Most of my life I was silent about my sister’s murder and the death penalty. No more. | Opinion

Growing up, the one thing I never imagined was that I’d be a family member of a murder victim. But at age 19 that’s exactly what I became.

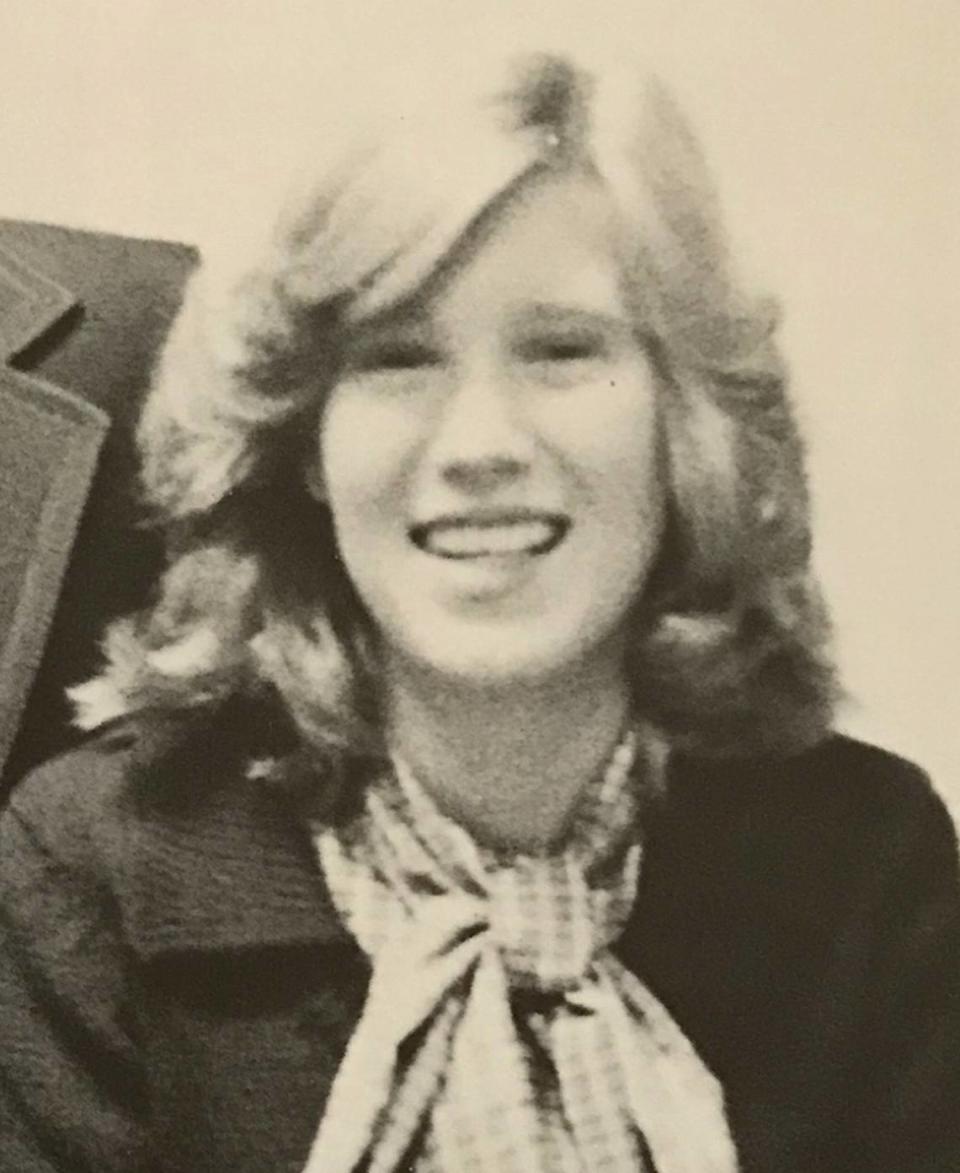

On Oct. 29, 1977, my younger sister, Carlotta Hartness, and her classmate, Tommy Taylor, were randomly murdered by three men. It was all over the TV news and in the newspapers. Murders were rare back then.

Two of the men plead guilty to the murders and were eventually executed, in 1985 and 1986. The executions were gargantuan news in South Carolina. Even Mother Teresa tried to intervene. The third killer, who testified against the others, died in prison in 2003.

Carlotta had just turned 14. She and Tommy, 17, went to a park in northeast Columbia — and they never came home. We learned later that Tommy had been shot in front of Carlotta and that Carlotta had been kidnapped, tortured, raped and murdered. Her body was found days later.

After Carlotta’s murder, the trauma of losing her consumed my entire being. It took everything we had for my family and me to survive the new reality. Today, 46 years later, hardly a day goes by that I don’t think about the violence and terror my sister experienced — and the enduring impact on my family. I’ve witnessed the ripple effects of my sister’s murder on my own children.

For most of my life, I remained silent about this experience. I tried to push it away. Then, six years ago, I saw a graphic of handguns that depicted the victims as “stick-figures.” I can assure you there are no stick figures in murder.

At this point, I no longer cared how uncomfortable my family’s story made people feel. Each murder victim family member has a story that deserves to be heard and taken seriously. Today, I speak to university classes and other places about my experience as a murder victim family member. I want people to put names and faces to the statistics they read. I want people to know how to respond when someone loses a loved one to traumatic violence.

And if you’ve ever wondered about how executions impact the prison employees who carry them out, read the 2021 reporting in The State by Chiara Eisner for an education on that.

While South Carolina has not performed an execution since 2011, the S.C. Supreme Court heard oral arguments this month and is expected to rule soon on which methods can be used when and if executions resume — lethal injection, firing squad or the electric chair.

For me, news of any execution — like the recent one in Alabama — is triggering. But I want people to learn what happens to co-victims of murder after the news stories stop. My mission is to widen the lens on what life is like going forward for people like me, to remove the taboo of speaking about murder to co-victims and equip people with ideas and insight on how to be truly helpful and supportive. I want people to know what’s helpful to say and do and what’s not. Taking the needs of co-victims seriously is long overdue. There are more than 28 million of us in the U.S.

I also speak about the death penalty and why I am against it. It is the last thing that victim family members need. First, the death penalty retraumatizes victim families. The months prior to the executions of my sister’s murderers were filled with relentless news coverage. We relived the horrific details over and over.

The law’s due process did not consider how the executions would impact me or my family. We were re-injured by this experience. There was no victim assistance at the time. My message: The death penalty doesn’t just traumatize the victim.

Sherrerd Hartness lives in Columbia.