Montana researchers say quick wildfire suppression leads to larger, more intense fires

The Big Knife Fire outside of Arlee, Montana, on the afternoon of Sunday, July 30, 2023. (Photo by Nicole Girten, Daily Montanan)

Research published this week by scientists in Montana is the latest to show that century-old policies to suppress wildfires as quickly as possible is contributing to more severe and larger wildfires over time.

The study, published Monday in the journal Nature Communications, looks at what the researchers call “suppression bias.”

The scientists identify “suppression bias” as the consequence of knocking down low- and moderate-intensity fires: Other fires largely burn hotter and scorch broader areas of forest and land, and people experience more of the most destructive fires.

“Over a human lifespan, the modeled impacts of the suppression bias outweigh those from fuel accumulation or climate change alone. This suggests that suppression may exert a significant and underappreciated influence on patterns of fire globally,” lead author Mark Kreider, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montana, said in a statement. “By attempting to suppress all fires, we are bringing a more severe future to the present.”

On the other hand, the researchers said less suppression of lower-intensity fires might make firefighting easier in the future.

Kreider authored the paper along with four other UM researchers and professors and an ecologist with the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute in Missoula.

They compare suppression bias when it comes to fire management to doctors overprescribing antibiotics: “In our attempt to eliminate all fires, we have only eliminated the less intense fires (that may best align with management objectives such as fuel reductions) and instead selected for primarily the most extreme events (suppression bias) and created higher fuel loads and more ‘suppression-resistant’ fires.”

The U.S. Forest Service estimates that 98% of wildfires are fully suppressed before they reach 100 acres in size – most of them within 72 hours. In Montana, fire managers strive to put wildfires out as quickly as possible; Gov. Greg Gianforte said last year that crews kept 95% of wildfires in Montana to 10 acres or less in 2022.

A water scooper drops water on the Colt Fire in late July. (Photo courtesy Colt Fire Incident Management/Inciweb)

Since the late 1800s and early 1900s, fire management policies have largely focused on protecting timber and homes from burning.

Montana’s state fire policy, adopted in 2007, states that minimizing property and resource loss from wildfires is the priority in fighting wildfires and is “generally accomplished through an aggressive and rapid initial attack effort.”

The policy also says that forest management including thinning and prescribed burns improves forests and that inadequate land management practices to reduce wildfire risk in the wildland-urban interface could jeopardize Montanans’ right under the state constitution to a clean and healthful environment.

But as more development, particularly in the West, encroaches on the wildland-urban interface, a century of fire suppression and climate change have ballooned federal wildfire suppression costs from hundreds of millions of dollars a year in the 1990s to an average of $2.8 billion a year from 2018-2022, according to National Interagency Fire Center data.

The total acreage burned each year has also doubled, on average, from what burned in the mid-1980s, and traditional fire seasons have increased by a month in length, according to federal fire managers.

But the new research suggests that reducing suppression for low-intensity fires and allowing them to burn when conditions are good could mean that fire managers wouldn’t have to work as hard battling extreme fires in the future.

“Through regressive fire suppression, we are effectively bringing a more severe future to the present—experiencing average fire severities that would not otherwise happen for a century,” the researchers wrote. “Our findings suggest that the abnormally high proportions of high-severity fire witnessed in many areas globally is due, in part, to the influence of the suppression itself.”

Models simulate fires based on suppression actions

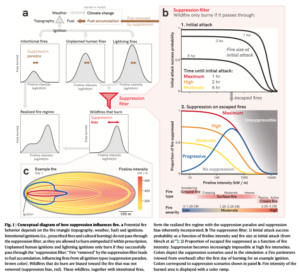

Conceptual diagram of how suppression influences fire. (Graphic via Kreider, M.R., Higuera, P.E., Parks, S.A. et al. Fire suppression makes wildfires more severe and accentuates impacts of climate change and fuel accumulation. Nat Commun 15, 2412 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46702-0)

The researchers built computer models that simulated thousands of wildfires under the same environmental conditions, but with different suppression responses. Those included three “regressive” scenarios of moderate, high, and maximum suppression; one “progressive” suppression scenario in which more intense fires were suppressed instead of lower-intensity fires and without an initial attack; and a control scenario in which fires were not suppressed at all.

They then used those models to figure out the proportion of fuels burned at both high and average severity, the size of the fires by day and for the entire event, and how severe or not each fire burned throughout its life.

The researchers also ran simulations accounting for a variety of fuel moisture levels and fuel amounts to figure out how different types of suppression affects fires in comparison to climate change and the build-up of dry fuels in forests.

