, Politico Magazine)

Biden and Trump will debate, but not without fireworks: after the two camps agreed to a pair of debates last week, the Trump campaign then announced two additional debates and chided Biden for not accepting. The Biden campaign quickly declared an end to the “debates about debates.” But was it all a show? “The public posturing and macho gurgling was a bit of theater to mask the ugly truth: The campaigns had acted in a mature, pragmatic fashion with each other,” Chris Stirewalt writes. The Debate About the Debate About Debates (on The Dispatch’s sleek, new site)

Trump could go to prison. We’ll have more clarity on the unlikely-but-possible situation as soon as next week, when a jury is expected to huddle and deliberate over the ex-president’s alleged falsification of business records in a scheme to bury an affair with a porn star. Does that damage Trump’s electability? Depends on who you ask. Will Trump Run as a Felon? A Big 2024 Question Will Soon Be Answered. (Shane Goldmacher, The New York Times)

Tuesday trivia

Last Tuesday’s question: Only one presidential candidate in U.S. history both 1.) ran for president from jail, and 2.) was assassinated while running. Who was it?

Congrats to reader Jason Nelson for getting this one correct. (As well as nine others, but Jason was first.)

The answer: Joseph Smith, an 1844 candidate and founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Smith ran on the Reform Party ticket, a party which he created, and his platform included the abolition of slavery, economic reform and criminal justice reform. Smith was the first U.S. presidential candidate to be assassinated. Read more here.

This week’s question:

This fall, Republicans attempt to retake the Senate, while Democrats try to gain a majority in the House. When was the last time both the House and the Senate simultaneously changed hands in a presidential election year?

Think you know the answer? Drop me a line: onthetrail@deseretnews.com.

See you on the trail.

Editor’s Note: The Deseret News is committed to covering issues of substance in the 2024 presidential race from its unique perspective and editorial values. Our team of political reporters will bring you in-depth coverage of the most relevant news and information to help you make an informed decision. Find our complete coverage of the election here.