Research shows maximum suppression leads to more severe fires long-term

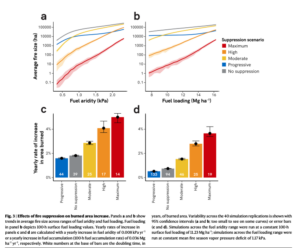

The maximum suppression scenarios modeled fires that had twice the proportion of each fire burn at high severity than fires modeled under the no-suppression scenario. The researchers said the increase in severity for maximum suppression scenarios compared to no-suppression scenarios was equal to the effects of 102 years of increasingly dry and built-up fuels caused by climate change.

Under the “progressive” suppression scenario, less of the fires burned at high severity, and the overall severity of the modeled fires was also lower than other scenarios.

How fire managers decide to attack fires could also have broad effects on the number of acres that fires burn when accounting for the effects of climate change, the researchers wrote.

Under maximum suppression scenarios, the annual area burned doubled every 14 years versus every 39 years under no-suppression scenarios when accounting for increasingly dry fuels in the future. The progressive suppression scenarios did not show doubling of the area burned until every 44 years, in comparison, signaling that scenario was better in keeping fire sizes down than even the no-suppression scenario.

Effects of fire suppression on urned area increase. (Graphic via Kreider, M.R., Higuera, P.E., Parks, S.A. et al. Fire suppression makes wildfires more severe and accentuates impacts of climate change and fuel accumulation. Nat Commun 15, 2412 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46702-0)

Progressive suppression scenarios also showed the fires burned more evenly than fires under the other scenarios, as well as a vast reduction in large fires compared to the maximum suppression scenarios.

“Though regressive suppression keeps many fires at small sizes and reduces the absolute amount of burned area (relative to a world with no suppression), in the face of climate change and fuel accumulation, it counter-intuitively leads to a higher relative rate of increasing area burned over time,” the researchers wrote. “…In our simulations, fires under the progressive suppression scenario had equivalent fire severity to unsuppressed fires burning under less fire-conducive conditions—in other words, effectively reversing the impacts of climate change or fuel accumulation by one to nearly two decades.”

They said the longstanding efforts to minimize all types of fire have “likely shifted the selective pressures of natural selection,” leading to decreased diversity of species after fires and increasing invasive species.

“I wonder how much we are altering natural selection with fire suppression by exposing plants and animals to relatively less low-severity fire and relatively more high-severity fire,” said Andrew Larson, a professor of forest ecology at the university and Kreider’s adviser.

Researchers’ goal to inform firefighting policymaking

The group said its purpose in the report was to look more into suppression bias and how it could improve the understanding of fires and how humans interact with them – especially in a world affected by climate change.

“A society living under progressive suppression would be less stressed by climate change, as their perceived ‘normal’ conditions would change half as fast,” the authors wrote. “By allowing more lower-intensity fire, progressive suppression could buy time, helping societies and ecosystems adapt to climate change.”

But changing the manner in which national, state and local agencies respond to different types of wildfires will carry challenges, the researchers said. Those agencies have long-ingrained policies focused toward regressive suppression, and the public might not trust a progressive approach after so many decades of seeing agencies try to put fires out as quickly as possible.

A firefighter uses a drip torch during firing operation west of Rainy Lake, Friday, July 28. (Photo courtesy Colt Fire Incident Management)

Further, they wrote, only focusing on attacking high-intensity fires is not always practical or safe, and agencies prioritize firefighter and human safety above everything else.

The encroachment further into the wildland-urban interface also presents challenges, as another top priority in Montana and other states is minimizing property loss from wildfires. And smoke from lower-intensity fires that burn for longer and an increase in prescribed burns could lead to increased smoke-related health effects, which the researchers say would need to be addressed by public health interventions.

The researchers said that where feasible, however, fire managers should consider moving from maximum suppression efforts to lesser efforts on the lower-intensity fires to reduce the suppression bias. That also includes putting more prescribed fires and cultural burning — typically done by Native American tribes — on the landscape in conjunction with more progressive suppression tactics.

“Such fire management could implement regressive suppression approaches when necessary (e.g. near human infrastructure) and progressive or no suppression approaches when and where more feasible,” the report says.

Last year, federal agencies updated the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy to include more prescribed burns and more fuels treatments in their strategies to reduce the risk of wildfires and to better account for climate change when modeling future forecasts and predictions.

Philip Higuera, a co-author of the paper and a professor of fire ecology at UM, said it may seem counterintuitive, but the research shows that accepting more wildfires should burn when it is safe should be the main takeaway.

“That’s as important as fuels reduction and addressing global warming,” he said.

The post Montana researchers say quick wildfire suppression leads to larger, more intense fires appeared first on Daily Montanan.